By Michael Scoular (The Cascade) – Email

Print Edition: June 20, 2012

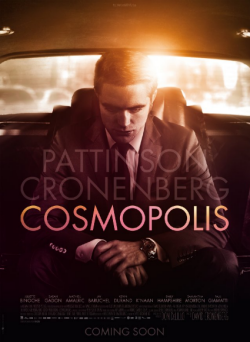

Don DeLillo’s words form sentences comprised of ideas, whole, teeming and stacked, teetering as pages and minutes pass, images for the back of brains that require not a similar volume of vocabulary, but a spot on the same wavelength to strike with immediacy at the senses. By adapting DeLillo’s Cosmopolis for the screen—the dialogue word-for-word in most places—David Cronenberg complicates an already complicated assembly of ideas and subjects, adding to the stir the voices of actors and his own current sense of visual timing.

Don DeLillo’s words form sentences comprised of ideas, whole, teeming and stacked, teetering as pages and minutes pass, images for the back of brains that require not a similar volume of vocabulary, but a spot on the same wavelength to strike with immediacy at the senses. By adapting DeLillo’s Cosmopolis for the screen—the dialogue word-for-word in most places—David Cronenberg complicates an already complicated assembly of ideas and subjects, adding to the stir the voices of actors and his own current sense of visual timing.

Robert Pattinson is a manipulator of subjects, living numbers and advisors that pass through the screen of his limousine, a proprietor of statistical and material largeness, and, reports say, in danger. The focus of Cosmopolis, though, is not the plot, but the analysis of all its moving parts. Analysis might be the best way to describe what Pattinson’s character does; when he’s not locked on the blue glow of his financial displays, he’s looking straight ahead as if he’s still watching people behind the block of his sunglasses, even though he left them somewhere he can’t remember.

This mode, fractured between the desires of the flesh and the tendencies of technology, is assumed by all the main faces of Cosmopolis. Words and body language don’t vary wildly in inflection or display but spill out categorically, syllable after syllable, stance after stance, betraying nothing, seeking to penetrate.

Their syntax is based around the query/responses of commands, like the computer system in The Fly. Their sound oscillates between the day/night dichotomy of speaking and not speaking. This is what. It’s either talk racing ahead, heads lagging behind trying to deconstruct what was just said, now said a minute ago or smothered silence. This is true. What happens to humans in the technological age and the effects of the talking cure are among the most prominent sources of wounds and cures David Cronenberg keeps coming back to, and Cosmopolis holds true to this seeking.

The digital has also changed Cronenberg in ways that have a stark discharge – in the look and pace of his images. There are much fewer sustained shots; instead, Cronenberg prefers an assortment of angles that he shuffles through, trying to find the one that will reveal the most about the current speaking subject. This quicker relay of shot-shot-reverse shot is of a streak with A Dangerous Method. The discussion might not match the intensity, visually and otherwise, of the first meeting of Jung and Speilrein, but they have a similar tenor, of looking for what isn’t revealed, travelling as near as individually possible to the edge of thought. Stare at something long enough and it’ll become unfamiliar.

What is familiar is the topic of discussion. All of the scenes in Cosmopolis are soaked in the context of a financial crisis—the book’s, not the world’s—but close enough that the meaning of what’s said and what’s implied might come across as a comment on every bit of news that’s come across your desk or screen in the past four years or so. Roles are delineated so clearly they might come to resemble the metaphoric. Cosmopolis, with its topical addresses and stripped appearance, could be taken as a harangue. This takes the plagiarized scroll of the ticker at face value.

If Cosmopolis deals in metaphor, it does so with as much force as all of Cronenberg’s other films. They are didactic in that they suggest the only adequate response is rejection. Of what is to be decided. There are characters and there is the world, and Cronenberg has always changed what is accepted as justifiable for both into, well, something else. There are many situations, from the joyous to the unreal, that are even funny here, but there is the blanket of unrest that means that isn’t how everyone will react to them.

And lest the thought that Pattinson is nothing but a blankness take hold, consider what he’s looking for. More, in the tradition of the would-be immortal Videodrome contestant. Bodily and sexual limits, the expectations of being a son, the archaic attitude of everything that’s been surpassed weigh on him. Let it express itself. He wants a haircut at the place he’s always gotten one. What’s unimportant about that.