A Eurocentric sport, countries like Germany, Italy and Austria dominate the luge podium. The first international sledding race was held in Switzerland in 1883, with the International Luge Federation founded in 1957. Luge was introduced in the winter Olympics in 1964 and there are four categories lugers can compete in at the Olympic games — men’s singles, women’s singles, doubles, and team relay.

Canadian lugers made their Olympic debut in 1968. The Canadian Luge Association, a not-for-profit organization, recruits and develops Canadian athletes to compete in the winter games. They are funded by the government of Canada, Canadian Olympic Committee, and Own the Podium. Thanks to the development of Olympic tracks in Calgary and Whistler for the 1988 and 2010 winter games, a new generation of athletes was allowed the chance to develop their skills and reach for gold.

The objective of the luge is quite simple: feel the rush of life in you and be the fastest one to complete the track without dying. While in theory, the sport of luge is “simple” enough that children can do it, as children as young as eight can learn the sport, luge is no joke. Sliders can reach speeds of up to 145 kilometers an hour.

Luge is a time-based sport and just a few thousandths of a second can make the difference between silver or gold. The race consists of four runs by each athlete. The total time of each run is tallied up and the luger with the fastest overall time is crowned the victor.

The equipment for luge is a rather short list, with the most technical piece being the sled. The sled is designed to be as fast and safe as possible. A single sled usually weighs between 21–25 kilograms and a doubles’ sled can weigh up to 30 kilograms. The racer slides lying down feet-first and steers the sled by shifting their weight with their shoulders, calves and abdominal muscles.

The sleds are monitored closely before and after each run. The sleds are weighed and examined by officials, so no alterations, such as warming the sled’s blades for a faster slide, can be made. If either a sled or an athlete fails one of these checks, they and their team are disqualified.

A luger’s main source of protection is a helmet with a face shield or visor, and a neck strap to support their heads against the G-forces felt when going downhill. Racers have special “booties” that help keep their legs and feet strapped to the sled, as well as help steer the sled. The final unique piece of equipment for luge is a pair of spike gloves that help grip the ice at the start of their runs.

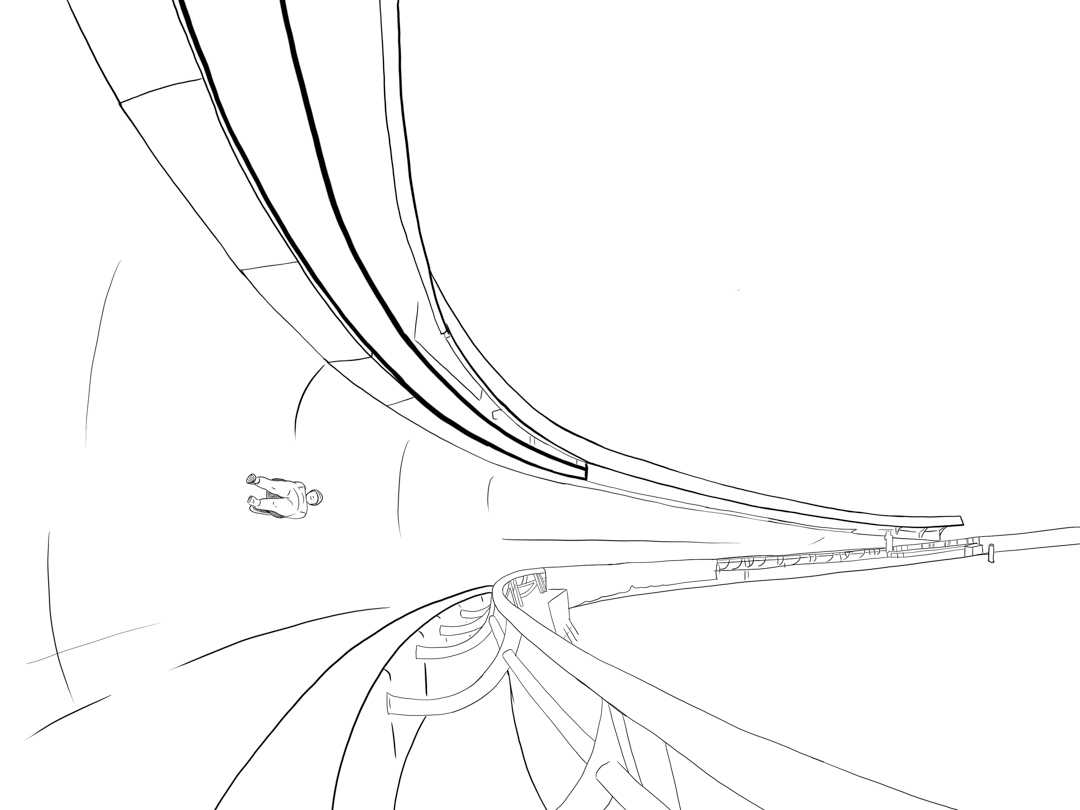

Each luge track is slightly different and provides different challenges for racers. Some tracks are faster than others, some have trickier turns, and the overall length changes too. Each corner and turn on the track is numbered so safety crews know where an accident is located, as well as making it easier for spectators to follow the racers. The Yanqing Sliding Center in Beijing is the longest track in the world, with a full 360 degree corner. The track will be used for the sliding sports of luge, bobsled, and skeleton.

Trinity Ellis:

Trinity Ellis:

Trinity Ellis is a 19-year-old World Cup competitor from Pemberton, BC. She has been competing internationally since 2018. Ellis graciously agreed to talk with The Cascade while she was in Germany on the World Cup circuit.

Ellis came in 14th place on Feb. 8.

You got a head start learning luge as you grew up so close to Whistler. What drew you to the sport at such a young age?

I got my first try [at luge] during a field trip, actually. Living so close to Whistler and the track, I got the opportunity to try it and I just fell in love with it right away. I loved the speed and the adrenaline and just the whole feeling of it. It’s like tobogganing on steroids. It is really niche too. It’s a random sport to get into, it’s unique and something you wouldn’t really have the opportunity to try if you didn’t live near a track. I’m always very grateful that I got that chance.

You will be competing in singles luge in Beijing next month, your first time at the Olympics. What are you feeling right now?

I am just super excited. Ever since we found out, I’ve just been itching to get on the plane down there. I’m really looking forward to the whole experience and excited for it; it’s definitely a bit surreal, for sure.

When did you find out you were going to the Olympics?

We found out probably just over two weeks ago and then it was announced publicly on Jan. 18.

How has COVID-19 affected your life as an athlete?

It definitely has a huge impact on just how we function in sport and overall definitely less travel. It’s much more stressful. We’re taking all the precautions we can to stay healthy. While we’re traveling, you go to training, come back to your hotel and that’s pretty much it. So it’s definitely much more focused on what we’re here to do, which in some ways is good, and then in other ways can be kind of exhausting.

What have been some of the best and most challenging moments or races leading up to the Olympics?

I think I found a lot of consistency over this past season and that’s something that I’m really taking as a positive. There have been so many new experiences and new places, like super cool, brand new tracks that I’ve had to learn quickly, which is a challenge, but has also been a positive.

I’d say, probably the biggest challenge is just how long the season has been. It’s a long time to be on the road and away from home, family, and friends. We’ve actually been on the road in Europe, China and Russia since Oct. 4. So, it’s almost been four months now

I thought the tracks were all just a big circle; you’re telling me that all the luge tracks are different?

Every track in the world is completely unique from any other track. So, some tracks have different styles of slotting that you need. Some could be way more technical and we call them driving tracks, and you have to be way more on the ball. Other tracks we call gliding tracks; these tracks are less technical, but you need to really relax and let the sled run to gain speed. I think the China track, the brand new one, is a mix of both of those. So, it’s pretty interesting that way. They all fall into a certain set of parameters and rules that are set out, but each track is very unique.

Do you ever feel scared hurling yourself down this track at such insane speeds?

Yeah, it’s definitely about getting past the fear. It can be really fast. You know there’s no turning back because there are no brakes or anything, so you have to fully commit to it. But I think at this point in my exciting career, I have reached a skill level that I know that I’m capable of everything that I’m going to do, and it just really forces you to trust yourself. So, I think there is always a healthy amount of fear.

What is the best piece of advice you’ve gotten from someone on your team? To do with luge or life or anything else?

Probably something my coach says sometimes is to drop the expectations, which kind of sounds bad when you say it like that. But, I find personally, I perform my best when I’m not thinking about that end result or how I want to finish, but just focusing on the progress and what you need to do to have your best performance.

What is your training like for this sport? What’s your typical day as a full time World Cup athlete?

During a World Cup week, we have five to seven training rounds before the race, but it depends on certain things, like if you’ve been to the track before and have qualified for the World Cup before. There’s usually about three days of training and then two days of break per week. And then we have gym sessions in between. To prepare for the World Cup circuit, we do a lot more volume training on different tracks around the world, where we would do four to six runs a day for two weeks straight. To really build the muscle memory and experience is so important on tracks all over the world. And then when we aren’t able to take that amount of runs, we do visualization.

You’ve already been to China in the past four months; what is it like there with their zero-COVID-19 policy?

It was very intense. It was definitely like the most intense COVID-19 procedures or policies we’ve ever had on the world circuit, which I get. When I first got there, all the Chinese staff were wearing full hazmat suits. I don’t think we saw a single person’s actual face for three weeks. But it’s good, you know, they take it seriously. We kept the whole circuit safe and healthy. It took a bit of adjusting, but you get used to it so quickly. We had PCR tests every day we were there. I wish I kept track of how many tests I’ve had this season.

Do you have another favorite winter Olympic sport you will be watching?

This is my first Olympics where I know [other athletes] personally, or I’ve met athletes that will be at the Olympics in other sports. So, I’ll definitely be looking for other local BC athletes that I see around the gym. Pretty much everything, I’m just really excited for it.

What is a piece of wisdom you can give to our readers as an Olympian?

Always do what you love, and you never know where it’s going to take you.

Natalie Corless:

Natalie Corless:

Natalie Corless is an 18-year-old luger from Whistler, BC, who has competed in both singles and doubles since 2018. Coming in second place at the Youth Olympic Games in 2020, Corless is trying her hand at singles in Beijing. The Cascade got the opportunity to talk to Corless while she was in Germany, competing in the World Cup circuit.

Corless came in 16th place on Feb. 8.

I read that you immediately fell in love with luge the first time you tried it when you were 11 years old. What exactly made the sport so appealing to you?

I think for me, it was just something so unique. I didn’t really even know what luge was before I had tried it the first time. It’s such a niche community of athletes and you get to know everyone, which makes it such a family sport in a way. You know everyone that you compete against, which, to me, is really cool.

You will be competing in singles luge in Beijing next month, your first time at the Olympics. What are you feeling right now?

Definitely a mix of excitement and a little bit of anxiousness, I think. This has been my first year on the senior World Cup circuit. It’s kind of been a lot this season, getting used to competing against all the best names in the sport. Now, at the end of the season, it’s the biggest event of someone’s career. It’s been a lot happening very quickly, but in some ways that makes it just so much more exciting.

What has the preparation been like leading up to the Olympics?

Well, probably about six months ago, I didn’t even know that this was going to be a possibility. Last year, because of COVID-19, I didn’t even travel to compete. I was just at home in Whistler the whole season training. This season, I left home in the beginning of October and I’ve been in Europe ever since. So, it’s been a super long season, which definitely has its challenges of its own. Preparation wise, I just took the season one race at a time, which was definitely a steep learning curve as my first year on the circuit. It was definitely just a step-by-step process and eventually I got the results in order to qualify, which was amazing.

What is the World Cup circuit? Is it basically the preliminary events leading up to the Olympics?

Every year, there’s a certain amount of World Cup races that happen across Europe, and there’s normally a few in North America, which unfortunately didn’t happen this year because of COVID-19. So, we traveled around to all the different tracks in Europe, and we also went to Russia this year. And through those races, you gain points depending on where you place. In an Olympic year, those points will help you qualify your spots for the Olympics.

In what other ways has COVID-19 affected the competitions this year?

We probably get tested once or twice a week, generally before every race week. Every time we travel to a new place, we’ll get tested. But, you know, there’s always tests thrown in here and there, especially before the games; we’re getting tested a lot.

You lose a little bit of the social aspects [of the games]. You don’t have spectators at the race, which makes it a little tough sometimes.

You have won many doubles races as well as singles; are you excited to race by yourself or will you be missing another person on the luge with you?

There’s definitely aspects of [doubles] that I’ll miss. Everyone starts out luge sliding singles, and that’s what I was doing for so long. [Then] when women’s doubles got introduced as a discipline, my teammate and friend and I started sliding together. And that definitely took us to a lot of really amazing places in the sport. But all in all, I’ve always really enjoyed sliding singles. It’s kinda nice to have all the control yourself.

I read that luge was one of the fastest sports in the Winter Olympics. What are you feeling when you’re sliding down the track at such great speeds?

There’s always moments in the sport where fear comes out a little bit, especially starting at a new track with new speeds and new skills, but it’s easy to turn that fear into excitement and that’s kind of something that I’ve learned throughout my time in the sport, is how to accept the fear and work with it, which is a pretty cool skill to have. It’s definitely such a unique sport and yet I can still take so much out of it that I can use in my day-to-day life.

What is your training like for this sport? What’s your typical day as a full time World Cup athlete?

It’s pretty much a full-time job. I’ve been on the road for months, but a normal training day on a World Cup circuit week would be two to three runs in a day. We really only get three minutes of sliding a day, so you gotta make the most of it. And then normally a gym session as well, because a big part of sliding is the start. The stronger you are, the faster you can start, the faster you’re going to go. Days always seem pretty full because you can be at the track for almost three hours trying to get in your three minutes of sliding.

When you train with all the other nations, the sessions can have up to 20 sleds and the sessions will span out throughout the day, and then you get to the track an hour early to warm up and get ready, and then pack up and leave after. So all in all, you know, it can be a pretty long day at the track.

What is the best piece of advice you can give to our readers as an Olympian?

My biggest thing would probably be perseverance. Just six months ago, I didn’t even know this was a possibility. I’ve gone through a lot of ups and downs in my sliding career. Lots of times I wanted to quit as things got hard. But going to the Olympics now just shows how much sticking to something, keeping your head up, and pushing forward, can lead to success. My advice is definitely to just keep pushing, because you never know what can happen.

Reid Watts found his passion for hurtling himself down hill at the age of nine when he saw a bobsleigh race. At the age of 14, Reid competed on the junior national team; in 2016 he won a bronze medal at the Youth Olympics, and represented Canada at the 2018 Pyeongchang Winter Olympics. The Cascade was able to meet with Reid just as he landed in Beijing and started training at the Yanqing Sliding Centre.

Watts came in 17th place on Feb. 6.

When you had your first slide, how did your mom react the moment she realized how fast her baby was going down a race track made of ice?

Well, of course, when you start at a young age, they don’t just send you off the top and wish you the best of luck. Especially as a nine year old. Honestly, my mom hasn’t aged into it all that well. Apparently she really struggles to come out and watch me at the track. But I think that’s a pretty common racing thing.

Where on the track do you start training and how long until you start going down from the top?

When I started in Whistler, we started near the bottom of the track at corners 13 through 16. [We only go] through about four corners – still enough surface to speed up to a slow, but comfortable, 70 kilometers an hour, and a good taste for the sport.

Then, you slowly move your way up the track as you get more familiar with everything. The process of starting at the top of tracks can take years. There’s a lot to learn – basic body position, driving points. The coaching staff has safety as their number one priority, so they’ll only send you further up and progress higher when they know you’re ready.

Does each track race and feel different, like in car racing?

A hundred per cent. Every track is completely different. They have their own characteristics and personalities. It’s exactly like car racing. The track here in Beijing is super unique, there’s really nothing like this one. It’s incredibly long and has tricky sections and corners that have interesting pressure points top to bottom, so you really have to steer the sled just right to get the optimum line for the best time. It’s a really cool challenge to go down.

Do you think the tricky nature will make the races more even?

Yeah, definitely. The uniqueness of the track, but also because of the lack of runs everyone had. The big teams, like the Latvians, the Germans, the Austrians, the Italians, we’ve all had the exact same amount of runs here, which really gives it an even playing field.

There are some tracks in Germany where the European teams had so many runs down they built the perfect sled setups for the tracks. But right now, here in Beijing, we’re all very even with each other. It really is anyone’s game. That’s what’s super exciting about the Olympics.

How did the experience of the Youth Olympics you prepare for the real Olympics?

The Youth Olympics is definitely a bit of a dress rehearsal for the Olympics. I was actually pretty surprised how similar everything was. The general vibe of village living, the way all the transportation works, the big food hall.

There’s a lot going on. We were a bunch of kids at the time. So it’s super easy to get excited and distracted. But no, the Olympics [are] a much bigger step, way more press, way more media, way more competition. It’s definitely a good step to kind of test the waters of what the show is actually all about.

How does a team relay work? What should the viewers know about the technicalities of this race?

It’s a really interesting event to watch. The way it all works is the fastest woman, man, and one doubles team lineup at each racer’s starting gate. The girl goes down the track. And just shortly after the finish line, there’s a pad where you sit up, you whack the pad. As soon as you hit the pad, the gate opens for the next racer. A reaction starts as soon as the gate opens, I go down, hit the pad, then the doubles go down and hit the pad to finish the team’s run. The fastest run wins. It’s definitely the most exciting event to watch. And that’s also the one where we have our best chance to throw down a serious time.

COVID-19 obviously has affected your training, but how has it affected the logistics end of a more niche sport?

It’s been huge, to say the least. Last year, for instance, we stayed in Whistler mostly, and we missed the first half of the World Cup races, so opted to stay back in Canada. Which wasn’t as much racing as we would’ve liked to do coming into an Olympic year.

It’s been a massive stressor. A positive [COVID-19] test here could potentially keep you out of competing in China. Before, we could really take action to control and avoid getting COVID-19. Now, you’ve got to worry about [more] with the way the Omicron variant’s been spreading. Now [that] we’re in China, in a more controlled environment, it is a big weight off [our] shoulders.

With COVID-19 and the controversies surrounding China hosting these Olympics, does that build pressure on you as athletes and representing Canada?

There’s no doubt there is controversy in the world, but I personally keep that really separate. I’m here to slide for Canada. I’m doing this for Canada. And my bigger goal is to get children who, like me, [to] always dream of going to the Olympics believing they can. We have a young team, and we’re products of the 2010 Olympic legacy. We learned how to slide in the Whistler sliding center. When I’m home I go trackside and help coach the kids who are going to be on the next generation Team Canada.

Interviews were edited for length and clarity.

Illustrations: Niusha Naderi / The Cascade

Luge photos: Mareks Galinovskis

Headshots courtesy of Luge Canada

Reid Watts

Reid Watts