By Sami Al-Abduljabar (Contributor) – Email

Print Edition: June 3, 2015

We drool as teething babies, we drool when we sleep, and we drool at the sight of tasty food. But when midterms come around, drooling turns to nervously licking our lips as we produce stress hormones — which can take a toll on our immune systems.

A recent study by UFV biology student and president of the biology and chemistry student association (BCSA) Vessal Jaberi examined students’ saliva before midterms to determine whether there is a correlation between perceived stress, physiological stress, and immune system functioning. Jaberi explains his interest in this project was piqued from the partnership with his soon-to-be research supervisor Greg Schmaltz.

“We had a conversation when I went to his office hours asking him questions about a different class. At that time he was one of the science advisors at the Science Advice Centre,” Jaberi says. “The way that I came up with saliva wasn’t actually me — Greg said he wanted to use salivary cortisol.”

Jaberi says his immunology-heavy courseload at time and the intensive background research about projects to satisfy his honours biology program requirements also played a role in his decision to take on the experiment.

That decision soon proved fruitful. On April 8, Jaberi showcased his research at UFV Student Research Day and won the Vice-Provost and Vice-President Academic award. Currently, he and Schmaltz are trying to publish his research paper in a scientific journal.

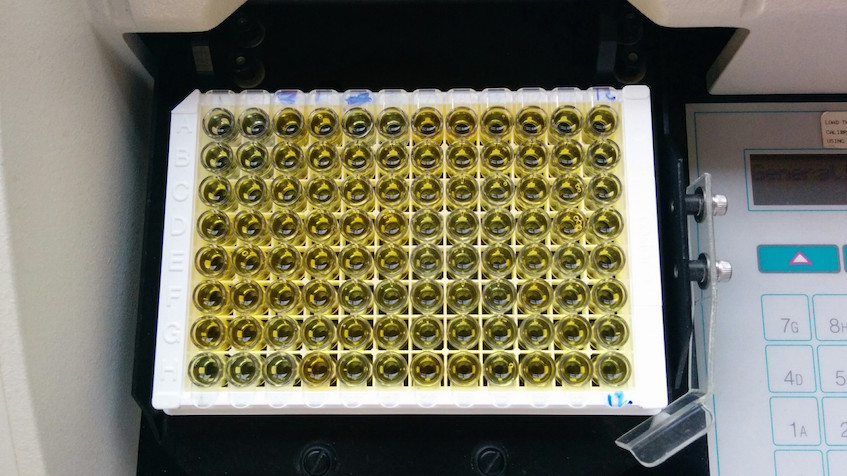

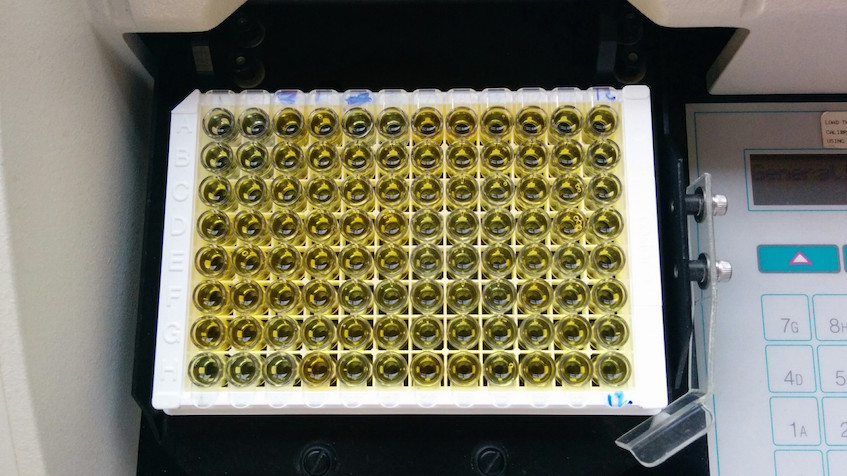

Jaberi collected saliva samples and administered a psychological survey to measure the perceived stress of each subject in a sample of UFV students. From the samples, he was able to isolate and quantify two biomolecules: the stress hormone cortisol and an immune system protein called immunoglobulin A (IgA). From this data, he was able to draw a correlation between the perceived stress from the psychological survey, the physiological stress represented by cortisol levels, and immune system functioning represented by IgA levels.

Jaberi’s results indicated a positive correlation between each of these variables — meaning that one will affect the other.

As perceived stress levels increase, cortisol and IgA levels also increase. Jaberi says the positive correlation between stress levels and IgA levels surprised him.

“I actually thought [IgA levels] would decrease just because it made sense if your stress levels are high your immune system suppresses,” he says.

He then explained that the reasoning behind this might be because he collected the saliva samples the day of the midterm, a time during which students might exhibit a fight-or-flight response that is usually characterized by a heightened immune functioning for short periods of time.

Another surprising finding from his research is that there was no significant difference in the stress levels between male and female participants or different age groups — a result that challenges other research that suggests differences between the sexes.

During his experimental procedure, Jaberi also administered a self-designed questionnaire to his subjects to determine what coping mechanisms students used to manage stressful conditions. He provided a range of positive and negative coping mechanisms including physical exercise, yoga, meditation, alcohol consumption, coffee consumption, smoking, and sleeping.

Although the use of these coping mechanisms differed from one individual to another, some general trends emerged. For example, none of the subjects in the sample used smoking to cope, but many students did not get enough sleep the night preceding the midterm. Many participants drank caffeinated beverages — which seemed to affect their body instead of their mindset.

“The caffeine obviously has metabolic changes [to] your body,” Jaberi says. “Cortisol spikes up, but because you have it so often you don’t really feel it in perception. But it was definitely effective.”

This study wasn’t as simple as handling samples and collecting data; Jaberi says he had to overcome several obstacles in order to finish his research. The first was having to go through exhaustive background research in an efficient yet timely manner. Then the experiment had to be approved by the UFV Human Research Ethics Board. Since Jaberi’s research used human subjects and deals with bodily fluids, approving the experiment was difficult and involved many experimental modifications and a lot of paperwork.

Despite this, Jaberi says the biggest obstacle was trying to come up with an affordable and feasible experiment design that would be interesting enough to attract subjects to participate in the research — while being scientific enough to yield valuable data that would allow him to write a successful scientific paper.

“I mean, I had an award for everyone who wanted to do it. Their name was put in a draw, and one person won a $100 gift card to Best Buy,” he says. “At least people had some sort of incentive.”

Although Jaberi is finished his research for now and is soon applying to the UBC pharmacy program, he says he hopes future students will expand on his project and try to investigate the effects of stress on other immune proteins.

“There is a lot that people can do with it; it is just up to their imagination,” he says.