Slaves Days in Chilliwack during the 1950s and 1960s

Twice a year, Chilliwack teens and teachers would partake in a school spirit day known as “Slave Day.” On the first day, boys got to own a fellow girl student. The next day, girls would be the fictitious slave owners. Teachers arranged imaginary slave auctions, where students would be “sold off” to do domestic chores and humiliating acts, which caused unnecessary harm to the pupils. The students and staff that wrote their weekly school summaries for The Chilliwack Progress were hyper-aware of the disturbing nature of the festival, yet they did it anyway. These rituals occurred during and long after the civil rights movement, so how did the Fraser Valley not get the memo? Did they not learn nor care about the intergenerational trauma of Black people and Indigenous people across the globe? For several decades, Chilliwack Senior High School (CSHS), Sardis Senior Secondary, and other small schools seemed to be stuck in a bigoted time-warp.

“For several decades, Chilliwack Senior High School (CSHS), Sardis Senior Secondary, and other small schools seemed to be stuck in a bigoted time-warp.”

I discovered the following newspaper clippings in a history course, Local History for the Web (HIST 440). The only parameter I was given by the professor was that the final paper must be related to the history of education and schools in the Fraser Valley. Amidst the early period of COVID-19, I began to search the local digital archives. Since I had just finished my essay “Underneath or Covered in Soot: The Ku Klux Klan and Ritualized Racism in Abbotsford during the 1920s,” I was determined to uncover more hidden histories of hate. I did not expect to find a multitude of newspaper clippings of children pretending to be slaves.

Many readers may find the historical descriptions below uncomfortable. Historians like Cheryl Thompson and Emilie Jabouin insist institutions across the nation must uncover evidence of racism to dismantle historically rooted prejudices. As a public historian, I feel a responsibility to share my findings with my community and to guide readers through feelings of moral shock.

There is some literature about slave auctions as a form of working-class entertainment. But historians have overlooked primary sources found in public schools. The only group that seems to be interested in this phenomenon is online journalists. As far as I am concerned, there seem to be few historians that are interested in this ritual. This article will take a multifaceted approach to deconstruct the implications of “Slave Day” in Chilliwack high schools. To do this, I refer to historiographies of slavery in Canada, blackface, and other forms of plantation entertainment.

Slave Days: Teens reenacting fictitious slave auctions

So far, the earliest record of “Slave Day” in Chilliwack is in the Feb. 6, 1957 issue of The Chilliwack Progress. In bold text, the column reads: “Slave Day! Well now, this is a weird idea.” Let’s break this down: it is a “weird idea,” because slavery did occur in the so-called “Great White North.” Since Canada has a short growing season, plantations were not built in this nation. Instead, enslaved people and indentured servants in Canada laboured in the “big houses.” The Chilliwack Progress continued to state that “the Y-teens are going to sell tickets to the boys one day: the next day one of those tickets entitles any boy to enslave any girl to carry his books, do homework or practically anything — during school hours.”

A later entry on Feb. 20, 1957 expands on the tasks the liminal slaves accomplished: “As for what the boys made us do on that fatal Thursday of last week — we cleaned out lockers, covered books, sang crazy songs, did crazy things, ran errands, helped the janitors, wore the boys’ coats around and generally were the big joke of the week.” Here, school children mocked the way enslaved labourers would be tasked with domestic chores to preserve the manor. Another odd practice in this ritual is that children “sang crazy songs.” Underneath the moonlight, enslaved peoples would gather around in a ring and sing cautionary songs of white people or other life experiences. This mockery of singing while performing chores is disturbingly reminiscent of how actual enslaved people spent their leisure time.

“school children mocked the way enslaved labourers would be tasked with domestic chores to preserve the manor”

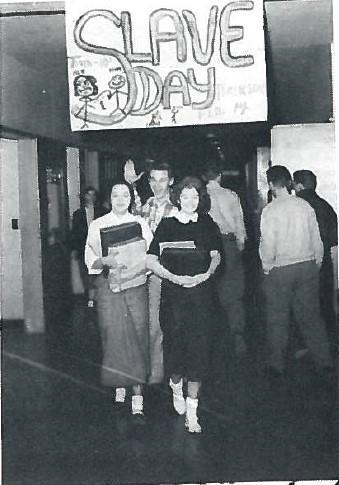

The only retro picture of “Slave Day,” so far, is in the 1956–1957 CSHS yearbook. In this photo, there are two young girls holding books; behind them is a very eccentric young man. Above the crowd of students is a sign that reads “Slave Day.” Underneath the “S” is a feminine stick figure with a rope around her neck; at the other end of the rope is a menacing stickman. This crude, immature drawing illuminates some of the subconscious understandings of slavery. There are two interpretations of the rope. Firstly, this could be a leash that represents obedience and ownership over young girls. The more disturbing interpretation is that this rope is a noose, to symbolize lynchings of enslaved people of colour. Historians argue that blackface and other forms of colonial mimicry in the early 20th century was a part of “plantation-themed entertainments.” Robin W. Winks posits in his book The Blacks in Canada that “many small Ontario towns … would regale youngsters with tales and songs of slavery down on the old plantation.”

In the Jan. 29, 1958 edition of The Chilliwack Progress, it was announced that for the “first time there has been a slave day” at CSHS. There were two of these school spirit days set up: one for the boys and one for the girls, so every child had a chance to be both a slave and slave-owner. This event was planned for Jan. 31 by division 95; here is the written summary of the event: “at 8:30 am girls in all grades who have previously bought tickets for 15 cents each may hand these tickets over to different boys, commanding them to carry out whatever tasks the girls choose. Boys — the slaves — have no choice but to obey but may refuse to do two things at once. When the task is completed, the boy returns the ticket to the girl.” The second event, planned by the Y-teens for the schoolboys, wrote a list of possible tasks that could be done, such as “carrying books, cleaning out lockers, covering books, polishing shoes, holding the water fountain faucet, and all sorts of other things.” Theater historians Joseph Roach and Jason Stupp state that white people playing as slaves is a form of disembodied history. Any historical reality of slavery in Canada is “emptied” by these performances. However, there is a history of white people using slave-trade auctions as entertainment venues.

There is a discrepancy between both the 1957 and 1958 news columns. The 1958 article declared the festival occurred for the “first time.” But according to the archives, this is false. The 1957 article seems to be the first written record of a “Slave Day” in Chilliwack. This could be a miscommunication between local editors. It is also plausible that this could be the start of the smoke and mirrors around “Slave Day” in Chilliwack. Although the concept of play-pretend slave auctions was presented as a new-fangled pastime, historically, slave auctions have been a form of entertainment.

Anthony Pinn, professor of African-American religion and constructive theology, theorizes that slave auctions were a ritual whereby white people “made” African Americans into a “historical material.” Both slave purchasers and those that could not afford to buy human beings watched these auctions as spectacles. Historian and academic Saidiya Hartman suggests, “Those observing the singing and dancing and the comic antics of the auctioneer seemed to revel in the festive atmosphere of the trade and thus attracted spectators not intending to purchase.” This mixing of different social classes created a white “racial fraternity and privilege” based on plantation imagination. This obsession with human ownership “through the ritual transitions of the marketplace” created a space where reality and fantasy merged, where white people transcended class, played a prescribed role, and maintained white supremacy.

Why then?

For many nights, I stewed over the possible decade when “Slave Day” began. The late fifties seems like a perplexing time for all of this to start; the civil rights era was brewing over in the States, segregation was slowly breaking down, and slavery had long been abolished. During the writing process, I asked myself constantly, “why then?” It wasn’t until I submitted my first draft of my paper for HIST 440 that I found another clue. One late night, I watched the Youtube video “Defunctland: The History of the Terrifying Splash Mountain Predecessor, Tales of the Okefenokee.” In this twenty-minute documentary, Kevin Perjurer summarises the creation of Disneyland’s roller-coaster Splash Mountain, based on the controversial film Song of the South (1946).

According to Perjurer, Walt Disney was inspired by Joel Chandler Harris’s novel Uncle Remus (1881). As a young boy, Harris avoided the Civil War and lived on Joseph Attison Turner’s plantation in Atlanta. During this time, Harris listened to African people enslaved by Turner, who told him folklore that taught life lessons using animals. Perjurer notes that “Harris latched on to these stories and even more so the storytellers; he felt that he had a connection with the enslaved people because of the hardship he had endured for the way he looked and sounded despite, in reality, their plights being incomparable in every sense of the word.” Later, Disney acquired the film rights to create a live-action movie based on the racist book. In Song of the South, Uncle Remus (played by James Baskett) gives Johnny (Bobby Driscoll) life advice through the southern landscape of Okefenokee, accompanied by cartoon characters Br’er Rabbit, Br’er Fox, and Br’er Bear. Shortly after the film was released, progressive Americans were outraged at the “fortification of the South and the master/slave relationship.”

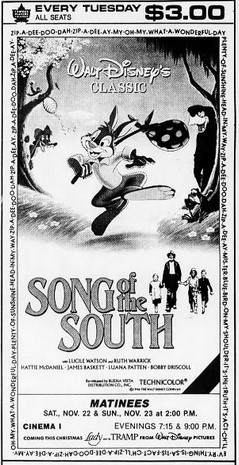

In 1956, Song of the South was re-released in Technicolor for theatres with no backlash. A year later, Chilliwack Senior High School had its first “Slave Day” celebration. I believe this is not a coincidence. In this reboot, advertisements focused heavily on the anthropoid characters rather than the live-action portions. This marketing campaign mass-produced records, marble games, Golden Press books, and a Br’er Rabbit’s Scotch Tape Contest to win a trip to Disneyland. Apparently, there was also a “Song of the South Half Sheet School Poster” meant for classrooms. It is unclear how much of this memorabilia was available in Canada.

Although there is no record that Song of the South played in Chilliwack during the 1950s, there was a showing of the movie on Sept. 12 and 13, 1947. This proves that the community would have known about Song of the South. This musical was re-released several times in Chilliwack throughout the latter 20th century. During Christmas week of 1973, the Chilliwack Paramount Theatre held a “The Purr-fect Zip-A-Dee-Doo-Dah Fun-fest,” which featured showings of both The Aristocats and Song of the South, (oddly enough, both films depict racist imagery). On Nov. 22 and 23, 1986, Song of the South was shown yet again at the Chilliwack Paramount Theatre.

Based on these findings I have two suggestions: firstly, “Slave Day” was inspired by the Song of the South’s misrepresentation of slavery. Secondly, each reboot revamped the relevancy of the school spirit day. Each decade that the film was re-released, it reenforced false histories of slavery and white nostalgia. Adaptation theorist Linda Hutcheon suggests the constant rebooting of plantation fiction allows for the “ubiquity and longevity of adaptation as a mode of retelling our favourite stories,” What is dangerous about this type of storytelling is that it creates what Tara McPherson refers to as “cultural schizophrenia.” This type of media conveys “The Deep South” as both “the site of the trauma of slavery and also the mythic location of a vast nostalgia industry.” Stories like Song of the South fixate on certain aspects of the south to heighten nostalgic memories and feelings without revealing uncomfortable histories. This is one of the many reasons why “Slave Day” was so extremely toxic for teens. The history of slavery and intergenerational trauma should never be taught through games or poorly written animated movies.

“Sounds absolutely terrible, doesn’t it?” The 1960s

The Chilliwack Progress used sarcastic and belittling language to address the slave children. In the Mar. 29, 1967 issue, Rhiannon Jones wrote a summary of the spring festivities at Sardis Senior Secondary. Jones advertised “Slave Day” in her column: “Grade 12 girls, beware! Slave Day is approaching. On April 6th and 7th all Grade 12 girls will be rounded up to be herded into the gym to be auctioned off (sounds absolutely terrible, doesn’t it?).” Two themes jump off of this page: this festival is a parody of white slavery and a mockery of actual slavery. The phrase “It sounds absolutely terrible, doesn’t it?” needs to be unpacked. Yes, it does “sound terrible,” because slavery actually occurred. People in 1967 would have been fully aware of slavery and the civil rights movement. However, the subtext of “it sounds” suggests it is hypothetical, that slavery in Canada “sounds” terrible but didn’t really happen. This sentence awkwardly acknowledges that there is a history of slavery and how “it sounds terrible,” yet it does not mention anything about slavery. There is an alternative meaning for this text: it has a sarcastic tone which suggests it is meant to be a joke. White working-class people use racist humour to make themselves feel superior. It could also be a way to “replicate the romanticized social order of slavery.”

On May 7, 1969, there was yet another “Slave Day:” “This year the boys were slaves and for the price of a ticket the girls had sole command of them, within the limit of the rules. I saw quite a few boys trying to do song and dance acts and I even saw one boy crawling around on his hands and knees calling for his ‘mommy.’ All this went on during noon hour but there was still some action in classes (at the discretion of the teachers). Any boy who did not comply with the girl’s demands or any girl who gave impossible commands could be booked into kangaroo court….”

This entry follows a similar pattern: It occurs during the spring; requires a fiscal entry to participate/own a child; one student of the opposite sex owns another student temporarily; acting slaves would be forced to sing, dance, and clean. However, this entry introduces new information. The festival occurs in three parts: There was a slave auction, slave and master role-play session[s], then a fictitious court to serve punishments. It also mentions that some children refused to perform certain tasks…. Why would they refuse when this is a school-wide spirit day?

The clipping continues: “My sentence was to eat a peanut. That may sound easy, but it isn’t…when you must eat the shell also. Someone else had to run around the gymnasium twice and another person had to keep yawning until someone else could be induced to yawn and so the sentences ran on.” Children who either refused to participate or were too demanding were put on a mock trial. Two classmates then choose punishment: eating challenging foods, mental manipulation (yawning), and forcing physical actions.

Before the emancipation, actual slaves were physically, sexually, and mentally abused or murdered for either their slave master’s amusement and/or to evoke a sense of fear in other enslaved peoples. Those who could not forage on the manor were forced to eat “pot likker,” a vegetable-based broth. Many enslaved children were malnourished and had “shiny bodies and extended bellies.” The news confessional closes, being grateful the festivities were over: “The two days were a tremendous success, but I am glad slave day comes only once a year.”

Okay, now what?

“In June of 2020, several BC news outlets exposed the story of Rosedale Middle School’s Slave Day festival in 2009.”

Newspapers.com, the digital depository for The Chilliwack Progress, has 55 entries on “Slave Day.” These newspaper clippings range from the 1950s to the 1990s. Since there is no historical literature on fictitious slave auctions in public schools, there is a lot to uncover. All of the articles above were written from the perspective of white children who did not realise they were partaking in colonial mimicry. This play-pretend festivity has caused controversy within the community. In June of 2020, several B.C. news outlets exposed the story of Rosedale Middle School’s “Slave Day” festival in 2009. A photo of the “Student Auction” page in the Rosedale Yearbook was posted on @BlackVancouver’s social media account. Underneath some photos of students, the caption reads: “During Rosedale’s 2nd annual “Slave Day,” grade 8 and 9 Leadership students were auctioned off. In total, they were able to raise over $450.00 for our school. Rosedale students could buy slaves… [who] carried books, wrestled, dressed in crazy costumes, committed outrageous stunts to please their masters and the crowd.” After the backlash, the superintendent of the Chilliwack school district wrote an official apology letter. One key phrase from the letter is the following: “As a school district, we don’t have all the answers. We make mistakes. And we need to learn from them.” If this statement were true, the school would have done their research. All it took for me to uncover these stories was to search “Slave Day” in the digital archive. Pretending like the school district “didn’t know” contributes to the legacy of white supremacy and settler colonialism. The event lasted several decades in Chilliwack schools; how could anybody not notice that? Let’s not pretend to ignore racism.