By Nick Ubels (The Cascade) – Email

Print Edition: April 10, 2013

I’m convinced T.S. Eliot had college students in mind when he wrote that “April is the cruelest month.”

Yes, it’s that time of year when my fellow sleep-deprived, caffeine-addled undergraduates are riddled with deadlines and projects once neglected and now looming. The longer hours and sunshine beckon us outdoors but we must stay attached to our books and computer screens.

The comfortless truth, my friends, is that we have no one to blame but ourselves, for these assignments have been on our radar since January. But what’s really on my mind is this question: how many of us are truly interested in the research we’re conducting?

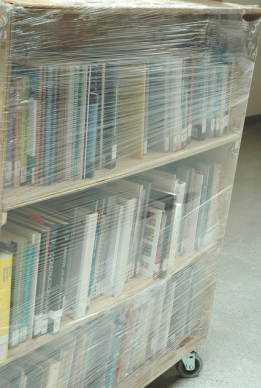

We chose to be here. Shouldn’t the power of original perspectives be compelling us to flood the library during its all-too-brief opening hours?

Judging by the sudden availability of parking spaces at UFV’s Abbotsford campus in recent weeks, I would hazard to guess that this is not the case.

The problem is that undergraduate courses reward stale and unoriginal ideas.

In my years at UFV, I’ve become intimately familiar with the particulars of researching and writing academic papers for humanities courses. From my vantage point, there are two sources that contribute to this disease that is hampering the quality and vigour of our written arguments.

The first is something professors can help to remedy. It can be found on nearly every assignment outline and often looks a little like this: must include at least five secondary sources.

The rigid requirements for citing academic sources shackles students to what has already been said and explored.

Because we are required to cite prior secondary sources in our essays, it is much less work for me to select a topic that countless other academics and undergraduates alike have already beaten to death. In the clock-watching mind of the undergraduate, it becomes so tempting to ditch whatever original or interesting idea we have in exchange for the promise of an ocean of easy-to-find research that supports an unremarkable thesis.

The amount of work that has to go into culling little bits of argument from the range of tangentially-related sources required for an original thesis dwarfs that needed for your run-of-the-mill topic.

I understand the need for evidence. I can appreciate that the requirement for a certain number of secondary sources ensures a certain, minimal standard of research. But the balance is skewed in favour of the short-term gains associated with boring takes on canonical and institutionally-supported topics.

In order to encourage more original thinking, professors must assert their interest in out-of-the-box research questions and find tangible ways to reward students for taking on the extra work required of a truly original topic.

The second problem is something students can help remedy. And that’s fear.

I’ve been there. In my first years of university, I was reluctant to pursue ideas that were daring or new or unconventional because I feared staking my GPA on them.

The truth is that an undergraduate degree is the time to experiment with ideas and types of arguments. (Unless you’re in Tim Heron’s Milton class. Seriously. That man has his own 100-page style guide.)

To be clear, I’m not suggesting handing in a series of haiku for your next upper-level Tudor history paper (This seems like a good place to note that The Cascade assumes no responsibility for the grade any paper inspired by this editorial might receive). There are certain stylistic and academic conventions that do need to be followed to allow for equitable debate.

What’s the worst could happen? You bomb your midterm paper? Then play it safe for your end of term essay and study like hell for your final. One hundred and twenty credits means plenty of opportunities to boost your GPA.

I’ve found the opposite to be true. Professors can see the extra work that goes into an original idea. If you write something that actually sparks their interest, their gratitude for relieving them from the monotony of 30 papers that draw on the same five boring subjects.

Take chances, make mistakes, and draw from different disciplines. Cross-disciplinary pollination yields delicious academic fruit.

By stifling creativity at the undergraduate level, we’re only reinforcing tired ideas at the higher levels of university thought, or worse, disenchanting and alienating our most original thinkers before they get the chance to take full advantage of our institutions of knowledge.

We’re institutionalizing conformity to old ideas and opinions. It’s a problem that will only feed itself until we decide to address it head on.

So as all of us write our last papers of the school year, and some of us put the final touches on our UFV credentials, I urge you to take the academic road less travelled.

You might be surprised what you find.