The soulful and bluesy sounds of the Mission-based band, Swamp City, filled the Skwah First Nations community hall Friday night. There was dancing and laughter, and tables filled with people munching on snacks while enjoying water from small, flowery teacups. Despite the casual atmosphere, the community’s presence was for a more serious reason. The Wet’suwet’en Strong benefit concert was hosted by the Skwah First Nations in an effort to raise awareness of and support the land defenders at the Unistot’en camp, who are trying to stop the Coastal Gaslink (CGL) pipeline that is planned to run through the Wet’suwet’en Nation’s territory near Houston, B.C.

The evening began with a traditional opening ceremony led by Eddie Gardner, a Stó:l? elder from the Skwah First Nation in Chilliwack, B.C. and an elder-in-residence at UFV’s Chilliwack campus, and Ronnie Dean Harris, an artist, hip-hop and poetry performer, and facilitator based in Stó:l? Territory. In a Facebook post about the event, Gardner said that this evening was about raising awareness of Wet’suwet’en, Gitumt’en, and Unist’ot’en people on the front lines who are standing up against destruction of their land, water, and traditional food sources.

“This is their last stand, as most of their land has already been usurped, taken over and occupied by others,” Gardner said in the post.

The TransCanada pipeline is planned to run from the outskirts of Edmonton through B.C., all the way to the energy company LNG Canada’s Kitimat port facility on the west coast where the liquified natural gas will be exported. The pipeline is to be built by the company’s subsidiary, Coastal Gaslink. Late last year, hereditary leaders from all five clans of the Wet’suwet’en Nation called for a stop to the construction due to the fact that free, informed, and prior consent for the project was not obtained from them.

“The five clans of the Wet’suwet’en will never support the Coastal Gaslink (CGL) project and remain opposed to any pipelines on our traditional lands. There is no legitimate agreement with CGL as reported in the media,” Chief Kloum Kuhn, of the Laksamshu clan, said in a press release from the Office of the Wet’suwet’en.

The Unist’ot’en house group camp on Wet’suwet’en territory was set up in 2009, in response to the proposed construction of the pipeline. Since then, a global outpouring of support has been seen for the land defenders, and many people are travelling there to support and to learn while also providing their skills to the camp. Many other clans on Wet’suwet’en land have also set up their own checkpoints in support.

“Folks in the community realized that they needed to reoccupy that territory, thereby proving that this isn’t just backcountry, this is unceded territory that is being used by the communities,” said Mike Goold of the Stó:l? Research Centre. Goold is Wet’suwet’en, and works on rights, titles, and referrals cases at the People of the River Referrals Office in Chilliwack. When the Kinder Morgan pipeline was first proposed (another pipeline project that runs through B.C.), his office was tasked with reviewing the existing pipeline, advising leadership, and helping them decide how they would like to move forward.

Governance over the Wet’suwet’en Nation is hereditary, and made up of a matrilineal system of 13 houses, five clans (Gilseyhu, Laksilyu, Gitdumt’en, Laksamshu, Tsayu), and 38 house territories, including the Unistot’en house group. Five hereditary chiefs represent the five clans of the Wet’suwet’en nation and maintain the final jurisdiction over decisions to do with the land.

In an effort of reconciliation, Canada has committed to implementing the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People (UNDRIP). The UNDRIP is an international constitution intended to enshrine the rights of Indigenous people in all countries. It is the product of 25 years of deliberations among U.N. member states and Indigenous groups. So far, numerous acts in this constitution have been broken.

In January, videos surfaced online of armed RCMP destroying and climbing over the barrier at the Gitdumt’en territory checkpoint in order to grant access to CGL employees. This was in response to a court-ordered temporary injunction issued to the company that prohibited the Wet’suwet’en from interfering with CGL work and would grant them access to the territory to do survey work. The RCMP forcibly removed and arrested 14 land defenders. This violates Article 10 of the UNDRIP, which states Indigenous people should not be forcibly removed from their land. Article 26 is being violated, in which Indigenous people have rights to the land, territories, and resources that they have traditionally owned; as is Article 32, the right to the requirement of government to obtain free, informed, and prior consent before beginning any projects that may infringe on Indigenous rights; and Article 18, the right for Indigenous people to participate in decision-making matters that may violate their rights. On top of that, the temporary injunction order that was issued to CGL only permitted them to do survey work, but they have been widely documented bulldozing and destroying the land. Upon looking at the Environmental Assessment Certificate issued to CGL, the instructions state that all tenure land holders will be notified six months in advance of this construction, which the Unistot’en camp claims they did not do.

Coastal Gaslink has also been breaking Canadian laws. In January, multiple news sources and the Office of the Wet’suwet’en reported that Wet’suwet’en traps had been cut and piled next to a cabin, and land had been bulldozed by Coastal Gaslink. This meant that CGL violated the B.C. Wildlife Act. Section 46 states that “A person who knowingly damages or interferes with a lawfully set trap commits an offence.”

The Office of the Wet’suwet’en released a statement on Jan. 25, which stated that CGL was in violation of its work permit because the appropriate archaeological impacts assessments had not been completed. Coastal Gaslink has stated that they had completed the assessments, but the statement from the Wet’suwet’en said that there was no way to properly do these surveys until the spring of 2019, when the snow and frost had cleared.

Then, on Feb. 15, construction on the pipeline was ordered to stop after two stone tools were found on the property where CGL planned to build its workers’ camp. Archaeologists say the tools could date back 2,400 to 3,500 years.

It appears that many popular Canadian news sources don’t promote First Nations news or cover it as in-depth or as continuously as they could. Indigenous media and news remains separate from these news sources. Global News, CTV, The Province, and the Vancouver Sun don’t feature any Indigenous news on their main pages nor do they have links to Indigenous sections. The Province and the Vancouver Sun both have entire sections on the front page for sports; CTV, Global News, and The Province have links to cannabis sections, but nothing about First Nations or even a visible link to First Nations news. “Indigenous” or “First Nations” must be typed into the search bar for news articles on Indigenous topics to even show up. CBC is the only site of these five major news sources that has a link to an Indigenous section. While the media is still accessible, it is not promoted and therefore has the effect of keeping it out of reader’s minds. It may not be on the radar of most student’s attention, but if more interest is generated among our community, the media will be forced to take a look at it on a deeper level. There is evidence of broken laws and violated rights to be concerned with here, and we need to start asking about it because it affects us all.

“So there’s so many aspects that I would hope the non-indigenous community would familiarize themselves with and learn from and there’s a lot of aspects of my community that we don’t see covered in the headlines and the major stories that are happening there,” said Goold.

The complication of consent stems from how permission to build through First Nations territory was obtained by CGL. While CGL state they obtained consent from all First Nations communities, they have only obtained consent from the elected leaders. In order to truly obtain free and informed consent, they must consult with and obtain consent from the five hereditary leaders, as elected leaders have no say over what happens with the land. Coastal Gaslink hasn’t obtained their consent, so they have no right to say that First Nations along the pipeline route have consented to the project, which is exactly how they’re trying to frame it.

Looking at the two systems of governance more carefully will show us that the body of elected leaders was imposed on First Nations through the Indian Act, which was put in place in 1867 by the Canadian government.

John A. MacDonald has been recorded as saying in 1887: “The great aim of our legislation [the Indian Act] has been to do away with the tribal system and assimilate the Indian people in all respects with the other inhabitants of the Dominion as speedily as they are fit to change.”

Justin Trudeau has said in a recent town hall meeting in Kamloops, B.C., that the Indian Act is a “colonial relic.”

While some elected leaders have publicly consented to the project and signed agreements with CGL, hereditary leaders have not. The media and government tend to portray this as a complicated issue, but it really isn’t; hereditary leaders must give their consent. The cooperation of the elected leaders with CGL also isn’t complicated when you look at the difficult conditions some of the Northern Indigenous communities are faced with.

“They are living in third-world conditions and I do not harbour any resentment towards the elected chief and council … especially the ones that are very remote and well off the highways, not close to any municipality … looking at the amount of money that’s available if they agree to the pipeline, they never had a deal on the table like that, they’ve never been to the table before and it’s an impossible situation for them to be expected to turn down an opportunity for them to lift their people out of poverty. But that poverty has been imposed on them by so many other resource extractive sectors both in and out of the territory and all the successive governments that have marginalized us for the last several hundred years. At least a fraction of my community up North have enough strength left to say no,” said Goold.

Most First Nations in B.C. have never signed treaties ceding their land, including the Wet’suwet’en nation, yet the Government of Canada still holds the title. We at UFV reside on unceded Stó:l? territory, land that was “acquired” by the Canadian government and has never been returned.

Indigenous communities have a long history of attempts to seek recognition of ownership and Aboriginal title over traditional land and resources. The Gitxsan House of the Wet’suwet’en Nation recorded one of their first acts of publicly asserting ownership as occurring in 1872, when chiefs from the house blockaded the Skeena River from trading and supply boats in an effort to protest the actions of miners on their territories.

Further, see the case of Delgamuukw vs. British Columbia, when thirty-five Gitxsan and 13 Wet’suwet’en hereditary leaders took the Canadian government to court to stop logging on Gitxsan territory. The case began as early as 1984 and wasn’t resolved until 1997, after over a decade of fighting through all levels of the court system. The case concluded that the Government of Canada had no right to extinguish Indigenous peoples’ claim to the land. According to the Canadian Encyclopedia the case “defined Aboriginal title as Indigenous peoples’ exclusive right to the land, and affirmed that Aboriginal title is recognized as an ‘existing Aboriginal right’ in section 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982.” So, we see that even though the courts have recognized the title to the traditional territory of the Wet’suwet’en Nation to be one of their exclusive rights, the land has never officially been returned.

Goold, who grew up calling himself Gitxsan Wet’suwet’en said: “[The Delgamuukw court case] really took its toll on the relationship between the Gitxsan and the Wet’suwet’en and there was not consensus in leadership on how to proceed at a number of different points. So much so that even though we won the court case that laid the groundwork for a title case we no longer had the consensus and the strength within to continue with yet another court case to prove title.”

Because of the lack of consensus and deterioration within the relationships of the two tribes, a rift opened between them.

“After the mid-‘90s, I was told that I was no longer Gtixsan Wet’suwet’en, I am just Wet’suwet’en… There was a political break between the two and it went right through the middle of families that had members on both sides. We have been healing from that political break ever since, and we’ve come a long way. We are once again a strong and united tribal unit, but we still to this day have the Office of the Wet’suwet’en and the Gitxsan have their own office.

“It’s an example of the toll [it takes] when First Nations are faced with legal challenges over decades. … It divides us and it weakens us,” said Goold.

A statement released on Feb. 7 by the B.C. government states that the Province of British Columbia has agreed to start a new path of reconciliation with the Office of the Wet’suwet’en, but the Unist’ot’en clan has responded on their Facebook page saying that they are not involved in this conversation. The statement refers to this as an “optic of reconciliation” and the Unistot’en continue to demand that all work on the pipeline stop before they will become involved, stating, “We do not believe reconciliation is possible when our Wet’suwet’en people face the barrel of a gun … the Office of Wet’suwet’en negotiations do not represent Unist’ot’en interests.”

The strain of an ongoing battle to have not just one’s rights, but also one’s way of life and culture acknowledged, can manifest itself as more conflict and trauma. This has been the case for some Indigenous communities as legalities have systematically broken clans apart and keep furthering that divide. According to Sakej Ward, an Indigenous governance department member from the University of Victoria who spoke at the Wet’suwet’en Strong benefit concert on Friday, this constitutes cultural genocide: a term used to describe the deliberate destruction of the cultural heritage of a people or nation for political, military, religious, ideological, or racial reasons.

The Government of Canada, despite knowing that the Indian Act is problematic, are still using it to get their own way. The hereditary system of governance is not new and politicians should have been acknowledging it years ago, as the Trudeau administration should also have carefully and thoughtfully done before it got to this point. It is not appropriate to tip toe around it and play dumb after.

Peter Grant, the lawyer who worked on the Delgamuukw case said in a recent interview that, “For over 21 years, the governments of Canada and B.C. and any lawyer who has done any level of Aboriginal law would understand that when you’re dealing with the Wet’suwet’en people … on traditional territory, you’re talking about a system of hereditary chiefs.”

The divisions the pipeline has created doesn’t stop with First Nations communities. It seems everybody has an opinion on the matter and it is dividing all of us. But this is by design. We are pointing fingers and placing blame on each other, but the people who should be called out are the major oil and gas companies and the banks that support them. And this may be hard to hear, but we are all paying for the pipeline and supporting the violation of human rights in ways that we don’t even see. It is very likely that the bank you keep your money in has a hand in this project. Royal Bank, TD, CIBC, BMO, and numerous other banks are lending massive amounts of money to Transcanada for the pipeline.

“It’s oil and gas companies that are signed with those pipeline companies … [that] stay out of the limelight; they don’t have to deal with the backlash, they’re not the ones that have to deal with First Nations. I feel pipelines are more of a distraction distracting us from who the real players are, and I don’t think the average citizen understands that,” said Goold.

Furthermore, both the federal and provincial governments are subsidizing oil and gas projects with our tax dollars. Just take a look at your paycheck, your investment portfolio, your CPP, or your pension fund and you will most likely see oil-soaked money.

“I found out the hard way that … all of my money was sitting with major banks and oil and energy companies and all the rest … it goes to the bank. If it’s one of the top five or six major banks, most likely they are bankrolling oil and gas companies.”

If you’ve ever considered switching to a credit union, the time is now.

“When I sit back and look at my paycheque I realize the pipeline companies are laughing at me because they’re building a pipeline with my money … they’re not building it with their own money, it’s all heavily financed through banks and other people’s pension plans; they don’t want to take any risk with their own cash,” said Goold.

As students with the privilege to attend university, we have the resources to learn about these historical issues on a deeper level. The truth is, we have all been lied to. Settlers and Indigenous people alike have been fed misinformation growing up, and the history books haven’t fully or completely recorded the atrocities that have been imposed on First Nations since Canada was established. It is our national shame, but we have an opportunity to educate ourselves and do something about it.

“Everything that leads us to our opinion of First Nations and their place in this country has been built up over our lifetimes, and for many of us, it could take the rest of our lives to deconstruct and rebuild that opinion,” said Goold.

We have seen, on a global scale, that the pursuit of a wealthy state and a booming oil industry have so far resulted in social and environmental devastation, especially in Indigenous territories. We can’t keep going down the same path knowing that it leads to nothing but a violation of human rights and the destruction of the environment, because there is no light at the end. We can’t expect a sustainable energy industry to magically pop out of the ground, because it never will. We need to be actively demanding a shift to sustainable energy sources on a large scale and with vigor. If we allow one-sided economic argument to dictate how we run our society, we leave no room for innovation or growth in new industry. First Nations communities deserve more than one option for development. More importantly, governments need to listen to their people. We can’t allow the violation of humans rights in the name of jobs and economic growth.

Indigenous communities and land defenders have made it clear that this is about more than just economic growth and resources. “These are not resources, this a life force that we have relationships to,” said Mel Bazil, a Wet’suwet’en activist, teacher, and UFV alma mater, in a recent video. Mel helped to establish the Unist’ot’en camp in 2009.

By violating traditional land and ignoring Indigenous voices, the Canadian government is further damaging the relationship between themselves and the First Nations people. The Canadian government has put $40 billion into this pipeline (the largest private sector investment in Canadian history), money that could have gone far in Indigenous communities. The Trudeau administration and all politicians need to stop spouting off reconciliation rhetoric that they have no intention of following through on. Trudeau has said that “It is not for the federal government to decide who speaks for [the Indigenous community],” but he has proven himself to be a hypocrite by doing so anyways.

This rhetoric is wearing thin. As stated by Goold

: “In First Nations communities, we’ve been hearing that term [reconciliation], for a long time. It feels like a government term; it’s a made up word that doesn’t carry much meaning anymore because … government officials are getting very good at government speak. They sound like they understand what they need to do … but there’s been nothing changing that indicates that there is ever going to be a balance in power or a change in the jurisdiction.”

We all get it: we need money, we need jobs, we need economic growth, but this shouldn’t be reduced to just an economic issue — this is a major human rights and environmental issue. We also can’t let it divide us, because without the protection of our environment, future access to all of our rights as people will be impossible as our resources will be polluted, scarce, and corporatized.

“[It’s] everyone’s responsibility to uphold environmental justice, for the benefit of future generations and in honour of our ancestors,” said Gardner.

This issue impacts everyone. If not now then 10 years down the road, or less, as climate change is rapidly altering our environment in many ways. We can take action by just being aware of what companies we support, switching to a credit union, demanding green energy sources, and being vocal to companies about what kind of behaviours we want and expect to see from them. Give your local MP a call or an email and look up the supporter toolkit available from the Unistot’en camp website. Seek out Indigenous media sources like the Aboriginal Peoples Television Network (APTN) and search for and read Indigenous and climate articles on popular news sources; they keep track of what you look at and if they see more people viewing a certain type of article they will be encouraged to cover more about that topic. More importantly, educate your peers about what is going on. We are the ones with the power to change. We are the ones with the voice and the voting power to demand our government follow through on their promises and begin to shift our economy in the right direction: away from bloated corporations with a monopoly on resources that don’t belong to them, and towards the rightful owners of the land and citizens of the country, so that we can all benefit, together.

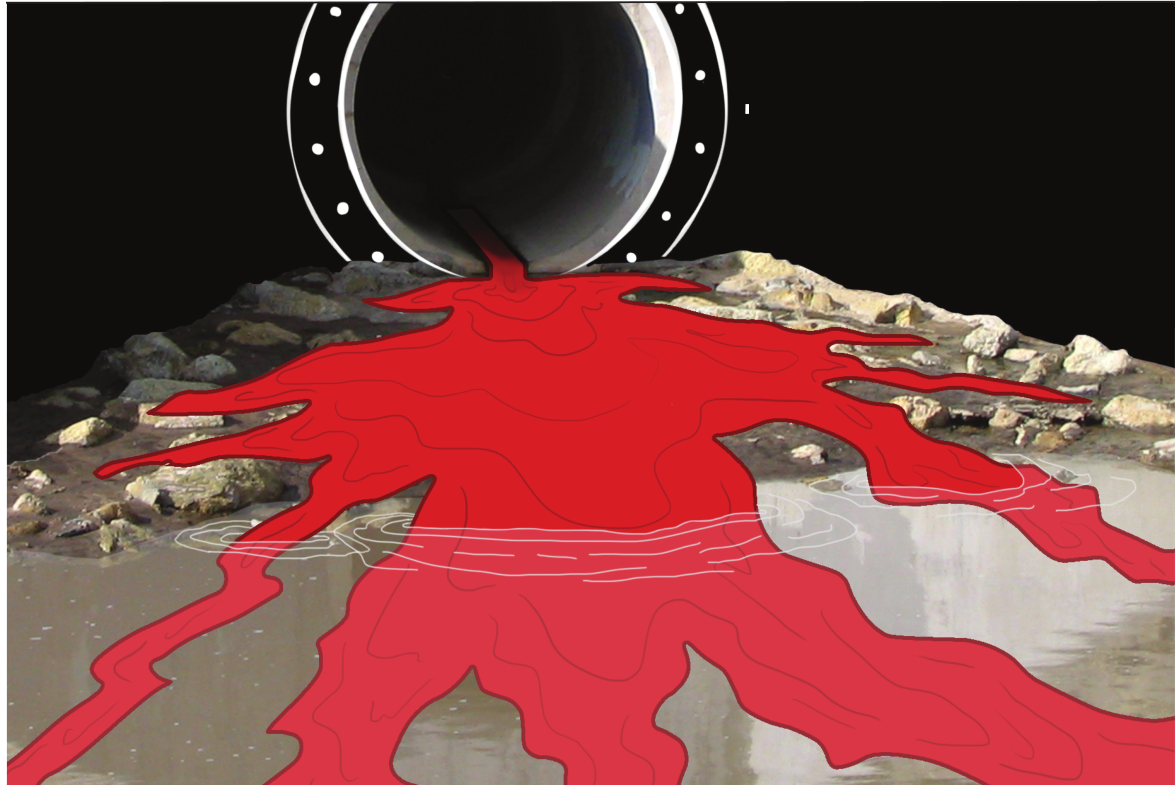

Image: Mikaela Collins/The Cascade

Darien Johnsen is a UFV alumni who obtained her Bachelor of Arts degree with double extended minors in Global Development Studies and Sociology in 2020. She started writing for The Cascade in 2018, taking on the role of features editor shortly after. She’s passionate about justice, sustainable development, and education.