By Michael Scoular (The Cascade) – Email

Print Edition: October 30, 2013

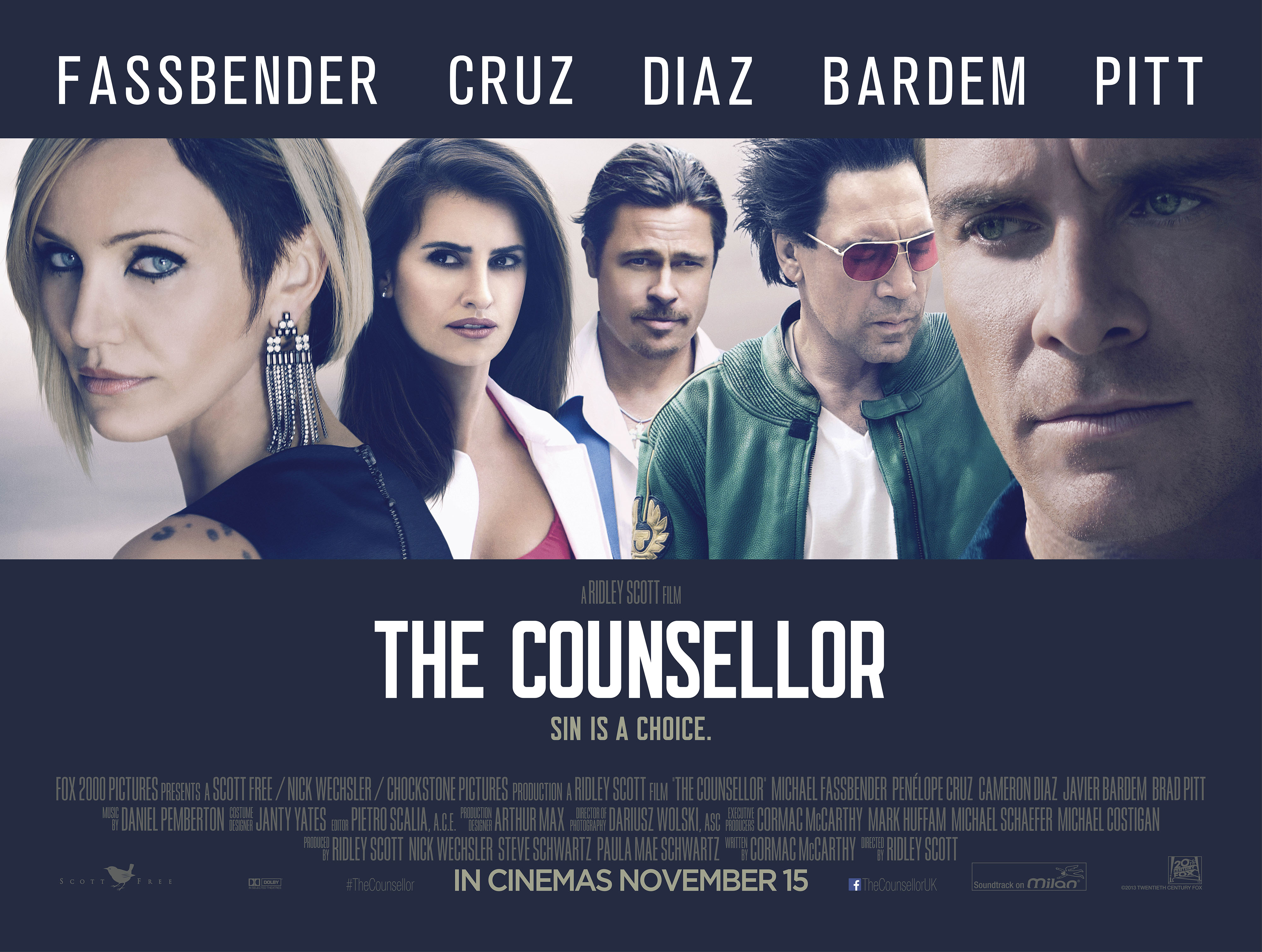

Cormac McCarthy’s prose is inimitable, but his words are increasingly making it into the mouths of people on screen. They have before in the Coen brothers’ No Country For Old Men, their plot markers were taken for John Hillcoat’s The Road, and now they have appeared, without a book to precede them, in The Counsellor, directed by Ridley Scott.

Scott, in counterpoint to his brother Tony, often directs inert movies about men moving with power. In contrast to Tony’s painterly abstraction of violence, speed, and work, Ridley has little that sets him apart visually. He is matter-of-fact. Everything he shoots has equal importance, giving his movies, most of them long since the mid-point of his career, a stateliness that carries them into upper realms of regard (Gladiator, Black Hawk Down, American Gangster). At a distance, The Counsellor looks about the same. Most of it is, visually, simply conversation, but McCarthy’s words—their sound, their difference—work in a way that makes Scott’s decorum something to be taken over, rather than informed.

Many of McCarthy’s novel-writing tendencies carry over: the setting skips between the two sides of the Mexican-American border, Michael Fassbender’s main character is referred to only as “Counsellor,” unsparing violence is either completely elided or punctuates sequences, and dialogue comes as short sentences, but never small talk. What you get with McCarthy is a unique language unsubtitled, but it makes the actors almost afterthoughts.

The plot involves drug deals but isn’t about the war on drugs. It might be about how Fassbender’s character is foolish enough to casually posit that the deal he enters into with Javier Bardem’s character might become obsolete when said war ends. It might be about how Penelope Cruz’s character believes in the magic of not knowing the exact worth of her jewellery, something Cameron Diaz’s character mocks her with until she grows bored. All of it involves a highly-valued truck that is literally filled with shit, so you can guess at some of the subtext. In case you don’t, Brad Pitt’s character at one point says, “I’ve seen it all. It’s all shit.”

McCarthy’s way with characters is strong and succinct, but one question could be how much actor psychology goes into it when it’s all in the words. Among the stars, there’s a variety of ways lines come off as coolly efficient or off-kilter in a dead kind of way that sometimes recalls last year’s Cosmopolis, based on the work of Don DeLillo, a contemporary with McCarthy. Both authors travel to the end of meaning in their works; with DeLillo, it’s technology, the consumption of art, the removal of bodies from context. McCarthy, in his writing and here, catalogues so many different ways of killing, ways human bones and flesh can be turned unrecognizable, that it amounts to not, for those left, how rare it is to be alive, but a cautionary tale against it.

While this force slices its way through The Counsellor, characters talk and talk about sex and aging and greed and the way their miniscule worlds function. Breezy, wide-windowed houses and Italian cars house most of this, scum forgiven due to their wisdom (in dialogue, though not in practice) gained solely by the virtue of growing old.

Most of The Counsellor is spoken in a language of surprise, followed by a cut that says you should not have been surprised. Words are redefined because popular usage has stripped them of their original meaning. People always ask two or three too many questions, valuing knowledge as a way of getting a step ahead, but here the hierarchy is set from the beginning, and so each question gives an answer that is totally unsavory, is totally unbeneficial to the asker, and is devastating only in terms of how far down the chain the person in question is.

This is, in short, a hopeless movie written by an author at 80 who never reserved much hope in the first place, one who sets the world up as a place where things are only ever found, not made, and everything is trending down. But it is also a reminder that, for all his high-minded allusion, McCarthy has a lot in common with other, more popular traditions, as he’s gone between western, science fiction, and crime novels. Here, he occasionally bears a resemblance to some of Elmore Leonard’s work, where prepared criminals match minds against unlikely suspects.

It’s pensive dialogue but pulp imagery, which brings the focus back to Scott, who trusts in the complications of narrative, the surprise of a set piece, despite McCarthy’s script’s insistence that there’s nothing to all this, that all action takes place on scorched earth. Either Scott has muddled things, turning this into fashionable people strutting and descending into a maelstrom, or found harmony with McCarthy, making a crumbling empire as palatable as it can get.