By Martin Castro (Contributor) – Email

Print Edition: March 11, 2015

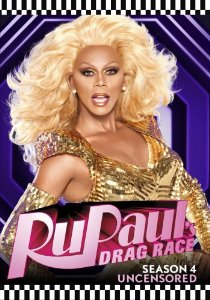

Jim Daems, a sessional English professor at UFV, recently published a book titled The Makeup of RuPaul’s Drag Race: Essays on the Queen of Reality Shows.

Daems has published four books, as well as numerous articles focusing on literary figures such as Edmund Spenser, John Milton, and J.K. Rowling.

You’ve published a number of books and papers on 17th-century Irish literature. You’re particularly interested in authors like Spenser and Milton, and also in representations of Ireland and gender. What is it about this period and these authors and topics you find so interesting?

Coming here [to UFV] and starting as an anthropology major, and doing my English [requirements], I got carried more to the English side of it. In terms of gender, I’ve always been interested in gender. It was a weird fixation of mine as a kid.

Seemingly out of the blue, you drop this new project focusing on RuPaul and reality shows. What prompted you to pursue this drastically different topic?

It’s kind of an offshoot. I mean, it’s different than gender theory in 16th- and 17th-century texts, but the interest is sort of there. You have time during office hours, so you sit there looking through the calls for papers. It was a Canadian publisher — I can’t remember which — doing a pop-culture series, and they wanted proposals on reality TV shows, so I sent one to them, and they didn’t get taken in there. And as of the New Year, I’d been looking for something to do.

So the book focuses on what aspects of reality shows? And what aspects of reality shows interest you?

The book looks specifically at RuPaul. There are eight or nine contributors, and they all entered their own angle on it. All of them looking at what the standard conventions are how you have certain types of reality shows: you have the competition show, Survivor. You have the makeover show, whether that’s a home makeover or a [personal] makeover. In terms of reality TV as an overall genre, RuPaul’s been able to kind of pull bits of [all those types] into a show on drag. But then also, obviously, in terms of gender and queer theory.

How do you make a show on drag accessible to different viewers?

Last season, one of the big controversies was a trans controversy. There was one challenge, where you’re supposed to guess, from kind of a close-up of somebody’s mouth whether they were male or female. Anyway, some trans [people] kind of complained about what he was doing. So, some of the essays look at that and, because it’s America’s Next Drag Superstar, a lot of Puerto Ricans are on the show, so they’ll look at it in terms of Puerto Rican identity … What sort of drag is [RuPaul] favouring? And if you speak in broken English, then does that work against you?

Were you interested in reality shows, or had you seen reality shows before you started work on this RuPaul book?

Yeah, it’s kind of hard to avoid running into reality TV. What interested me is the fact that he is taking a genre that’s kind of running itself out, and is really closely defined or categorized by sub-genres, and was able to kind of pull that into something new. He’s kind of running out of steam, so this next season will be interesting; we’ll see what he can do with it.

Have you found any connections between topics expressed in 17th-century literature and contemporary reality shows?

No, what’s interested me mainly is just the way that gender works. For me it’s always, how do they see gender? As being something essential, or is it something we make up? Drag kind of shoots the whole thing to pieces. We can go back to the 17th century and look at William Prynne’s Histriomastix, and there’s this problem of, “Does dress make the gender?” If you dress like a female do you become a female? And if a female dresses like a male, does she become a male? So there’s that sort of tenuous kind of link because it’s in a different context.

How do you go about researching reality TV shows?

Breaking them down into different sub-genres, because they have a different focus. A lot of them, say, are about self-improvement, you know makeover-type shows; competition shows aren’t. It’s hard to break them apart into those genres. You can look at it in the meta way: What is a reality show? And you can question in that kind of sense, how real is it? They all involve scripting; they’re all choosing contestants because they think there’s going to be conflict. If you’re going to put them into Big Brother, you want conflict. So there are a lot of big questions. What attracts me is the nature of drag itself, and what you have in terms of reality, because what does drag say about reality?

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.