By Michael Scoular (The Cascade) – Email

Print Edition: May 7, 2014

David Gordon Green has been linked to a kind of poetic realism — there isn’t much of it in American cinema, and he cuts to osmotic riverbeds, animals resting in the tall grass that seems to surround most of his pictures, and tree outlines sometimes, so why not? But by now, nine(!) films in, it’s apparent that Green isn’t a descendent of Terrence Malick — it’s closer to say Malick is a friend, and Green’s filmmaking method is one that comes out of tying work to creative friendship, high school-level humour, and an appreciation for natural beauty, which shows up in sometimes odd, sometimes paint-by-numbers ways.

Green strives to make movies, not necessarily an elusive great movie, and along the way has disproved a lot of attempts to set him on a creative path (not simply a regional filmmaker, not a painter with light, not a sensitive dramatist).

“Not good,” some critics said, pegging his track record in disarray when he took his lazy, loose sense of conversation (a thin line between that and the Apatow improv floor) to Hollywood, but despite the way it’s easy to pick and choose the similarities that could grant him the status of a minor auteur, his guiding principle is less the cinema than it is the set — Joe, his latest, is his first since Snow Angels to be based around performances that transform after the word “action!” in a more classical sense. His directorial influence is most noticeable in his casting choices, and the way he guides his often untrained or young actors in ways that reveal an inner idiosyncracy — the language that makes George Washington and All the Real Girls still memorable, but also what allows the diner conversation that ends Pineapple Express to unspool, as actors, who hardly need character names at that point, talk about their favorite parts of the movie they’ve just been in.

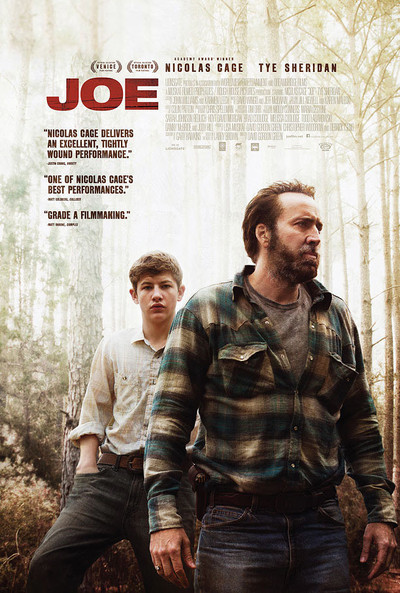

Joe is locked into character in a different way. From the moment Nicolas Cage enters the frame, hooded, rain-pelted, managing a forest crew with a “round ‘em up!” the film is set to his pace, which he alters to a near-shamble. He isn’t spry, he’s an alcoholic, and he directs a group of non-union workers in an ersatz version of lumberwork: their job is to funnel poison with hatchet whacks into an area construction projects want treeless. Cage, wearing tattoos and and letting out exhaustion at the end of each shift, is their trust. Joe is their paycheque, but also a leader by charisma, which grows in meaning when a half-beaten, runaway-headed boy named Gary (Tye Sheridan) asks him for a job.

Green, since his trio of studio comedies, has moved back to Austin, Texas, and Joe’s relation to the local film industry is prominent. Sheridan, after his debut performance in Malick’s The Tree of Life, was cast in Jeff Nichols’ Mud, and in Joe he plays a variant of that movie’s protagonist: his father (Gary Poulter, one of Green’s non-professional cast, in a singular, discomforting performance) hates and uses him, and so he draws near to someone who can be a different, more respectable model. Green is able to make a much better film than Nichols did, even with some of the same ingredients. The first day Gary works on the job, Green, with regular cinematographer Tim Orr, manages to connect the natural close-ups and broader human characters that have often existed on other sides of a partition in his work. David Wingo’s score hums and draws the meditative work that briefly contents the two main characters in succinct contrast with the rest of the film’s complicated relations.

It’s easy to guess that Green’s film is adapted from a novel. Neigbouring characters show up for single, sharply-drawn scenes; main ones cycle through routines; and the film’s pace is deliberately not drawn tight (we see Cage fall asleep to television, and Sheridan walk to and from work). Some of the film’s supporting performances (Austin theatre actor Adriene Mishler as Connie, putting up with Joe’s “I like you too, but what’s the point in any of it”) are given almost, but not quite enough time to live within each character’s memories, which Green seems to be after. Joe’s turmoil, which Cage displays without ever turning into caricature, is entirely about personal histories, and how he sees Gary’s being written for him. Larry Brown’s book by the same name is related in a sense to the southern gothic tradition, and there are parallels within Green’s own work: his remake of Charles Laughton’s The Night of the Hunter, Undertow, was a rust and pocked earth excursion into inheritance and bloodshed. It also paled next to its predecessor.

With Joe, Green has not made the perfection of an artistic vision, but continues his work as a director who crosses over between television and film, studio and location, perhaps “less than meets the eye,” but convivial, agreeable, and not about to make a swing for prestige.