Miles Davis’ “So What” plays in the background as the search continues for last remnants of inspiration for piecing together this document. A bit frantic now as the sax solo wails, free to improvise, I’m faced with the reality that my interview subject, the complex and infinite Ginsberg, sees no end.

This exercise involves piecing together a mosaic of reflections, in part representing real life statements and quotes from literary works, including interview responses from his living years. This particular interview is of course contrived; Ginsberg passed away on April 5, 1997. In the spirit of his writing, this study brings improvisation, rhythm changes, and an open approach. Direct quotes are taken from Ginsberg’s poems and essays on the Beat generation. In an effort to understand, one has to dig deep, and it’s best not to stand on the outside. I hope that in my endeavor to take creative license with this document it will be both entertaining, as well as worthy of Ginsberg’s recommendation to “follow your inner moonlight; don’t hide the madness.”

As Miles Davis brings the tempo down, I welcome Ginsberg. He takes a seat. It’s January 19, 2018; I invited Ginsberg to sit with me to explore his evolution as a writer, his relationships with fellow artists, and to have a look at the world as he sees it.

The intention of this interview is to form a better understanding of who Ginsberg was, what influenced his work, and why his work was meaningful alongside the work of others during this poignant time in history. Perhaps in our conversation, a deeper understanding of the Beat generation will emerge, and further revelation on the impact of his work toward creating a culture of change will come.

It’s a personal belief of mine that who we are has been shaped largely by the influences of our past. I’d like to start with you on that note. There has been quite a great deal of documentation regarding the experiences you had as a young child with your mother’s mental health challenges and how these did in fact set in motion much of your drive to explore writing as a way to work through that difficulty.

You were “frequently frightened by fearsome shadows and dark hedges, by ghosts in the alleys and the shrouded stranger that would later appear in poems.” What would you say with regards to this assumption?

Well, I would agree that my mother’s condition was difficult; it did compel me to journal my thoughts. When I was fourteen, I wrote that I was “writing to satisfy my egotism.” One would think I might have become lost in the powerlessness of my mother’s condition. Quite the opposite, I found the power in words, power over how traumatic all of it was. The poetry of my life’s work speaks to that.

This must have drawn you to other artists who were as compelled to write for their own reasons. Who would you name as being the most influential to your work overall?

Whitman and Blake of course were inspiring, and “the interesting thing is I’m an imitator of Kerouac, really, turned on by him, as many are…” His method was raw, it greatly impacted my style. I learned from him that I could write my “thoughts without examining them for literary merit.” The karmic universe thankfully brought us together “in the spring of 1944, while Kerouac was in the middle of a late breakfast of eggs and bacon.” Both of us were at Columbia together. We were introduced to Burroughs during our time there also. Back then, Burroughs seemed the wise elder. He was twenty-nine, so about a decade my senior. When I first met Burroughs, I asked him, “what is art?” He replied, “art is a three letter word” (Watson 35). How’s that for an iconic statement?

So you would say of all the writers you’ve had relationships with, these two are your most profound?

Sure. And as far as writers of the Beat generation, I’d say we “were like a slow burning fuse in a silent vacuum. The postwar era was a time of extraordinary insecurity, of profound powerlessness as far as individual effort was concerned, when personal responsibility was being abdicated in favour of corporate largeness, when the catchwords were coordination and adjustment…” This time was ripe for us, as far as artistry found within the power of our words. I mean, Naked Lunch? Fantastic. “A dystopia where technology strangles all vestiges of freedom…”

Oh, is that your cell phone ringing?

Yes, sorry about that! I’ll turn it off. Thanks. So what you’re saying leads me to conclude that “probably no other literary group has had such enthusiasm for placing intimate matters on the public record as a matter of spiritual and social duty.”

In consideration of this statement, if you could point to one particular piece of your literary work that speaks to this, what would it be?

I would guess that most would expect me to say “Howl,” due to the fact that it came under such scrutiny, and was hit by censorship. You’re aware there was an obscenity trial in 1957?

Yes, your publisher Lawrence Ferlinghetti was arrested. Copies of “Howl” were seized.

Hard to imagine a free country where one cannot publicly make reference to what exists in reality, isn’t it? The take down happened in late May of 1957, at Lawrence’s bookstore, City Lights.

Why do you think your work was targeted?

Somehow, my work was linked to a rise in juvenile delinquency. The attorney prosecuting Ferlinghetti was convinced that delinquent juveniles were stimulated by cultural materials and considered the content in “Howl” representative of those materials. I think the prosecutor’s favourite line was “who let themselves be fucked in the ass by saintly motorcyclists, and screamed with joy.”

You’re smiling. This was surely an amusing side show for you as an artist, but didn’t this change your life significantly after the trial?

Of course. And the irony of the court decision to sanction freedom! How about that? An artist free to be of his own authority, and the public free to choose. Most importantly, perhaps it “shocked the sensibilities,” a recording of “refusing to accept standard American values as permanent.” Bob Dylan, bless him, remarked on my work that it was “for him the first sign of a new consciousness, of an awareness of regenerative possibilities in America.” I am so humbled.

And what would you say to those who continue to criticize your work?

I would dub them “creeps who wouldn’t know poetry if it came up and buggered them in broad daylight.”

Let’s talk about those who do know poetry. Whom would you say surprised you the most as a writer of your generation, and why?

I never said directly how much I admired Diane di Prima for her courage at the time. She didn’t need to push off from the fist of authority as an artist, she simply just engaged in it — lived the art. She set her own rules. Let’s face it, there she was in a male-dominated arena, just being the artist.

Yes, you were an artist during an era “where men were called on to do important things and women were expected to support them in those endeavors. Many of the Beats saw women only as sex objects, providers, and mothers, and rarely did they believe that they could write as well as their male counterparts.” Do you agree?

Absolutely. At the time there was “missed opportunity to discover some remarkable talent…only strong women who were extremely self-confident and self-assured, like Diane di Prima, could break out of the little-woman mold…” In my case, I just simply sought out the company of men more so than women. But she was a respected friend. A strong writer.

You say she lived the art. Her book, “Memoirs of a Beatnik,” is quite something. She writes about an explicit orgy, involving yourself, Kerouac, and others. Then she retells the story as “boredom, cold noses, a cheap phonograph playing a Stan Getz record…” So, what’s the truth?

Exciting hot orgy, or boring cold evening? We are presented with a story and a reality. Which scenario you take as reality will depend on you. That’s your freedom. Question everything. That’s your truth.

Hmmm… okay… I would not doubt the reality that there was a deep and intense relationship amongst the group of you. What are your thoughts on di Prima’s relationship with Amiri Baraka?

That’s an interesting question to ask of me. I’m not sure my opinion on this, or if it is relevant in any way. I’m curious as to why you’re asking.

I would assume your friendship saw intimate conversations. Her relationship seemed a bit precarious? He was married, and she was having his child.

Well, I know she certainly didn’t see herself as the mistress. They created art together, and from this also came a child. We don’t choose whom we get to fall in love with, do we? No. But then Baraka was called to the black arts, and Diane just wasn’t a part of that identity. None of us were. But we understood.

What did you think of his poem, “Somebody Blew Up America?”

When I saw him in 2014, we laughed that it caused so much controversy…“his post as the official state poet laureate of New Jersey was dissolved… he had no regrets about writing the poem. Because the poem was true.” Imagine! Censorship alive and well. So, tell me, how did our howling change anything?

I’d say it stirred conversation, made people question their reality, their freedom, their identity. Question authority. It woke them up.

Yes. Art is a reflection of the struggle. You know, when I returned from India in the 1960s, we were into a “new era of personal freedom, idealism, and experimentation…the interests of this new youth culture happened to coincide with [my] own ideas about the liberation of society… [we were] intent upon questioning authority in all forms, and believed that equal rights should be available finally to all people.” I was fortunate here, this was the progress, my love army for political protest. Yeah it was good, that collective movement. Our Beat wave hitting the shore.

Have you seen the film they made about you?

(Laughs) James Franco, I mean come on! It’s a bit distracting! “With the best will in the world is it ever possible for actors blessed with incomparable beauty to get under the skin of the homely characters they play?” No, I haven’t seen it, I couldn’t bear it.

So you don’t think an actor could represent you or your work in a film?

I am a man “with three thousand years of poetic history behind him… [the] enterprise was not simply to be about Allen Ginsberg, or English and North American literature, but about poetry itself, as history and lineage, as an identifying signature of our human engagement with civilization.”

But you can’t have art without the artist. Bill Morgan compares “the story of the Beats to a freight train, with [you] as the locomotive that pulled the others along like so many boxcars. The Transcendentalist movement wouldn’t have been as tasty without Emerson, but the Beat generation would never have existed without Ginsberg.”

Well, to counter that, “as Ferlinghetti put it succinctly, the Beat generation was just Allen Ginsberg’s friends.” And, of course, you can have art without the artist. Art is life. Life is art. Write about it. You’ll see.

The Miles Davis album playing in the background, Kind of Blue, ends on its last note, and Charlie Parker’s Anthropology begins to be-bop around the dining room table. I feel an overwhelming sense of appreciation for having the luxury of time to meet with Ginsberg and touch on some of his reflections, to imagine conversation, to ask these hypothetical questions. Anthropology seems fitting, as the quick study of this particular culture of artistry and human connection presents so much more to reflect on than can possibly be packed up into one document. Ginsberg is at most an influential and timeless literary figure, and was at the very least an interesting bird.

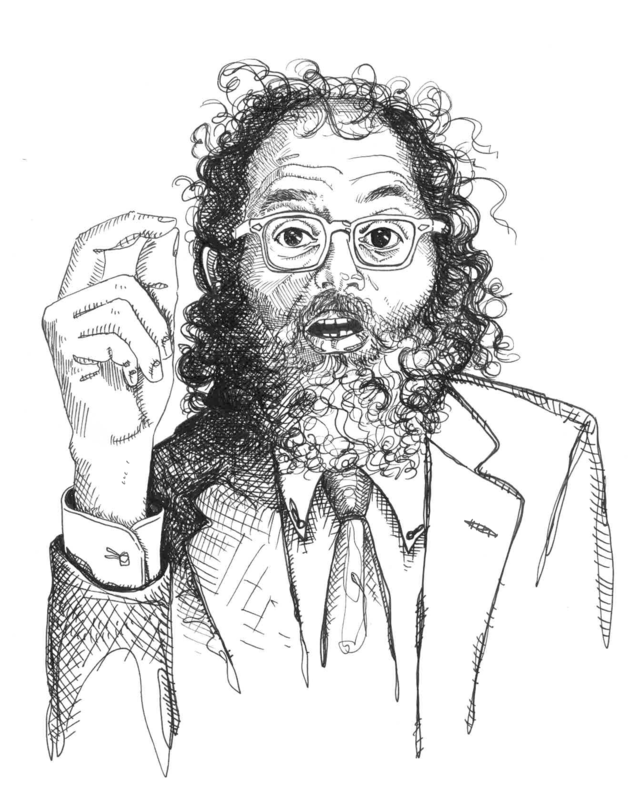

Image: Renée Campbell/The Cascde