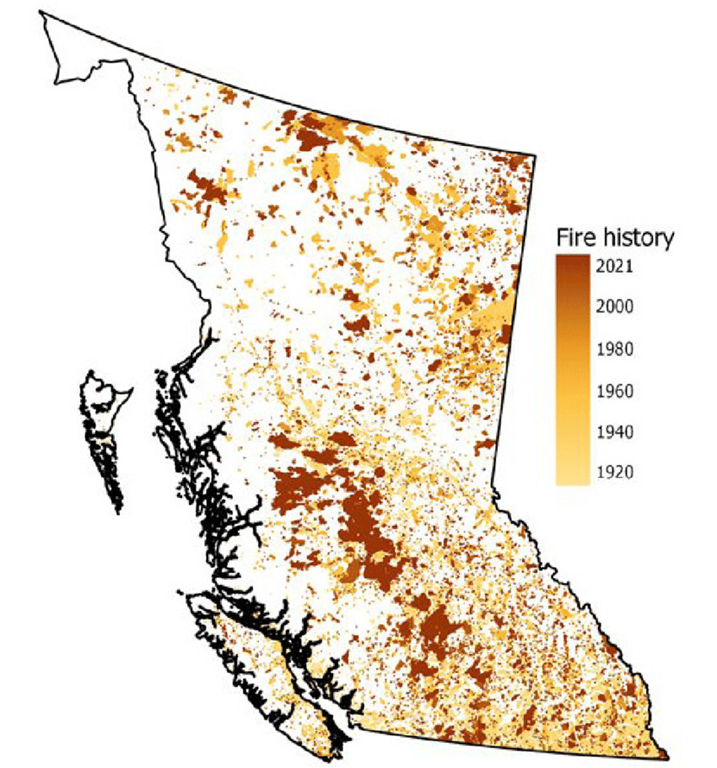

The summer of 2023 was the most destructive wildfire season yet in Canada, burning a total of 16.5 million hectares from 6,132 fires. Overall, an average 2.5 million hectares of land is burned in Canada each year. With this year’s season of wildfires rapidly approaching, experts can easily predict the effects on humans and wildlife. The threat and danger of wildfires is an ongoing epidemic.

Despite how damaging wildfires are to communities and the environment, there is room to prepare for them. Prescribed burning — a colonial adaptation of a cultural practice long used by Indigenous communities in Canada — can be beneficial in maintaining future generations of forestry.

The Cascade spoke with Stefania Pizzirani, associate professor and program chair of Planning, Geography, and Environmental Studies, about the devastating B.C. wildfires.

“These megafires are really what we’ve seen here in B.C. It’s these seemingly out of control fires that you cannot stop. Those are the ones that are very much on the radar of a lot of professionals,” Pizzirani said. “The major reason we are noticing fires more often is that we are living in forested areas, and of course in Canada we have a lot of forests.”

Pizzirani explained that the areas of the world that large populations of people reside in are hazardous and susceptible to fires, floods, earthquakes, and tornados. That means it is inevitable that naturally occurring events will have disastrous impacts on humans in vulnerable areas.

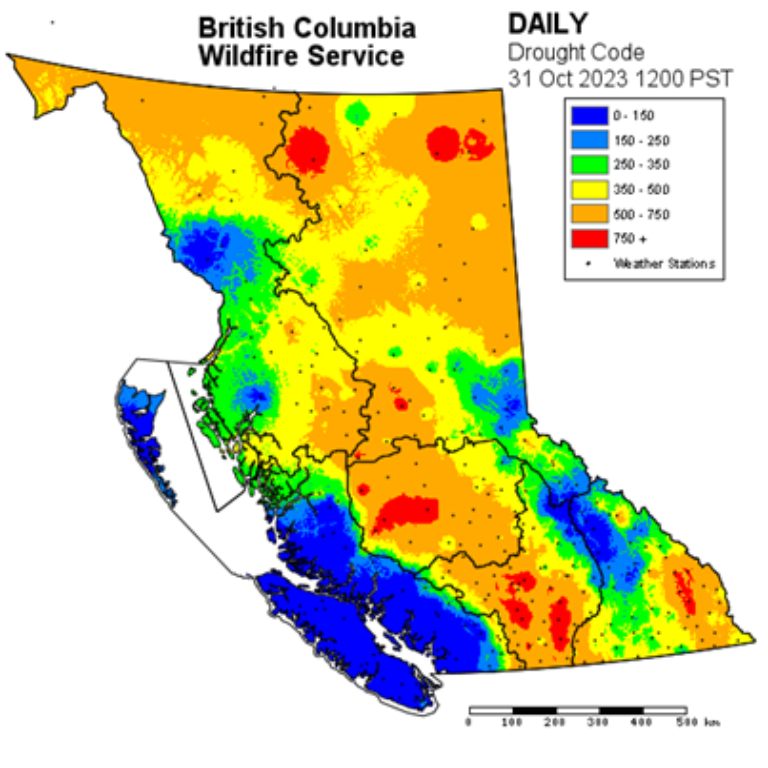

As a society, humans are one of the main causes for these “megafires,” said Pizzirani. Something like “flicking your cigarette out the window” can be incredibly damaging. Many fires are started by lightning, too, but climate change has also played a huge role. “We have a lot of fuel for the fires, and we have warmer winters, so pests can live throughout the winter now instead of being killed off because of low freezing temperatures.”

Pests like pine beetles, which are a native species, have “killed millions and millions of trees,” said Pizzirani. “There’s not just trees that are alive and could maybe fight off a fire or withstand a fire, they are dead and dying trees, so when a fire comes along, it’s the perfect condition for a megafire.”

Fires are “a normal part of our ecosystem,” said Pizzirani, explaining that forests often need heat to produce new growth by getting rid of the old foliage underneath. “They require fire to clear out the underbrush, to form new seedlings, and to regenerate a new regenerative layer of forest, instead of just being dominated by one single forest canopy.” She added that some species are “completely adapted to fire,” such as the cedar trees that grow all around B.C. “Burning also creates a lot of fertile soil.”

Canada’s connection to our forests has made fire suppression “the main objective for a hundred years,” said Pizzirani. “It’s sad when we lose them, but we’re not so much losing the forest as we are keeping it in balance; keeping it protected.”

The use of cultural burning and prescribed burning is a method Pizzirani has begun to see used more frequently. She explained, “Indigenous communities across Turtle Island have done prescribed burning and cultural burning for millennia. It was in tune with seasons; it was in tune with herbivores and the other animals that were coming and going.”

Pizzirani continued,“It was definitely seen as a method of collaborating with their environment to facilitate safety and all the necessary components in the system. So, controlling grasses for example, starting smaller fires earlier in the spring prevented enormous vegetation growth in the summer leading to massive fires by the fall.”

Despite this, fires are inevitable and cannot be completely prevented. “It is impossible to not have fire. It’s impossible and we shouldn’t aim for that. It is like trying to stop the tides from happening,” she said.

“As a society, I think we need to re-educate ourselves to unlearn and relearn where it is used and where it is helpful.”

Veronica is a Staff Writer at The Cascade. She loves to travel and explore new places, no matter how big or small. She is in her second year at UFV, pursuing the study of Creative

Writing.