Prior to the show, I was directed to a dingy alleyway. It was apparently the “quietest” place to record the interview. I took in the sights as I waited: a shattered full-length mirror, a broken DVD of the Pixar movie Up, a random spare tire, upon which I rested my laptop. Vancouver certainly has its charms.

“I wanted to do this for a while,” said James Thornley-Hall, who previously “jumped in and out of a few bands,” but never connected with any of them. Thornley-Hall, who plays bass, put out a call for anyone interested in starting up what he called “a power violence project,” which is how he connected with Charlie Kratz. “I wanted an outlet for the kind of music I like,” said Kratz, the band’s guitarist and unofficial “band dad.” “That’s part of why I wanted to get rolling with James Thornley-Hall.”

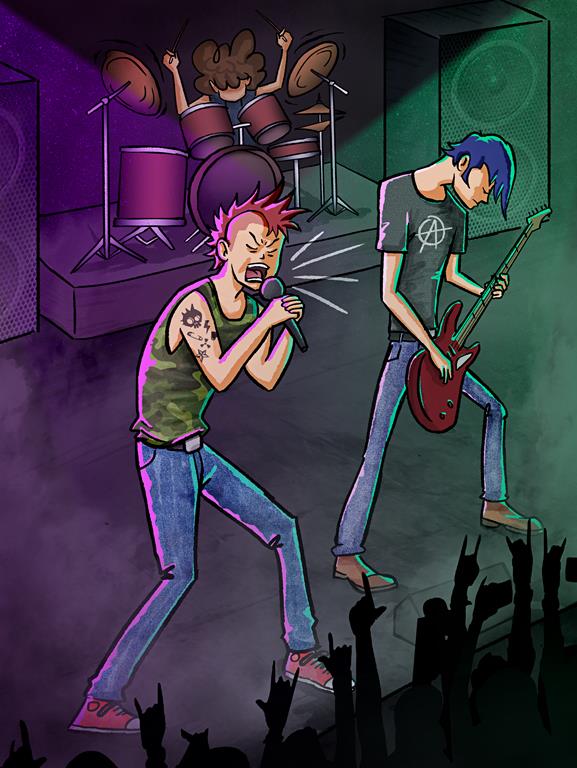

I had met lead vocalist, Jacob Ainscough, by chance when I spotted his mullet in a crowd of film students at a party. “I started going to outdoor shows at Victory Square,” said Ainscough, but that he “wanted places to mosh.” In the crowd, he overheard someone mention the Bullet Farm, which led him to meet Thornley-Hall. Ainscough also introduced Salvodor Chavez to the group as the glue that holds the band together, “Chavez is the drummer. Keeps our time. Leads a lot of the jams.”

Ainscough described his intro to punk/hardcore in a way that was extremely sentimental for a man I’d just seen screaming about the housing crisis: “I remember right when the first song was played,” he said, “and I was sucked into the vortex of the mosh pit. I knew that I wanted to be a part of this community for the rest of my life.”

As Kratz inspected a flat tire on the band’s black station wagon (very punk rock in my opinion), I asked Ainscough what he draws on for lyrical inspiration. “Sometimes it’s about war. Sometimes it’s about causes I care about. We’re a hardcore band and those tend to be topics that resonate.” A hallmark of punk is its lack of structure and norms. Ainscough looks for inspiration in history and the dark corners of his mind, but sometimes some of his songs are about nothing in particular. “Drinks, beverages,” says Kratz from the background as he fiddles with a spare tire. “Interview first, tire second,” replies Ainscough… “What I sing about changes depending on how I’m feeling, what’s on my mind, what’s in my focus, especially during the jams.” The “jams” as Ainscough calls them, are what sets Desperate End apart from other punk bands in the industry “We don’t have to be a certain way. We can just be us… I don’t have to put a label on it — it’s how we’re feeling.” Kratz elaborated, “People like a sense of authenticity.”

I was curious about how the band got its name. Kratz explained he was, “falling asleep one night and thinking back on past relationships … how you think about the end of relationships or the end of a person’s life; sometimes that’s the way it goes out, it’s a desperate end.” Definitely a band name with more thought put into it than my highschool business teacher’s punk band, the “Surreal Bananas.” Desperate End has a very intimate relationship with mortality. Ainscough mused, “you know, doing what I do, it’s what death feels like, what grief feels like.” To which Kratz agreed, “anything feels like everything ends.”

I wanted to know what advice they could give to punk bands coming up in the Vancouver industry. “Every opportunity is not a good opportunity, play shows with purpose” said Kratz. Thornley-Hall tacked on, “Do it because you love it. The money’s not gonna come rolling in, at least not right away.” Standard advice you would give a struggling artist. However, what really stuck out to me was Ainscough’s philosophy. “Memento mori,” he said — part of why he even got into this in the first place. “One day you’re going to die, so instead of waiting to do things — waiting for tomorrow to say yes to joining a band — just say yes to things now.” Chavez explained, “Shit takes time. Everything in life takes a while to figure out. People run into bombs along the way. Be patient. Be stubborn. Practice and do what you love. Music is a beautiful thing. It’s worth the wait and the patience. Learn some shit, learn some rudiments. Theory is good.” Listening to all of this, I felt tears forming — until Kratz uttered his final advice: “Always carry a spare tire.” I just might!

Leaving the interview, I felt a sense of sadness — possibly because I had been letting life pass me by. These four guys seemed scary on the outside. How could you spend four hours screaming into the ether and then go home and pet a puppy? I didn’t know, but after spending some time with them, I got to know them surprisingly well. The atmosphere was electric, but from the pool noodles in the mosh pit, to the boys explaining how much they despise the rats at the venues they play, I felt safe. Punk is a hidden joy that is rarely explored. While it may seem intimidating, it’s simply another way to heal from trauma. In the same way Taylor Swift is for the girlies going through it, punk is for the misunderstood that need an outlet.

Gianna Dinwoodie is currently working towards her BA in Political Science and hopes to pursue a minor in Journalism. When she is not seen writing mountains of essays for her classes, she enjoys poetry and literature of any sort. Especially of the horror or psychological thriller genre! Don't ask her to watch a horror movie though, she'll probably cry...