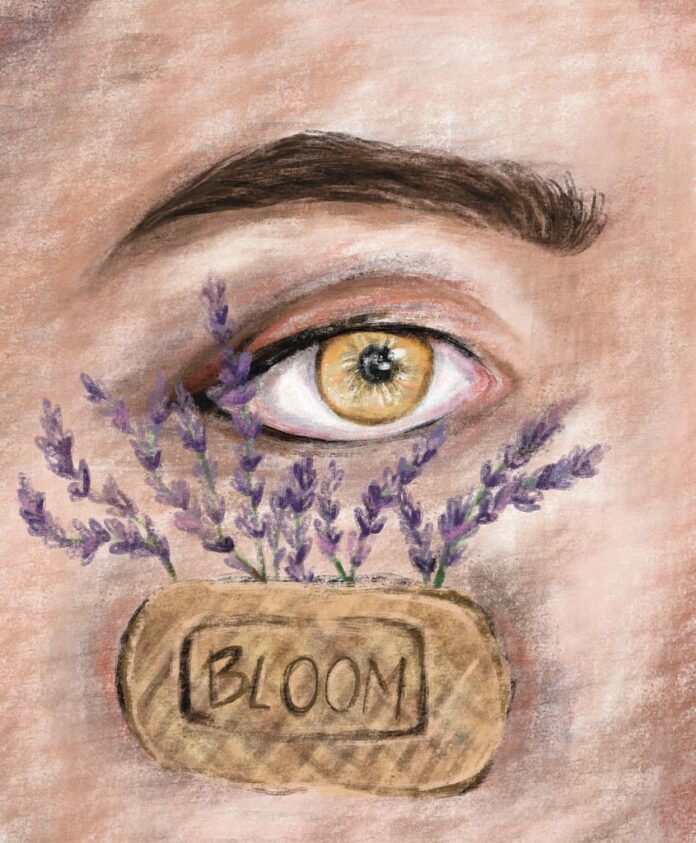

Dear late bloomer. My name is Shivalika, and it’s a pleasure to meet you. Every late bloomer’s story is different, but we all share the pain of feeling inferior to our peers, and shame for being “behind” in life.

I am a 27-year-old student sitting in a class of majority 18-year-olds, relating to conversations that start with “When I grow up,” and I do it shamelessly.

My late bloomer journey began in 2016 when I dropped out of Simon Fraser University due to health concerns, as the lines between ambition and self-sabotage began converging. Not only was I the first in my family to pursue a Bachelor’s degree at a Canadian university, but I was also the first in my family to drop out of it.

This ushered in a new chapter of my life, the great disappointment. It wasn’t the multiple suicide attempts, car accidents, or losing touch with reality that ate me alive. It was the overwhelming feeling of inadequacy which condemned me to a vicious cycle of lasting denial and fleeting acceptance.

I was diagnosed with borderline personality disorder (BPD), premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD), major depressive disorder (MDD), and generalized anxiety disorder (GAD). All of which made me feel like Thanos, collecting acronyms like they were infinity stones. As a psych student at that time, I was painfully aware of the very real implications of those “infinity stones.” However, to my family, those “stones” were just labels with fictional meaning.

I fought my ailments, societal and familial expectations valiantly to make sure I remained on this earth long enough to feel the sweet reprieve of respite. It took me four years to feel an inkling of relief. However, even with all that fight in me, I felt like a failure — a self belief that was made worse by constant comparisons to my peers. From weddings to helping their parents pay the mortgage, from beginning new careers to post-secondary graduations, everyone’s success felt like my personal failure. No matter how hard I tried, I couldn’t fix myself enough to “catch up” to them.

Taking tumultuous years to accept my disabilities, I learned the hard way that human entitlement to control our lives is an illusion meant to make us feel secure in our existence.

In light of my newfound acceptance, my first task was recognizing my high ambition and smaller than average energy tank; here, size mattered. I discovered that gaining education and experience was something that I was still enthusiastic about. So, at the age of 27, with some post-secondary credits, job experience under my belt, and the support of my healthcare providers and loved ones, I decided to go back to school to try once more.

The thought of returning to academia was easier than its execution. I couldn’t shake the feeling of being a pathetic ancient relic who was 10 years too late in pursuing her education. However, by putting my thoughts on trial, rationalizing my fears, and viewing my fragmented experiences as pieces of a successful future rather than shards of a shameful present, I effectively provided myself with the grace I needed to return to school, because I had a goal.

I was well acquainted with myself enough to know that my original desire to become a psychologist was not compatible with my chronic disabilities. So, I changed it. Now, my goal is to become a communications specialist; I want to be the person who forms connections and communicates with others for a living.

For my academic return, I was mindful of my limitations and decided to take one class per semester until I am ready to handle more. I realized that there is no shame in taking life one step at a time, and that the continued steps taken on the path to success are just as important as the last. With that mindset, I took the next step, which was asking for help. To do that, I registered with the Centre for Accessibility Services (CAS).

Currently, CAS provides me with tailored in-class accommodations that work in tandem with my disabilities, making it easier to be present in an overwhelming classroom environment. Taming my pride and unleashing my humility by reaching out to CAS was my way of practicing self-care, as I now know and accept that, for me, railings are necessary while climbing the staircase of accomplishment.

My self-acceptance is not synonymous with a cure. I still struggle, as I’m painfully aware that life is not a series of compounding or linear progress. However, now I’m equipped with the knowledge of recognizing my limits, nurturing my strengths, and keeping in mind that everyone is different. My destination demands a slower pace in the journey, and that’s absolutely okay.