By Michael Scoular (The Cascade)– Email

Print Edition: September 11, 2013

Every year, student journalists from most of the college and university papers in Canada meet at a conference. There are speakers throughout the day (journalism and marketing types), the chance to meet and exchange ideas with people with similar interests (which can be both good and bad), and each day ends with a relatively high-profile keynote on some aspect of writing and communication.

As a final impatient address before the main keynote attraction, two representatives ran through a list of “ways to avoid racist language.”

These were rules anyone would know, if only by repetition in middle and high school assemblies – or, you know, using common sense. Why was a collection of people usually known for left-wing publications that latch onto issues of race, gender, and class for many of their political statements being told this? And why was the response near-unanimous applause? Instead of its intended message, the address both reminded of the occasional blindness that these topics are often broached with by seemingly intelligent people, and undermined the credibility of everyone involved.

Either the address was unnecessary, since the theoretically non-racist university student doesn’t need a mini-lecture, or it was necessary, and people need reminders to guard against their racism with language that hides their usual inclinations – a reminder not to slip at an official event.

While even enthusiastic applause can be written off as required courtesy, their response was a contentedness with knowledge of politically correct language, rather than the difficult vulnerabilities of confronting the internal inconsistencies of—if we don’t want to say prejudice—where we place emphasis in the stories we tell.

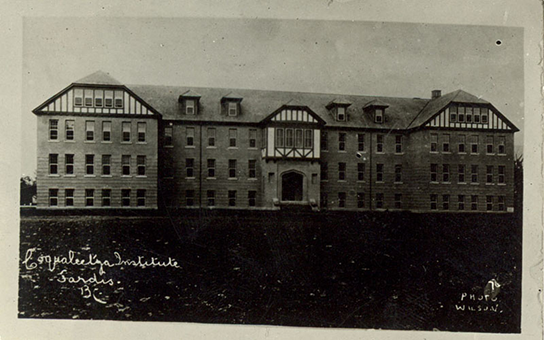

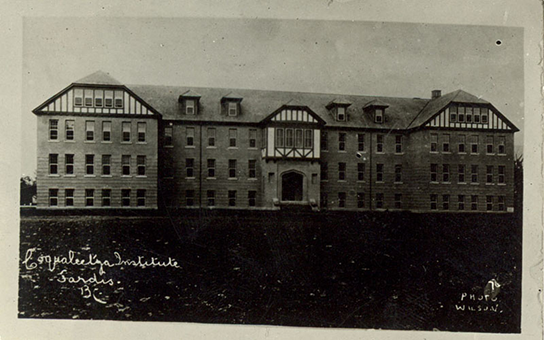

I can only guess this same reasoning is behind the Indian Residential School Day of Learning. There is the chance that many students, some of them just out of high school, are unaware of the part of history the day hopes to open up.

The Day of Learning will offer a course of new accounts, evidence, and thoughts of the imbalance of power and capacity for cruelty to any student that attends. Giving a platform to speakers split between a voice that will go unlistened to and one that has been imposed is an uncommon subject for schoolwide attention.

But in a way this is nothing new. The people who will go to the event (the lack of classes making this even more of a personal decision) will not make the choice in a vacuum.

Regardless of who chooses to attend, knowledge of the existence of residential schools has been absorbed by many through the past decade of apology attempts and offerings of financial amends. These are not finalizations of history, and the media portrayals of these high-profile days cannot be counted on for the nuance of a personal speaker, but the importance placed on a day for an education covering years and lives is awfully close to the idea of learning about the world through issue-based documentaries.

Should the event be well-attended, there is nothing to stop it from being no more than a temporary jolt to complacent thinking that’s overridden by the immediate resumption of schedules.

And what happens after? Will there be any more days to remind of how Canada’s benevolent tolerance is as much an advertising style as it is a reality in practice? One for the Ukrainian and Japanese internment camps, or the Chinese head tax, or is Remembrance Day patriotism considered enough remembering for a year?

Students, the hope goes, will be inspired to act. But how this Day of Learning reaches—or cannot reach—students will rest on more fundamental questions than how a complicated event comes to be organized, or what can be done to achieve understanding and harmony between cultures divided by murderous histories and racial differences. Is it a change in the way people think or only the words they use education will try to affect? Do we want to be thought leaders, counting on one response to our words and actions? And once the facts are known, is the difference further education makes only the level of sophistication used to describe the same position?

The Day of Learning’s mandate is to expose racial oppression and cultural homogenization in an unavoidable way to attendees, but anyone living with open eyes, even if they don’t know the specifics, has already witnessed this and reacted.