By Nick Ubels (The Cascade) – Email

Print Edition: March 20, 2013

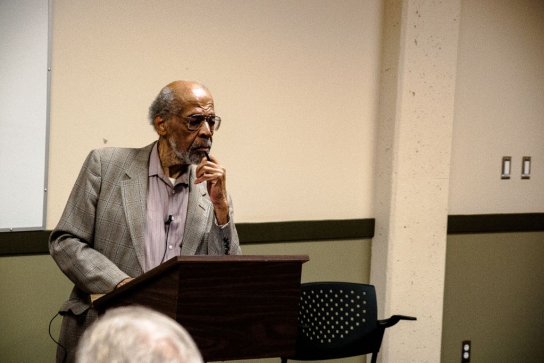

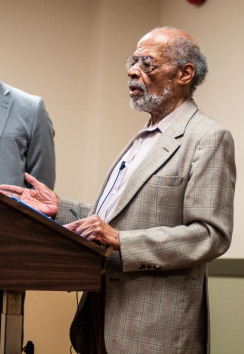

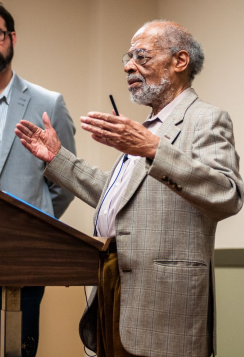

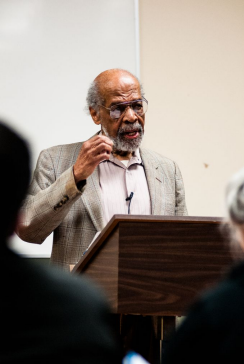

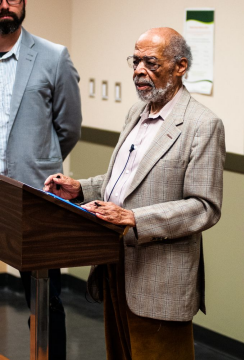

After a lifetime of service in some of the most vital social movements of the 20th century, Jack O’Dell says that there is still “unfinished business” in the cause of human equality and freedom.

Born in Detroit in 1923, Hunter Pitts “Jack” O’Dell spent over 47 years actively advancing the cause of social justice, civil rights and peace in his home country of the United States and around the world.

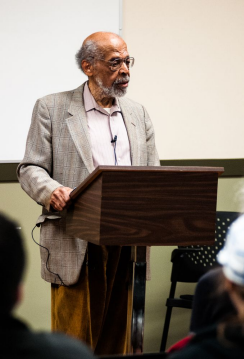

A crowd of roughly 50 students, professors and community members, including one grey-haired man proudly sporting a merchant marines baseball cap, gathered at UFV’s Abbotsford campus last Thursday to listen to O’Dell speak about his experience in the civil rights movement and its relevance today.

“You do what is possible,” he said. “Usually, you can generate enough to keep on steppin’.”

In decades following the second world war, O’Dell was a member of the merchant marines, the National Maritime Union and the Communist Party before joining Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) as a director of voter registration and fundraising.

He spoke eloquently about Dr. King’s legacy, disdain for accolades and fundamental message of peace.

“He understood what the meaning of life is,” O’Dell said. “We are all a part of the human family.”

O’Dell eventually decided to leave the SCLC in 1963 after external pressure from Democrats who feared associating with one-time Communist Party members. This opened up the opportunity for O’Dell to write for Freedomways magazine, one of the black freedom movement’s leading journals. In his 21 years as associate editor, he wrote dozens of editorials and in-depth essays addressing the most pressing issues in the civil rights movement during those turbulent decades following Dr. King’s assassination.

After 40 minutes behind the podium, the 89-year-old activist turned the tables, opening the floor to the audience for what was a robust and open forum about how to tackle the important social justice issues of the 21st century. It was here that O’Dell seemed to take most interest, taking detailed notes on comments from students and answering with vigour to match a man half his age. He was visibly energized by the lively discussion.

O’Dell fielded questions about the national treasury, affirmative action, slacktivism and veteran’s rights during the meeting.

He criticized the use of unmanned drone attacks and the treatment of returning soldiers in the United States, where more troops have died from suicide at home than in the battlefield over the last six months.

“Justice and peace are indivisible,” O’Dell said.

In the final stage of O’Dell’s 47-year career in the United States, his focus shifted outward, to the cause of international peace in places like South Africa during the struggle to end apartheid. He was also the director of Pacifica public radio network, a senior adviser in Jesse Jackson’s two presidential campaigns during the 1980s and a member of the PUSH/Rainbow Coalition, which concerned itself with addressing inequality and racism internationally.

“Our place,” O’Dell said, “is to assist our respective countries to become the standards of rights, privileges and national morality that can moved toward a different age in history in which we recognize each other as brothers and sisters and we save our planet Earth from the destruction a negative attitude will surely bring.”

“That’s what’s at stake. And I’m sure we’re going to do all right.”

I spoke with Jack O’Dell over the phone early last week about the legacy and enduring lessons of the twentieth century civil rights movement.

What do you see as the most pressing issues of the present moment in terms of social justice and peace in Canada and abroad? What deserves our most attention right now?

Essentially, we need to address the money we spend on war. Dr. King already laid that out in the Riverside Church speech. The point is that year after year, spending more on war than social programs is a country approaching spiritual death. We don’t live by killing people, as a society I mean.

So that is the vision that we are trying to institutionalize in the country as a whole and in the movement: that war and violence and poverty are not things that people should be forced to live with.

These are not natural functions of our existence. We’re not naturally at war with one another or naturally poor. Wait, no. Not in the midst of all this wealth we have. It is this reformation that we seek. And the inequality and the fact that people think they’re going to the armed forces because it’s a job. Some people just sign up because they need work and there’s no work back home.

Now wait a minute. That won’t stand. You can’t have a society worthy of the name called democracy as long as those are the priorities. We need to have other priorities that make us more human, more democratic, more of a community. The world is our community. You can’t even have community in your own country with distorted values. We have to kind of be looking at things the same way. And there’s no reason not to.

What are we going to pass on to the next generation? What would my generation pass on to your generation is we didn’t fight to improve life? And war and corporate greed and insulting people who have a different lifestyle or a different national identity, these are all impediments to a life of democratic rights and reasonable happiness for everybody.

In your life as a civil rights, social justice and peace activist, you’ve taken on a really wide range of leadership roles in different organizations. How would you characterize the diversity of your experiences and involvement in different movements over the years?

In your life as a civil rights, social justice and peace activist, you’ve taken on a really wide range of leadership roles in different organizations. How would you characterize the diversity of your experiences and involvement in different movements over the years?

I would characterize it as a sampling of life. Life is diverse. Diversity is one of the characteristics of nature itself. If one is involved in a movement that reaches out and it is all-encompassing, like our movement was, it’s likely that you will have a variety of experience with different segments of the population, different ideas and different institutional frameworks.

And all of that, of course, is very valuable for us as human beings.

What was it like the first time you saw Dr. King speak?

I was working in the insurance business in Birmingham and a bunch of us got in a car and went down to Tuskeegee. He was invited to speak there because the Tuskeegee movement was facing a situation where the black vote had grown in strength and the city council had voted to move the black community out— in terms of the gerrymandering of the districts—of Tuskeegee proper and put them in the rural area so that they couldn’t elect somebody to the city council. That was the issue.

And so what I was impressed with was this. When he got up he said, “You know, I’m here to support you, but you already have leadership here. You have a leadership here that’s worthy of your full support and we’ve all heard them here this evening. I’m not going to make a long speech because they’ve said all that needs to be said on this occasion. I’m very happy to be here. I support this movement 100 per cent, but trust this leadership. And this is what we have to do all over the south: we have to build local leadership.”

That was an act of common sense, but also of great leadership character. He said, “I know you all came to hear me, but I want you to reflect on the quality of leadership you have here.”

That’s what he saw as the remedy in terms of building a grassroots movement. And he was right.

What was your experience at Freedomways like?

Speaking personally, it was one of the best things that ever happened to me. Because I would not have found the time to do the writing that I did.

The writings last, you know what I mean? Some other things are forgotten, but if something is published in a magazine – Freedomways was published in 1500 libraries across the world and libraries had bound volumes in England and Wales and France so I said, “woah.”

It feels good to know that I had the opportunity to do some studying and do some writing and get it published because that is a contribution. If Freedomways had just been one of those magazines like JET magazine or something like that, I probably would have turned it down, but Freedomways was a magazine that was founded on the idea of completing the Second Reconstruction and Dr. W.E.B. Du Bois’ work. He was one of the inspirations for Freedomways magazine. I was very happy to do that and very lucky.

It’s interesting what you were saying about the writing enduring because I was recently reading through Climbin’ Jacob’s Ladder, which collects some of your essays from your time at Freedomways as well as some of your other writing. There was one phrase I wanted to ask you about from the title essay, first published in 1969 right after the death of Dr. King, where you wrote about the need for “revolutionary patience” in the cause of social justice. What did you mean by that? Is such patience still needed today?

It’s interesting what you were saying about the writing enduring because I was recently reading through Climbin’ Jacob’s Ladder, which collects some of your essays from your time at Freedomways as well as some of your other writing. There was one phrase I wanted to ask you about from the title essay, first published in 1969 right after the death of Dr. King, where you wrote about the need for “revolutionary patience” in the cause of social justice. What did you mean by that? Is such patience still needed today?

Social justice, in our societies here in the West, is an ongoing effort. Women have had to fight for their right to vote, Latinos for their right to live here as immigrants, labour for the right to organize. Social justice covers that wide range of effort that has been at the base of America ever since its founding, the right to be respected as a citizen and enjoy the rights of every other citizen.

My point was: it’s necessary to recognize that it’s a lifelong effort. Without the sacrifices many people have made, our movement would not go anywhere. Some people make a fine contribution and then they’re out of there. But some people have to make it a more or less lifelong activity.

Of course, I had travelled in the merchant marines and I had seen other countries, so I was not crazy about living in the United States. But I said if there was a movement to end segregation, I would give my time to it. And I found that movement and I stayed there 47 years.

Things that are important often don’t happen overnight. That is, they are the result of an investment of time, energy, thought. And also, you have to study what you’re trying to change, because it has a framework and a structure. It isn’t just changed by your energy. It’s about knowing how to dismantle it.

And that means you need to listen respectfully to the arguments and so forth and to recognize that we’re all human and that some of those people who are on the other side of the fence when you start will be on your side if you can establish a dialogue, if you can have the kind of attitude toward them that we should be talking, rather than contesting each other’s position.

None of us know everything. And there’s something to learn, even from the people who are on the opposite side from you. Why do they think that way? What in their life has brought them to that conclusion? All of that is in the process of growth and development of the individual and the movement because that’s what the movement is: a tide of individuals who have decided that change is necessary.

In 2005, you proposed a sort of democracy charter, which outlined some goals for social justice and there was a lot of big things on there that line up with Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s Second Bill of Rights, which he unsuccessfully tried to bring in and was intended to provide security and equality. Your charter includes universal health care, ending homelessness, restoration and protection of the environment and an accountable prison system among many other things. Eight years later, how much progress do you think has been made towards some of these big goals?

In 2005, you proposed a sort of democracy charter, which outlined some goals for social justice and there was a lot of big things on there that line up with Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s Second Bill of Rights, which he unsuccessfully tried to bring in and was intended to provide security and equality. Your charter includes universal health care, ending homelessness, restoration and protection of the environment and an accountable prison system among many other things. Eight years later, how much progress do you think has been made towards some of these big goals?

Very little. But these goals have not been on the agenda, really. It’s been on some people’s minds and some people on paper agree, but they have not been on the agenda of action in the same sense that other things have been. It’s in its early stages.

As you know from reading that, I got that idea from the Freedom Charter in South Africa, which they adopted in Kilptown in 1955. Well, it took them until 1990 to even start implementing any of that, and that’s 40 years.

The test of the value of a document like that is whether or not it addresses the changes that need to be made. Too often our movement is just working on one thing at a time, so to speak, and the perspective is limited because all we have on our agenda is getting rid of a particular thing. A more holistic viewpoint can sustain a movement to go from one thing to the next because it is probably the dismantling of a whole number of things and the creation of new things to replace it that constitutes what we’re really trying to do.

We’re trying to make America a truly democratic country, but the culture has not promoted that, because the culture is in the hands of the people who benefit from America the way it is. So change does take time, along with patience and thoughtfulness and recognizing that it may change a little bit at a time and then there’s a great change.

Like the 1960s saw a profound change. We’d been against segregation for a long time, since Plessy V. Ferguson in 1896. That doesn’t mean that all the other time was in a vacuum. No, people were working on it in the zig-zag or whatever until you get to that moment where it becomes irreversible and the change kicks in. Understanding that is part of the art of being able to survive. Otherwise you’re fraught with disappointment and it can cause you to break out of the ranks. Something is going to happen if you’re on the right course.

Testing the right course is how people receive what you’re saying. Some people receive it, but they don’t act upon it. You have to know they’ve heard you. You have to know how you say something, because you might have a good idea, but you got to learn how to express it to catch people’s imagination. That’s a learning process.

So the time is not wasted. It’s well-spent, but you have to understand that it will take time.

And that should be, not the reason to delay doing things, so to speak, but to understand that you have to build that understanding into your proposition. This will take some time.

And in the course of that time, what you’re proposing could get improved considerably.

I told the folks down in Oakland and a couple of other places that have been working on this democracy charter, “You need to test this. This is not in stone.” I put this out for the purpose of developing something that people will gather around like they did in South Africa. The Freedom Charter held the South African movement together over the period from the time where the people were locked up in the early 1950s. When we were there in the 1980s, with Jesse Jackson and our delegation, the Freedom Charter was the thing that was holding people together because that was a vision of the South Africa they wanted.

They knew what they were against, but the Freedom Charter was the vision of where they were going, where they were headed. And those two things are dialectical, aren’t they? It’s where you are now, but where you’re trying to go. That’s always the case.

That’s the role that I want the democracy charter to play for us. What is the America we seek?

And that isn’t just in little sections of, like, okay, I want such and such a thing. It is holistic. Everyone is looking at the country from the vantage point of their situation. So what do we see as common that we can unite around? And that’s the America we seek.

And so we seek a different America. Let’s be clear on that. If we don’t seek a different America, we’re in serious trouble because there’s a whole crowd in the United States that’s ready to take the country back because they’re profiting from it.

The one per cent, they’ve got a plan. We better have one, too.

That’s something I was going to ask about. The democracy charter outlines and articulates specific long-term goals. Do you think that’s something that the Occupy movement and other sort of social movements these days could benefit from having?

That’s something I was going to ask about. The democracy charter outlines and articulates specific long-term goals. Do you think that’s something that the Occupy movement and other sort of social movements these days could benefit from having?

They must have it. But take from that what they can use and substitute the rest. The point is you need to have a long-term vision because it’s going to take a long time.

If we get surprises and we accomplish something sooner than we planned, good! [Laughs] Who’s going to complain about that?

But the likelihood is that it’s going to take some time. So if you’re prepared for the long haul, you are really prepared, you know what I mean? You are really prepared. If you just prepare, two or three little demonstrations and think “we’re gonna get this,” you’ve prepared on a lot of luck, on a roll of the dice, you know? And you may get lucky. But supposing you don’t, whatcha going to do, drop out? You’ve got to have a long-term view. Social change is a long-term proposition, but that time is not wasted because what you’re trying to achieve is worth the sacrifice of the long-term.

Returning to your work with Freedomways, how do you think, alternative and maybe even student press to a certain extent, can work to advance civil rights and social justice causes? There’s a lot of criticism levelled at us in maybe a similar fashion to people using anti-communism as a cloak for ulterior motives, where people say “you have to be balanced and you have to be strictly objective,” and to a certain extent you do, but they’ll say that when you try to advance a particular cause. How do you think we can advance those causes while either side-stepping that criticism or working with that somehow?

I think you said it very well in the question. [Laughs] Really. You have to have the patience.

Dr. Du Bois said that a long time ago—you must have patience—because great movements take time to build and even more time to win. There are great movements that surfaced and didn’t accomplish their mission, but they left a legacy that we can still look to, of integrity and sacrifice and so forth. And then there are great movements that get over the hump and achieve a certain change and transformation in the society.

Patience is a quality of character that I feel we should work to develop because it makes us more effective and also, it’s a good quality to have in your personality.

How did you get involved in Freedomways?

I knew Esther Jackson from the Southern Negro Youth Congress. I joined the Southern Negro Youth Congress right after the war. In 1946, I was at their convention in Columbia, South Carolina, which was the first time blacks in South Carolina used the city auditorium, and I was asked to read the peace resolution on that occasion.

I continued to ship out as a seaman during the era of the ‘40s to 1950. When Esther asked me if I would like to be an associate member of the editorial board, I was at SCLC, so I told them I was too busy. I had two jobs with SCLC, the voter registration and the fundraising out of New York. So once I had to leave SCLC, the opening was still there. I said, “Well, I’m available now” and she said, “Well, come on.” And that was the beginning of my 20-year association with the magazine.

After a number of years of work with the SCLC, you resigned in 1963 after pressure from prominent liberals like the Kennedys, who were reluctant to work closely with Dr. King if the organization staff had links to the Communist Party. That seems indicative of the era, but what was it like for you when this was happening, when you were getting pressure from all sides?

After a number of years of work with the SCLC, you resigned in 1963 after pressure from prominent liberals like the Kennedys, who were reluctant to work closely with Dr. King if the organization staff had links to the Communist Party. That seems indicative of the era, but what was it like for you when this was happening, when you were getting pressure from all sides?

Well I wasn’t getting pressure from SCLC. When I say pressure, the pressure was coming from the government. We were fighting for a civil rights bill that was going to abolish the last remnants of segregation. I would not have remained in SCLC as a problem.

If they had tried to hold onto me as a member of staff and still put pressure on Kennedy, I would not have stayed, I would have resigned. Absolutely. I was there to help them achieve that goal because it affected my family, too. The pressure was on the organization for me to leave, so we decided I would leave. Okay. [Laughs] It’s no big deal. I went to write for Freedomways and I probably wouldn’t have had time to write for Freedomways if I stayed involved in SCLC.

So it worked out fine in that sense. The SCLC understood very well what this whole anti-communist thing was all about. They were trying to please the southerners in the Democratic Party, who were using the anti-communist issue around anybody who tried to end segregation.

So it became a way for them to attack you, an ad hominem kind of thing.

The anti-communist thing was a convenient cloak for them to put on. The truth of the matter was that they didn’t want desegregation. Ninety-nine congressmen signed the Southern Manifesto [a document drafted in 1956 which held that the desegregation of public schools as unconstitutional]. See, this was their real position. Anti-communism was just another way of pushing that position.

What was it like being a member of the Communist Party during the late ‘40s and the 1950s in the United States? It seems like you joined at a very difficult time to be a member as people were facing blacklisting and expulsion from unions and other organizations because of their political affiliations. What motivated your involvement?

What motivated it was that the Communist Party had played a leading role in building the labour movement. African-Americans recognized that we needed a congress with industrial organization, a new labour movement, because the AF of L [the American Federation of Labour] was not open and a lot of the railroad brotherhoods had white-only clauses in their constitutions.

We saw the Communist Party as an ally in the struggle to end segregation, and that was our primary concern as African-Americans. And they were a strong ally in the labour movement. They really broke down a lot of the prejudices the American labour movement had been historically associated with. They had the right slogan: “An injury to one is an injury to all.” They were very principled in their operations. And if you look at the unions that were considered left-led unions, with communists in them, you can see the distinction in their record as compared with the mainstream AF of L organizations.

So as a young person, and a person who grew up in an industrial city, Detroit, among whose family were not communists, but there were people who were friends of family that were—my aunt was a schoolteacher in Detroit and a number of her friends were communists, black and white—it wasn’t strange to me to be associated with communists in the sense that I knew that the communist scare was a fraud and, as a young person, I just was not willing to accept that.

Communism wasn’t a strange idea. It was strange to a lot of people because they hadn’t thought about communists a lot before, so when the government started this whole anti-communist thing, a lot of people fell into it simply because they had no historical reference to go by that would lead them to think any differently. I understand that, but it doesn’t excuse it because it did a lot of harm to the labour movement. It did a lot of harm to the country and we have been suffering from that ever since.

So, for example, health care reform in the United States recently. As soon as that’s brought to the table, people are pejoratively calling people “socialists” or things like that.

So, for example, health care reform in the United States recently. As soon as that’s brought to the table, people are pejoratively calling people “socialists” or things like that.

And what’s wrong with socialism? [Laughs] I mean, how does it happen that most of the industrialized world has some kind of socialist formation and socialist parties and communist parties? So why is it so dangerous for people in the United States?

There’s no rational answer to that. It’s a game played. And so, when you are out in the world earning a living, you’ve got to understand the game. [Laughs] Don’t let the game get run on you.

Why did you decide to end your membership in the Communist Party and become involved with other parts of the civil rights movement?

I ended my membership because I understood the climate in the country. I wanted to participate in the movement that was going to fundamentally make a change. The communists stood for a change, but they didn’t have the support among the public like in France or Italy or other countries. They did not have the support among the public for the changes that they wished to make, which were very democratic.

I never denied I had been in the Communist Party, I still had communist friends, but I knew the atmosphere in the country would not let you remain in a mainstream organization if they thought you were a communist. They would use that as a bludgeon to scare everybody else [that people] like you had an idea to overthrow the government or something.

So I said well, if I can’t be active in the Communist Party and be active in the civil rights movement, I will choose to be in the civil rights movement because segregation and institutional racism was a concern to me of high priority, as it was to many African-Americans.