by Sophie Isbister (Contributer)

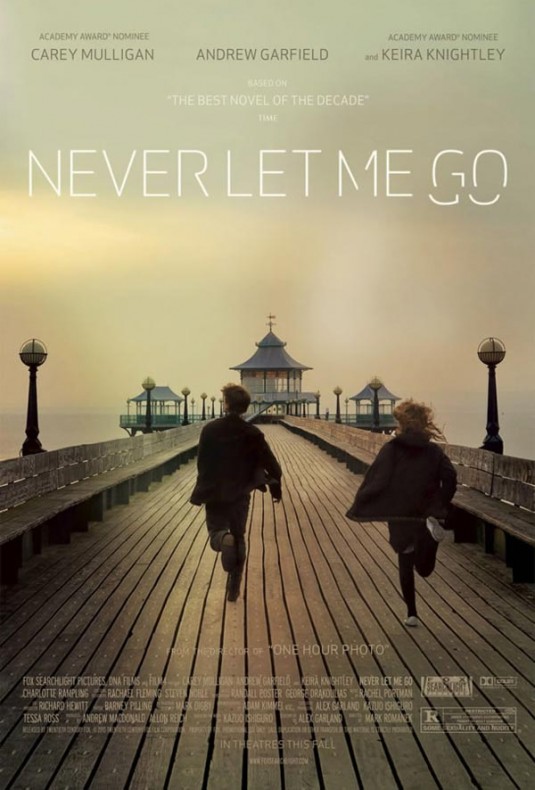

Never Let Me Go, based on the novel of the same name by Kazuo Ishiguro, is a British dystopian drama-romance directed by Mark Romanek, a prolific music video director who took a turn to feature films with 2002’s One Hour Photo. Never Let Me Go employs the same sparse cinematography as Romanek’s other film, but that’s where the similarities end. The film enjoys nuanced performances from Kiera Knightly, Carey Mulligan and Andrew Garfield and had its Canadian premier at the Toronto Film Festival.

Never Let Me Go, based on the novel of the same name by Kazuo Ishiguro, is a British dystopian drama-romance directed by Mark Romanek, a prolific music video director who took a turn to feature films with 2002’s One Hour Photo. Never Let Me Go employs the same sparse cinematography as Romanek’s other film, but that’s where the similarities end. The film enjoys nuanced performances from Kiera Knightly, Carey Mulligan and Andrew Garfield and had its Canadian premier at the Toronto Film Festival.

Never Let Me Go is not your usual dystopia. There are no explosions, no Cormac McCarthey-esque nuclear winters and bleak surrounds. The only indication that things may be awry for characters Kathy (Mulligan), Ruth (Knightley) and Tommy (Garfield) is the tone set by the muted blue, green and grey colours that populate this devastatingly beautiful film.

Initially, we meet the main character Kathy H as an adult, but through her narration we are taken into the past, into her memories. The first half of the film surrounds the characters as children (played by brilliantly-casted child actors who could conceivably grow up to be Mulligan, Knightley and Garfield impersonators), living in rural boarding school Hailsham, in the English countryside. The children sing in unison, never go outside the boundaries of the property, and in addition to learning their three r’s, they role-play interactions that would take place in the outside world instead of actually participating in it.

Through heavy-handed devices, the viewer quickly learns that Hailsham students are “special.” They are living, breathing organ factories, cloned from the otherwise invisible “dregs of society” (prostitutes, vagrants) for the purpose of giving organs as “donations” in their adult lives. For the rich who can afford this luxury, the future painted by the film seems appealing: no cancer, no illness and life expectancies that soar above a hundred years.

Instead of focusing on the broader implications of this political decision on the part of policy makers (where are the civil liberties groups in all of this?), the story accepts the status quo and wisely follows the simple but emotionally-wrought love triangle between the three main characters. Kathy loves Tommy; Ruth and Kathy are best friends, but Ruth is spiteful and jealous of Kathy, so she steals the emotional Tommy, thwarting a very real love that could have blossomed between Kathy and Tommy.

The three children grow up together and turn into young adults. They are moved to The Cottages, a place where they will live with other youth like them. Clad in droopy wool clothing, they make for a sad looking lot, and plenty of brooding whilst looking out windows at the rainy English countryside ensues.

The central question of the film is modest. Simply, are these children, who were created in a lab, actually human? Are they able to love? This question has already been answered by civil society in the film, and is evidenced by the way people from outside Hailsham and The Cottages treat the children, as well as by the casual grace with which the children accept their place in life. Delivery men shy away from them and treat them like aliens. The children don’t get real toys; instead, they buy junk (broken dolls, old cassette tapes, dirty teddy bears) with tokens (tiddly-winks) at periodical “toy sales” that are put on by school administrators. When, as youth, they venture into town in their odd attire and have no idea what to order at a diner, people stare. The film shows passionate and complex emotions between the three main characters, slamming the viewer with the sad reality of the lives of these protagonists.

Ten years after they leave The Cottages, Kathy is working as a Carer (someone who provides comfort to the donors) and waiting to begin her own donations. She sees Ruth at the hospital. Ruth is on her second donation and in very poor health, but, determined to redeem herself for her childhood spite, she convinces Kathy to reconnect with Tommy. Following their reunion, the new couple sets out to find some answers to an oft-whispered rumour from Hailsham, the rumour that if two people were “truly in love,” they could put off their donations for a few years, and live together like a “proper couple.”

This stunning film is a reminder that perhaps the worst dystopia is the one that looks civilized, yet is rife with institutionalized cruelty. The film reminds society how far we could go in our quest to achieve perfection and long life, but more importantly, the short but blissful romance Kathy and Tommy share with each other reminds the viewer to take and enjoy the small amount of happiness that is given in our tumultuous lives.