By Michael Scoular (The Cascade) – Email

Print Edition: February 6, 2013

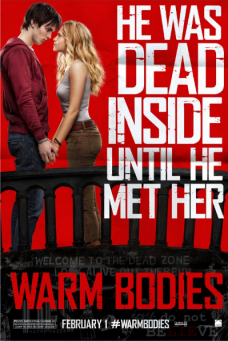

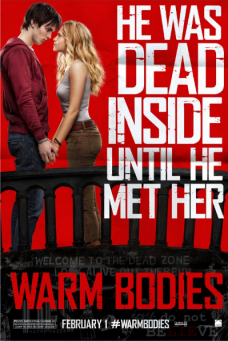

Referencing such revered classics on the subject as Romeo and Juliet (that puts it the esteemed company of, among others, The Twilight Saga: New Moon), Warm Bodies is a movie all about the changing power of love. Or so it claims. It is certainly a definition of love, but that it is one of change, of revolution against apocalyptic desolation seems suspect from the internally-germinated beginning.

Referencing such revered classics on the subject as Romeo and Juliet (that puts it the esteemed company of, among others, The Twilight Saga: New Moon), Warm Bodies is a movie all about the changing power of love. Or so it claims. It is certainly a definition of love, but that it is one of change, of revolution against apocalyptic desolation seems suspect from the internally-germinated beginning.

That this comes from director Jonathan Levine—of the similarly voiceover-monologued 50/50 and its misguided rerouting of cancer pathos into sex shaming and frat humour—makes any kind of message of love, or even a less self-important play on a familiar story of love, as it might want to be taken, something best rejected.

R (Nicholas Hoult) is a misunderstood adolescent male (actual line: “Am I the only one?”) who, if you could only hear his inner thoughts (we can, and will, for the near entirety of the movie), would see what a great, funny (the ironic, detached kind), heroic guy he can be. The genre overlay on this romantic play on romance means our protagonist is a creature of the undead, where undead means a slightly paler shade of skin, visible veins like a flaming neck tattoo, scars ever-so carefully placed, and deep purple lips.

Warm Bodies, like trailer accompaniment Beautiful Creatures and The Mortal Instruments, is indebted (at least financially) to the Twilight series – the twist with this one being comedic commentary and being uprooted from the banalities of home-school routine.

But what was arguably the best thing about the Twilight series in that setting was the utterly mundane conversations and interactions—that this movie series was putting non-starting words and awkward pauses up on the screen and either asking for absorption into Billy Burke’s grounded turn as Bella’s dad and the tension therein or provoking laughter—what is real from a distance becomes absurd. Levine writes self-referential zombie observations into R’s dialogue (joking about how zombies walk slow, R says “Man, we sure walk slow” – Levine’s range of undead imagination suggests a few watches of Shaun of the Dead and I Am Legend) as a sign he’s above it all, but none of it is nearly as gloriously ridiculous as Taylor Lautner de-shirting to dab a wound or Robert Pattinson skulking and mumbling – Warm Bodies tries to be new (conventionally) at something its original imitation already did.

What always remains is that Warm Bodies is from a deliberately close-minded point of view – one that sets up love as something gained after conveniently meeting and sticking together through lies, heroic presentation three or so times, and counting on the illogic of a script (introduced as a resistance fighter, it takes all of five minutes before Julie (Teresa Palmer) is deprived of all agency). Before Warm Bodies shifts into chase-action partway through, there is the all-important falling in love, but love is here something gained through deceitfully-planned captivity and knowing the way to a heart is through a record collection, alcohol and a convertible – love as Stockholm syndrome and the kind of nausea-inducing object-like- becomes-love that underpins “romantic” “comedies” like This Means War.

If there’s a halfway-redeeming quality of Warm Bodies, it is Javier Aguirresarobe’s cinematography, smooth, serviceable and clear, it contains echoes of his previous work (not coincidentally, New Moon and 2011’s Fright Night) while also standing as a mark of how, while in projection there is an easily perceptible distinction, the actual use of film versus digital means for movie production is now no longer a question of image quality. With Warm Bodies, and the definitions of love it carries and repeats from other like-minded voices, there is a similar crowding out – when everything about this movie shows love being an awakening force, the great life-giver, but its practice being one of possession, of use and interchangeability, a confusion of love and the meanings worthless directors like Jonathan Levine give the word naturally follows.

In one of Levine’s most revealing lines, a leader of a group of men exclaims “bitches, man” as joke relief to console poor, poor R. As Levine mostly shows them, damsels in distress rarely have much to say (certainly not as much as his protagonist). One sure sign of directorial ability is in the shoddy handful of lines and eyerolls given to Analeigh Tipton, capable of more than shown here, as in Whit Stillman’s excellent Damsels in Distress, a clear-eyed response to 20-something lovelessness masquerading as love and its resulting depression.

Dancing through fantasy, a (kind of) vampirism, the question of when it’s okay to send drinks over to a table, and dialogue that isn’t regrettable to hear running through a human’s head, Damsels in Distress is everything Warm Bodies is not: concerned with beginning the practice of love, rather than its deformed imitation.