Print Edition: July 18, 2012

Objects of affection and desire encircle the worlds of Magic Mike and The Amazing Spider-man, movies that are related in the idea of selling an image—a body, a performance—while tied to, yet briefly separate from, a domestic and social reality, but diverge in how they navigate this terrain.

Objects of affection and desire encircle the worlds of Magic Mike and The Amazing Spider-man, movies that are related in the idea of selling an image—a body, a performance—while tied to, yet briefly separate from, a domestic and social reality, but diverge in how they navigate this terrain.

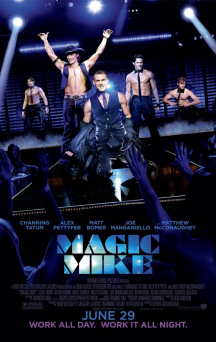

Steven Soderbergh especially, though not exclusively of late in his career, has committed hard-spun genre deviations to the screen, infusing the expected with plausibility—digital infusions of realness—often blurring the line between actorly charisma and natural presence. The group of (theoretically) hands-off, eyes-on physical entertainers of Magic Mike (Channing Tatum, et al.) embodies the comradely bonds of the sports drama, but with the ever-present reminder of earnings to persistently account for.

Day and artificial light is an unbeautiful thing to wake up to, conduct business under, and walk in, wrestling with the futility and unconsidered meanings of language. The only time the cover of yellow relents is when night falls and the dancers and eager audience come out; the liberating stage takes hold of the camera. It’s the play between the two that underpins every scene in Magic Mike, unbalancing a scene of dialogue or sexual appetites.

If there’s any guiding principle to the success of the superhero genre, it is the pursuit of believability, even in an inherently unbelievable concept. Every ability, villain and tendency must be explained – grounded in reality and argued for with charts and graphs. So it follows that in The Amazing Spider-man Peter Parker (Andrew Garfield) gets an added backstory that (sort of) explains everything about his newfound abilities.

If there’s any guiding principle to the success of the superhero genre, it is the pursuit of believability, even in an inherently unbelievable concept. Every ability, villain and tendency must be explained – grounded in reality and argued for with charts and graphs. So it follows that in The Amazing Spider-man Peter Parker (Andrew Garfield) gets an added backstory that (sort of) explains everything about his newfound abilities.

But more emphatically, as a prelude to the full-blown boy/girl, hero/monster fantasy, every available culled-from-reality moment is injected into Parker’s summary adolescence. There’s the love-radius stammers, the way a son helps his father with house chores, the structure of a shouting match, the method of treating bruises. All converge to make this unreality a lived-in one, though one slightly undone by the dissolution of obligations, voicemails from the President and, most critically, The Great Power.

At one of The Amazing Spider-man’s lowest points, a teacher addresses a class (which might as well not exist; we’re only focused on Peter), theorizing that there is, in fact, only one basic fiction story: “Who am I?” The pointed reference to Peter’s supposed struggle is not only not the best summation of the commercial cinema emblemized in Spider-man’s adventures (that would be Willem Defoe’s Green Goblin: “we’ll fight again and again and again and again until we’re both dead”), but sidesteps acknowledging the type of narrative variation going on in something like Magic Mike.

There is no question Channing Tatum’s character and his questioning of where he wants to end up in life is a big piece of the momentum of the movie, yet the very act of depicting the Tampa clubs and the people that frequent them, and particularly in the navigation of Mike’s relationship with Brooke—the sister of his protégé, played by Cody Horn—is more of a “Who are other people,” and not in a self-serving way. It is by acknowledging the failure to communicate perfectly from a personal, limited viewpoint that Magic Mike opens up its characters as more than people to ogle at or sleep with, without being harshly critical.

The issue of identification is never brought up except as an opportunity to be snarked down in The Amazing Spider-man, probably because the image of the slightly outsiderish confused-male-as-hero is the sort of projection-ready comic fiction that wants to be sealed off from criticism. There’s nothing challenging (for Peter or us) about the thrown together love with Gwen Stacy, who is told to “shut up” and needs to be alternately thrown aside and leaned on, as vivid a portrayal of immature myopia you’ll see – only here glorified.

The sexual lines in Magic Mike aren’t crossing any barriers, taking heteronormative relations to their breaking point (Matthew McConaughy’s “You are…” speech spells it out) but seemingly no further. But where Spider-man’s readymade “just like you” heroism and adolescent evocation cynically expects nothing more than willing hearts on the part of its audience, Magic Mike’s dance scenes and interrogative dialogues twist between having males as its main characters and being seen through a female gaze.

It is also noticeable how ownership of narrative grows throughout the film. While both the title character and Alex Petyfer’s rising star drive the story forward, they are never far from other people who have as much of an impact and importance in their events and ideas. Communities of the city, workplace and family all mean arguably more than the single people who get the credit, something The Amazing Spider-man never concerns itself with. New York would self-destroy on its own and Peter is definitely a hands-off type of guy when it comes to grieving families.

For some, the action of either movie might be the only reason to be interested, but both maintain the overall attitude of their respective films. Magic Mike’s dances have a seriousness, an underlying motivation of necessity, that yet does not dull their euphoria-inducing release of energy and pants. It’s in the cleaning up that the reminder of a world outside returns.

No worry of that in The Amazing Spider-man, which pulls on the influence of Sam Raimi and video games, and assembles an odds-and-ends collation of incongruous mouthfuls of noise, served up with an unwelcome accompaniment of James Horner blast. The movie trumpets its ego-driven emptiness with pleasure all the way through to its title. The moniker could be said to have something of a similarity to the adjective-attached name for Soderbergh’s movie, but Magic Mike is a stage name, something that works as a bit of advertisement, but doesn’t stand up when entered into interaction with someone else not instantly enamored. The Amazing Spider-man needs just that in order to work. Magic Mike works through, in its own way, the ramifications of a certain kind of “power” and “responsibility,” and, crazily for today, manages a non-exploitive ending too.