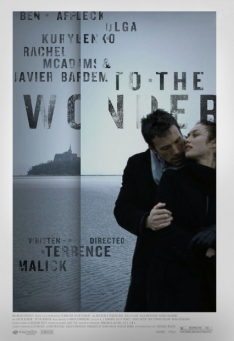

By Michael Scoular (The Cascade) – Email

Print Edition: May 8, 2013

Terrence Malick’s movies, though all previously period pieces, have done anything but avoided present time. It’s there in the way his images of violence, the pastoral, wars, romance and home amid the universe are only possibly past – to put them in a current frame is to risk derision or the label of incommunicable. They exist within the danger of the slippage of time, yet attempt to reach that presence.

Terrence Malick’s movies, though all previously period pieces, have done anything but avoided present time. It’s there in the way his images of violence, the pastoral, wars, romance and home amid the universe are only possibly past – to put them in a current frame is to risk derision or the label of incommunicable. They exist within the danger of the slippage of time, yet attempt to reach that presence.

Maybe the best example would be the dividing point of WWII in The Thin Red Line, where the human force within nature, the point of compassion, and the barriers of communication: phones, language, letters and openness to the natural, graspable wonder that is right there, present, intertwined in elevated, polyphonic verse. What To the Wonder does is place this same reaching beyond—Malick’s questions and invocations of beauty—in the obviously present day, locked into the spaces his images typically seem to try to escape.

Malick’s sudden, late prolific pace means there is for the first time consistency within his work. The marked differences between Badlands and Days of Heaven and The Thin Red Line, and even from there to The New World and then The Tree of Life is not the case here. In editing rhythms, camera movement and occasional use of music, To the Wonder is akin to The Tree of Life to the point of predictability. Magic hour unmatched cuts from a camera alive with spontaneity, capturing brief burnished glows before swiveling toward the movement of the wind, nature and balancing dancing bodies is in itself no longer as spontaneous as it was at first sight. But this is part of what Malick is doing, and while it may not be entirely successful, what sets this apart from the rest of his work is how his images, in method full of beauty, in effect cannot change the unimpressive, undesirable conflict at the movie’s core: a cowardly, posturing archetype of masculinity (Ben Affleck) and an idealized, in-motion giver of beauty and light (Olga Kurylenko).

This, too, resembles The Tree of Life, with some snatches calling back memories of that piece (a wide shot of assembled kickball, parental arguments heard filtered through floors and walls). But there is none of the fixed, restoration by recall of Malick’s last work. To the Wonder is completely of the present, with cellphone video, Skype conversations and modern conventional architecture all markers of mediated, alienated living – one unvoiced question might be if an existence like in the Tree of Life’s could possibly last here. But this is not simply nostalgia: in Malick both the personal and general questions constantly issuing hold spiritual purpose.

Christianity informs Malick’s films, but there is more than a direct message-to-verse reading at work here. While deprivation of joy correlates with depiction of mundane suburban neighbourhood grocery store gas station living (the same grandiose camera and score, but turned from the skies to pavement), what gains more focus in To the Wonder is the uncomplementary interpersonal relationship that undergirds everything. As understood from the teachings of the church (represented in the film by Javier Bardem’s character of a priest), this has its roots in disparity of belief. Affleck in voiceover recognizes and fears rifts that would be caused by knowledge of his weakness of faith, and dissolution between him and Kurylenko can be seen to come from that. Her attempts at spontaneous response, laughter and freedom of movement are met with immobile stances returning to the mean of domesticity, in contrast to the romantic poetry of the film’s Paris-set opening. For as in all Malick’s multi-voiced works, these are freely given voices, not an endorsement of each, and the confirmation of religion’s labels (Bardem, as well, is in a constant state of doubt) is only a result that comes from the underlying tension and causes Malick enters into.

Some of the To the Wonder’s more interesting irresolvable qualities, but also its simplest, weakest moments, come from this critical approach to Affleck’s performance. It is not blank, because it portrays a recognizably reticent and controlled kind of male role, reaching near-metaphorical imagery in favoured stances of hands-on-hips and a deliberate long gait, oppositional to his balletic claimed-beloved. Divided by language (he replies in English to her French) and defined by repetition rather than variation, he is numbness surrounded by impermanence, and yet conscious of this, though not enough to lead to visible difference – Malick’s concept of love is inexplicable and unchanging. Located in one of the movie’s more obvious parallels—the work of the two main male figures, conflicted and partially rejected—is a question like one posed in The Thin Red Line: “Do we benefit [our surroundings]?”

Those surroundings are pitched at a lower level than The Tree of Life’s – there is no strong suggestion of an afterlife, and even the scene of a prayer shows only those immediately around. Though Malick always contains a spiritual throughline, To the Wonder makes central that how he arrives there is purely material: Malick’s two most defining aesthetic marks most closely resemble partially eavesdropped conversations passed by and a restless eye searching for beauty, neither the mark of the eternal or expansive.

A piece in New York Magazine by Bilge Ebiri catalogued Malick’s methods for providing character inspiration to the cast of To the Wonder, many coming from classic Russian literature. The actual film is set in modern Oklahoma, and has at least a passing interest in the way of life specific to the area. These dissonances partly comprise To the Wonder’s compilation: shots, feelings, the seemingly contradictory forces of secular affair and spiritual romance, literary classic and present day, the search for beyond interior and what is a story easily found.

Perhaps Malick has only complicated and beatified a universal and relatively conventional narrative, one arguably already better done by filmmakers both past and present (Eric Rohmer and James Gray, to name two). But Malick’s films have the distinction of how they grow and fade over time, forgotten shots becoming significantly different from first impression, dialogue changing from esoteric to immediately understood. This does not excuse some of the misjudgments present, but in this attempting, To the Wonder is a film attuned to the process of romantic thought, which can work by turns ridiculous and religious.