By Karen Aney (The Cascade) – Email

Print Edition: February 29, 2012

Organic foods are an increasingly popular nutritional focus. Here in British Columbia, we may have a higher exposure to them: according to the last available statistic from Statistics Canada, though British Columbia accounts for just 13 per cent of Canada’s population, it also accounts for 26 per cent of organic food purchases made in Canada. However, there are some important things to understand about organic food that aren’t yet widely known facts.

Organic foods are an increasingly popular nutritional focus. Here in British Columbia, we may have a higher exposure to them: according to the last available statistic from Statistics Canada, though British Columbia accounts for just 13 per cent of Canada’s population, it also accounts for 26 per cent of organic food purchases made in Canada. However, there are some important things to understand about organic food that aren’t yet widely known facts.

First and foremost, it’s important to note that the above statistics, and any others in this article, refer to certified organic foods. In order for a food to be certified organic, it needs to be produced on a farm that has been certified as such by the agriculture faction of the government, or an entity entrusted with certification by said faction. This means that a farm must follow all organic practices for an extended period of time, then hire an individual to perform an audit stating those practices are being adhered to completely. This is a costly process: if a field has, in the past, had pesticides used on it, it must aerate for an extended period of time until the pesticides are no longer detectable. Though there is no specified length of time, it can take multiple years. Aside from the aeration process, the act of certification itself is costly. In order to become certified, a government employee—or a contractor hired by the government—must visit the farm to perform an audit. Given the varied size of farms, this can take multiple auditors and multiple days. Because they’re government employees, they’re well compensated: one local farmer stated that he was required to pay the auditor between $45 and $50 per hour.

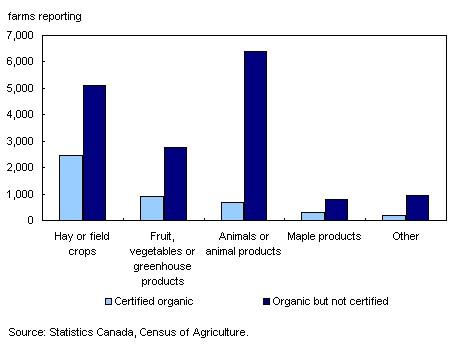

Because of the costly and difficult process that certification entails many farms that may adhere to organic practices and standards may not necessarily become certified. This is demonstrated in the graph to the right, care of Statistics Canada. Animals or animal products clearly represent the largest discrepancy, with close to 6000 farms following organic practices but not certified as such.

The largest amount of organic product produced in Canada, by far, is grain. The Canadian Wheat Board states that over 71,000 tonnes of wheat, barley and durum was produced in 2005. However, this industry is indicative of a problem with the production of organic foods in general. Though 71,000 tones are produced, only 16.7 per cent of that is sold in Canada. The remainder is exported, at great environmental cost. Though this provides Canada with a strong component for its agricultural industry, it also demonstrates that many certified organic farms in Canada are predominately, if not exclusively, export based. The added cost of achieving certification is far more attainable for those farms that are able to export their goods. Further, certification is a necessity in order to market your food as organic in other countries, and is closely regulated.

Why eat organic?

The answer to that question is somewhat hazy. Many studies conducted on organic food demonstrate the heightened health benefits and reduced risk from pesticides and processing methods. They also depict the benefits that organic farming can have on the environment.

One such report from Greenpeace found that organic growing methods produced higher yields. This report was based on findings from the Southern hemisphere in predominately impoverished nations. In Ethiopia, chemical-free farms produced three to five times as much produce. In Brazil, maize crops grew from between 20-250 per cent. Particularly in areas of greater need, this presents a wonderful tool. However, the principles found in this report can—and are—also applied to farming in Canada, which results in higher production of goods for export and a more affluent nation overall.

Numerous blind studies conducted by non-industry experts (translation: everyday people) also suggest that organic food tastes better. One such study was done by the Washington State University. They reported that “the organic apples were firmer, tasted sweeter, and were less tart” than inorganically grown apples. The study went on to reaffirm what Greenpeace reported – further than having a more desirable taste, the farms at which the organic apples were grown reported higher yields than those that didn’t.

Many studies do find that organic food is healthier. Some report lower risk of breast cancer – pesticides are known as a carcinogen. Another study conducted at Glasgow University found that store-bought organic soup had up to six times as much salicylic acid compared to non-organic store-bought soup. Salicylic acid has many positive effects: it fights bowel cancer and prevents hardening in the arteries. It also serves as a natural remedy to stress. So the higher-priced organic food may be better for you than the regular stuff.

However, there is no conclusive scientific evidence stating unequivocally that organic food is better for us than non-organic food. The Scottish soup study could simply be a case of healthier ingredients in the organic products, for instance. A great study to look at if you’d like to see the conflicting findings is “A Comparison of the Nutritional Value, Sensory Qualities, and Food Safety of Organically and Conventionally Produced Foods,” published by Diane Bourn and John Prescott. This piece synthesizes the results of other studies and points out flaws in their process or findings. Their conclusion, as stated in their abstract, is revealing: “With the possible exception of nitrate content, there is no strong evidence that organic and conventional foods differ in concentrations of various nutrients.” Nitrate content alludes to pesticide residue. So, according to this study—and corroborated with the conflicting reports found in the media each day—there’s really no way to know for sure yet if organic food is truly better for us.

Making the choice to eat organic is difficult with so much conflicting information. The best practice is to carefully read the labels of all the food you’re eating: where is it produced? Where is it processed? What does it contain, and which additives? If you’re looking to eat healthier food, yet you aren’t sure about the certified organic practices, try looking in your own back yard.

Check out next week’s issue for part two of our coverage of organic eating.