By Katie Stobbart (The Cascade – Alum) – Email

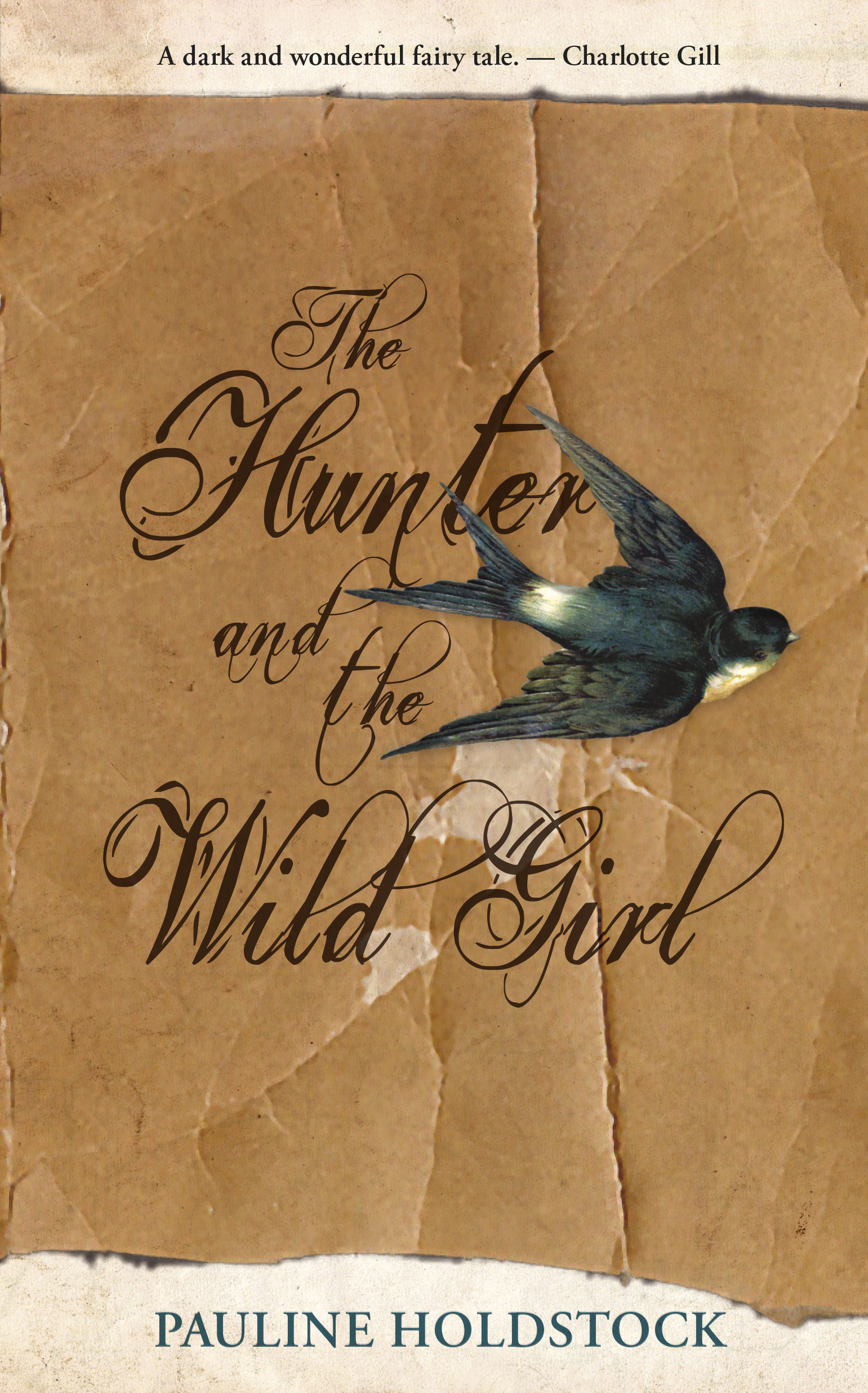

The Hunter and the Wild Girl

By Pauline Holdstock

Goose Lane Editions (Canada)

Released September 1, 2015

It begins with a mad break for freedom, a feral child running from the darkness, chased by men and their dogs through the rural paysage of 19th-century France. It begins, also, with a hunter who can no longer hunt, Peyre Rouff. As the title might suggest, The Hunter and the Wild Girl sets out to navigate the peculiar bond between them, and explores, with poignant, often poetic, and always vividly concise language, what it is to be human.

Though not strictly a fairy tale, HWG courses with mythical lifeblood. A girl appears to have literally flown away; a man haunted by ghosts dwells alone in a chateau, surrounded by taxidermy of his own making; and a band of villagers ventures into the wild scrubland at night to retrieve the wild girl.

It makes sense, then, that author Pauline Holdstock’s “earliest diet in fiction was myth, fable, fairy tale, later the ghost tale,” as she said in an interview with Found Press. “I’m still drawn to those forms for the way they wear such outlandish clothes and yet bring us in the end right up against the most basic and the most universal of our impulses as humans.”

Holdstock also keeps to her reputation for deft, compelling prose and digs elbows-deep into the very real landscapes of love, fear, and grief. From their earliest encounters, the girl is more a source of wakened pain for Peyre (whose name fittingly recalls the French word for father) than light, a reminder that it is not easy to be dragged up from the darknesses we weave around ourselves.

“Now Peyre alone with the vision does cry out, for in the chaos of girl and dog his son has broken through. He rams his fist against his mouth, and his stomach heaves as if he is choking on his own voice… The very thought of her is an iron claw dragging at the coals of his heart, raking them to red life.” Rather than cliffhangers or a series of dramatic peaks, this aching movement out of darkness carries the plot and characters forward. That is not to say there are no moments of action or intrigue, but these are always thick with Holdstock’s true foci: the human and the natural. Reading her work brings an incisive intimacy with her characters, as well as with the natural landscape — its scents and textures are embossed, braille-like, in Holdstock’s prose, and nature is enlivened with its own emotive force. This is true for both the wild girl’s experience of nature as a home or a second skin, and Peyre’s more removed view of it as a representation of his inner landscape, and as a force whose laws of life and death dredge up enduring ghosts and a fierce internal resistance.

“For there were times, times in winter especially, when Peyre looked out on the world and saw there his own soul displayed, laid bare upon the leaden and liverish firmament; when late in the afternoon the grey sky bruised to dark plum, and ill-defined clouds heavy with puce merged with infinity, leaving the mind to guess at their contour. It was his future, this skyscape of dread with its ominous light, that might discover and expose yet deeper chasms within. And when he saw this augury of his life to come, the impulse to pre-empt it rose again and he retreated to his work, or to his mind-erasing lists, finding salvation from his torment.”

Holdstock’s tale is far from ordinary, fathoms-deep, and moving. Although it plunges heavily into gloomy territory, it is worth noting that her troubled characters can often be found looking skyward, drawing not the ominous, but hope, life, and renewal from that “ecstasy of blue.”