By Paul Falardeau (Contributor) – Email

Print Edition: November 30, 2011

The lighting in the Centre for Indo-Canadian Studies (CICS) was dim on Wednesday evening, November 23. Flickering candles gave a surreal mood to the room, and cushions and sheets were arranged on the floor for seating. The occasion was a first-ever for UFV: a performance by virtuosic Indian classical musicians, Pandit Manu Kumar Seen and Ustad Akram Khan.

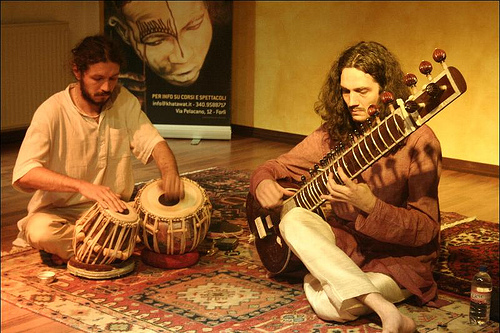

Hosted by The CICS in association with the Virasat Foundation, the concert, scheduled to run from 7-9 p.m. featured Seen on Sitar and Khan on Tabla. Both men are from the Northern Punjab reason with Seen making his first appearance Canadian appearance in Vancouver in 2002.

After some warm-ups and a brief introduction by event organizer and CICS director Satwinder Bains the duo started the first of two sets, an instructional lecture and demonstration. Each performer explained some of the basic points of his instrument and, although the hour-long demonstration only hit the tip of the iceberg, the complex nature and requisite skill needed to play both instruments became immediately evident.

Khan remembered how boring it was as a thirteen-year-old boy, playing a single composition over and over again to learn tabla “but we never questioned [the Guru].” Still, he affirmed that it was through this repetitive, disciplined practice that he was able to master his craft. He still regularly plays that first composition.

Ever calm and always speaking in humble tones, Pandit (a similar title to Italian “maestro”) Seen explained that he feels “music is a universal language because there are no words, only songs. Words have no meaning in them inherently; it is based on sound that we find meaning.”

On this note he explained all the different sounds available to the classic sitarist and Khan did the same for Tabla. After this tutorial the audience of about 50 was treated to coffee, tea, samosas and other treats.

They returned to play a full mini concert that ran well past the 9 p.m. end time. Yet the audience, captivated by the duo’s sound, did not seem to notice while in the meditative state the music encouraged. Seen explained that different ragas (scales) are meant for different seasons, times of day and moods and that some, mostly devotional in nature, are fine to play any time. With this is mind the evening started off with a raga intended for the rainy season, but also delved into songs for evening, songs of marriage and everything in between.

The fact that Indian classical music is obviously tied to the place of its creation is reflected in the specific times different pieces and meant to be played, but also by the instruments sound. Ragas morph from languid, sweaty reverberation to blistering finger runs where the players’ hands become a blur over the fret board and skins of their respective instrument.

One idea repeated throughout the night was the importance of “preserving the rich culture of India.” The intersection of western and eastern views of these instruments was an interesting and easily-accomplished goal. Many westerners still see the sitar as exotic and usually as part of the psychedelic sound where it was first introduced. Pioneers like Brian Jones and George Harrison opened the world of Indian classical music to the average western music fan. Harrison, himself, was a student of the legendary Ravi Shankar and instrumental in Shankar playing at the first Monterey Pop Festival.

Still, with the Sitar dating back at least to the time of the Mughal Empire, it can be held in a different light entirely by people of South Asian descent. Classically, as the events name implies, the way the west would hold Mozart or Vivaldi or simply as a quintessential piece of Indian culture, as inseparable as the guitar in modern western music. This, as much as the Beatles or Ravi Shankar is a part of the “rich culture of India” and through events such as this one, should preserved—and revered—for ages to come.