By Michael Scoular (The Cascade) – Email

Print Edition: June 5, 2013

There’s a tendency in criticism to elevate slight works by comparing them to their better peers. Mud opens with two invitations: into the dictations of too-familiar coming-of-age and through a lens of classic storytelling. But simply because a work begs to be spoken along with fondly recalled examples does not mean there’s anything to be gained from listing a supposed link.

There’s a tendency in criticism to elevate slight works by comparing them to their better peers. Mud opens with two invitations: into the dictations of too-familiar coming-of-age and through a lens of classic storytelling. But simply because a work begs to be spoken along with fondly recalled examples does not mean there’s anything to be gained from listing a supposed link.

Mud’s opening courts Twain with its two boys (Tye Sheridan and Jacob Lofland) setting out surreptitiously out to open water, and depicts a familiar scene of silent, at odds marriage, but before long it becomes clear Mud is too humourless to be taken as parody, but far too juvenile to be taken seriously.

Its unimaginative derivations and subject matter suggest a Serious Movie, yet the crutch of kid sympathy is most of what the film stands on. Director Jeff Nichols’ midwestern and southern United States settings continue, but here are barely set through lazy shorthand before coming apart at the seams. Ideas aside, there’s enough to find lacking alone in the way realism and allusions to other fictional works unsuccessfully come together.

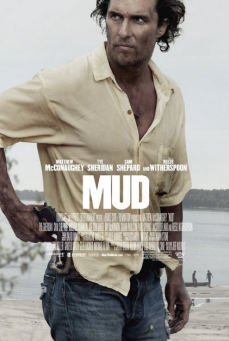

Avoiding dramatic timing but still bestowing Matthew McConaughy with the callsign/nickname/folk myth beginning of the title, Mud is a man hiding out with a past discovered by two “innocent” young boys who come to be led astray or opened up to the real world, depending on your acceptance of the claimed truisms found in the movie’s main character. In either case, Nichols’ tired by full conceit loses any interest from the start through establishing that these are child actors acting fully for the camera, unhelped by the movie’s slack pace. Weak comedy alternates with weak pathos, patches of attempted lyricisim fall in between modern realism, none of it any more than skin deep. At over two hours, Mud, like his forgivably flawed debut Shotgun Stories, dwells on unnecessary dialogue that reaches for sleepy realism, hampered further by how petty the ideas of judgment and how television overdone its crime and relationship status stories come to resemble.

The reason this is a disappointment, one impossible to tell from Mud alone, is Jeff Nichols made an excellent movie two years ago called Take Shelter, a reworking and evocation of mental illness less crushing but arguably better than the similarly themed Melancholia. Its narrative workings both relied upon and provided an extended representation of empathy, in a way that didn’t call for emotion the way any climaxing drama tends to do, instead providing a detailed portrayal of a point of view, one also attuned to financial and familial realities without becoming an Issue Picture. This use of genre is the precedent Mud comes after, and it is baffling to see something so simplistic in thought and ungainly in form result.

Next to the cursing for fun, hormone comparing boys, McConaughy is the weapon-carrying, advice-dispensing, sunburnt and sweaty model they look up to. Applied accent and natural mannerisms strain for credibility, but this is far inferior to McConaughy’s work with Richard Linklater in Bernie and Steven Soderbergh in Magic Mike, two directors who consistently create exceptional performances with their casts in a way Nichols seems unable to do in a major way outside of his regular collaboration with Michael Shannon. With the patience and tension of Take Shelter thrown out for cutting and framing that suggests anonymity, Mud never sets a tone that considers its characters as anything more than pre-determined players.

What makes Mud appalling is its thesis, and Mud is schematic and baldly argumentative enough to use the term. The old guard speaks of how “men need to take advantage where we can” and retaliates with the admonition to “respect a man’s livelihood and property” and there’s some tension between a power imbalanced husband and wife, rebellious son and father, but Nichols resolves it all by affirming core family values and the comfort of happy endings (but so hard earned!). It’s the kind of simplistic but loudly spoken worldview expected from an offering from a hopefully-never-heard-from-again Sundance entry, not a film from a thought-talented director getting a relatively wide release. There isn’t contradiction here – points are underlined and scored to a country conventional soundtrack, and if anyone has seen a dated but still more alive precedent like Stand By Me or Shane, there’s nothing to be surprised by in Mud’s details, save that the person behind Take Shelter could make something so ill-considered and reducible.