It’s been six years since B.C. declared the opioid crisis a public health emergency. This year, as of August, 1,468 people have died of illicit drug toxicity in this province alone. So, here are the basics you need to know about a crisis that is continuing to kill our friends and family at rapid rates.

What is an “Illicit drug toxicity death”?

More commonly known as an “overdose,” health authorities have been gradually switching their language to the terms “drug poisoning” or “illicit drug toxicity” in recognition that people are dying not necessarily because they are not managing their drug use responsibly, as the term “overdose” implies, but rather the illicit drugs themselves are fatally contaminated.

“[Overdose] suggests that if they’d just been more careful, they wouldn’t have died, when we know for a fact [that] the market is so toxic right now that there is absolutely no way for people to know what’s in the substance they’re buying,” said Lisa Lapointe, chief coroner for British Columbia, in an interview with the CBC.

What is in these substances that make them so toxic?

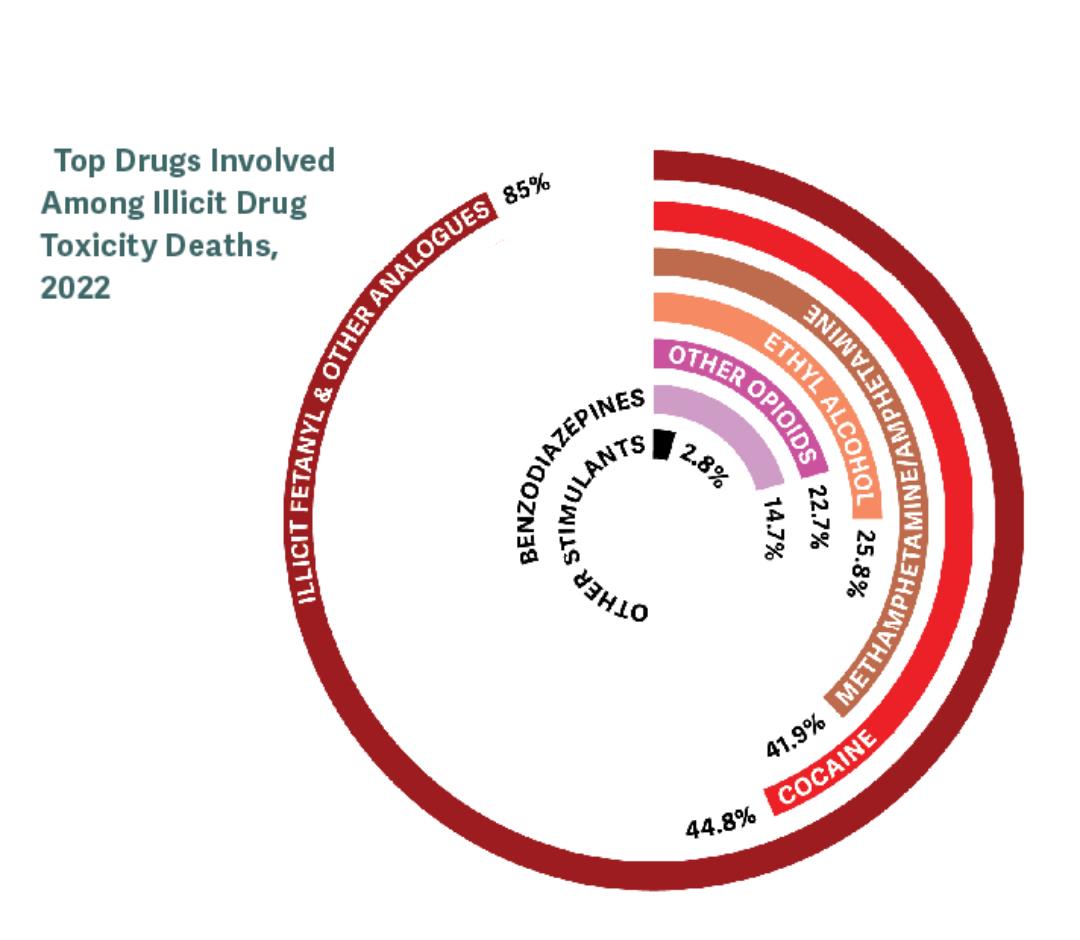

In the majority of cases, multiple substances are detected in these drug toxicity deaths, meaning that opioids (such as heroin and fentanyl) and stimulants (such as methamphetamine and cocaine) are often combined or used together. Fentanyl, a fully-synthetic opiate used to treat pain, or an analogue of fentanyl has been detected in 81 per cent of drug-related deaths in B.C. so far in 2022.

“What we used to see when fentanyl first hit our streets was very small percentages,” said Constable Mike Serr of the Abbotsford Police Department. “Like two per cent would be how much fentanyl was in a pack sold to an individual on the street. Today, it’s not uncommon to see 16 or 17 per cent … What we’re seeing now is very, very potent.”

Another commonly used substance that has reared its ugly head in the overdose spike is benzodiazepines, more commonly known as “benzos.” An anti-anxiety medication, benzos were found in 22 per cent of samples in August, 2022. Better known by some of their brand names of Xanax, Valium, and Ativan, benzos are not opioids and are therefore resistant to the opioid-blocking drug Naloxone, which makes reviving overdose victims increasingly challenging for first-responders and front-line workers.

According to Constable Serr, benzodiazepines are one of the more difficult drugs to detox from, so not only is it a challenge to revive someone from an overdose after they’ve used benzos, but it is increasingly harder to get off these drugs for people who want to recover.

“I smoked it and instantly I was fucking throwing up all over everywhere and I just couldn’t move for four days,” a 17-year-old Abbotsford resident told a Vice News reporter, recalling the first time she used benzodiazepines.

What about “safer supply”?

There has been a slow shift from pushing people who consume drugs through the revolving doors of recovery and treatment centers instead to dealing with the crisis at the source — the drugs themselves.

“This is not an addiction crisis,” says Vancouver activist and former heroin user, Garth Mullins, in a conversation with CBC News. “It’s a death crisis.”

The B.C. Coroners Service’s most recent panel stated that the primary cause of the increased death toll is due to the highly toxic nature of the street supply of illicit drugs, which is exacerbated by the province’s drug policy framework of prohibition.

As toxic drug deaths spiked throughout the province during the onslaught of COVID-19, B.C. exempted healthcare professionals to prescribe a “safer supply” of regulated substances to their patients in an attempt to save lives and get vulnerable individuals off of the toxic street supply.

The Ministry of Mental Health and Addictions reported that over 12,000 people have been prescribed safer drugs between March 2020 and December 2021. While these numbers may seem high, this program has proven to be very limiting towards who can access this safe supply, which physicians offer this service, and the strength of drugs prescribed.

This number has been refuted as being inaccurate by public health experts and advocates who claim that people being prescribed pharmaceutical alternatives to opioids, like oxycodone and hydromorphone, in order to manage withdrawal symptoms and try to wean off the street drugs shouldn’t be deemed a “safe supply.”

“The substances they’ve made available to drug users aren’t what drug users need or want,” writes harm reduction advocate Guy Felicella in an op-ed for Vancouver is Awesome. “Prescribing hydromorphone is like offering carrots instead of chips and saying, ‘Hey, you said you were hungry, and these are crunchy too!’ Most people are going to skip the carrots and find their chips somewhere else because eating chips isn’t only about hunger and a satisfying crunch. It’s also about cravings and euphoria.”

Advocates still think more needs to be done in order to disrupt the toxic drug supply, such as regulating illicit substances in the same way that the government regulates alcohol, cannabis, or food. By giving consumers the substances that they crave, along with the information they need to be able to safely consume those substances, they are able to make an informed choice that could save their lives.

“What we want is a regulated drug supply, not a safe supply,” Drug User Liberation Front (DULF) co-founder Eris Nyx told The Cascade. “The idea that drugs are safe is kind of ludicrous … Alcohol is not safe, but we do have a regulated alcohol supply right?

Didn’t B.C. decriminalize personal use of illicit substances already?

On May 31 of this year the province announced that they are going to decriminalize the possession of minor amounts (2.5 grams or less) of illicit substances between Jan. 31, 2023 to Jan. 31, 2026. This three-year exemption is in no way legalizing these substances, but rather will cause individuals who use drugs to not be penalized. B.C. is the first province in the country to receive this type of exemption from Health Canada.

While this may seem like a ground-breaking step, experts are still critical of the extremely low threshold of 2.5 cumulative grams of illicit substances, two grams less than the proposed 4.5 grams advocates had requested from Health Canada. This small threshold sets up many people for failure, as those who have mobility issues or live in rural areas often need to buy larger quantities at one time.

Lapointe also noted in an interview with CBC that racial bias and prejudice within law enforcement was a concern of hers, as police officers could interpret this threshold for personal use in different ways.

“If the thresholds are too low, it exposes [people who use drugs] to more increased police surveillance, it exposes them to having to buy smaller quantities and so accessing the illegal market is done more often,” said Donald MacPherson, director of the Canadian Drug Policy Coalition in an interview with CBC.

A letter signed by over 20 drug policy advocacy and research organizations responded to their rejected recommendations put forth by B.C.’s Core Planning Table. They argue that “a 2.5-grams threshold flies in the face of your governments’ commitment to evidence-based drug policy, anti-racism, and reconciliation with Indigenous communities.”

This isn’t the first time Health Canada has rejected proposals that could save the lives of people who use drugs. Despite support from Vancouver city council, Vancouver Coastal Health, the B.C. Centre on Substance Use, and the First Nations Health Authority, Health Canada denied an application submitted by the DULF to formalize a compassion club model of safe supply.

What are compassion clubs?

Compassion clubs are evidence-based models for distributing a safe supply of illicit substances directly to consumers, which were legally obtained from a pharmaceutical manufacturer. DULF and Vancouver Area Network of Drug Users (VANDU) submitted a proposal to Health Canada in October 2021 to legalize a compassion club model for distributing controlled drugs. Their proposal was so unique because it relied on accessing drugs through the illicit market, but ensuring these drugs were properly tested and labeled before their sale at-cost to the consumer.

Despite the rejection of their proposal by Health Canada in July, DULF and VANDU continue to distribute tested substances of cocaine, heroine, and methamphetamine in an effort to save lives. As of Aug. 31, the group has distributed 201 grams of substances with no reported overdoses or deaths.

DULF is known for distributing free doses of tested cocaine, heroine, and methamphetamine in one-off distribution events, also known as “episodic compassion clubs,” usually on major anniversaries related to the epidemic. The group handed out $3,000 worth of free drugs outside of the Vancouver Police Department on July 14, 2021.

“If people know precisely what they’re putting into their body, they won’t overdo it, no one wants to intentionally overdose,” said Nyx.

What about supervised consumption sites?

Supervised consumption sites are safe places people can go to use drugs; they are often equipped with harm reduction supplies like clean syringes and pipes and staff who can immediately respond in the event of an overdose. These sites are important facilities that help destigmatize drug use, provide a bridge of resources to people who use drugs, and save lives on a daily basis. No one has died at any supervised consumption or overdose prevention site in B.C. since the first sanctioned sites opened in 2016.

There are currently three sites in Abbotsford recognized under Fraser Health: SARA for Women, Abbotsford Mobile Overdose Prevention Site, and Phoenix Society. The first two provide services for people who consume their drugs by inhalation, a point of contention among many other sites of this nature.

These sites often cater to people who use needles, even though three quarters of people killed in 2021 due to toxic drugs had inhaled their fatal dose. Despite sites like these proving to be cost-effective ways to provide resources to those who use drugs and mitigate many drug-related deaths, they continue to get shut down around the province, especially the sites that allow inhalation.

Conservative towns like Chilliwack make it even harder for people to safely use drugs and access harm reduction services, as the city council created new zoning regulations in 2021 that required public consultation and the authorization of city council to approve overdose prevention sites on a case-by-case basis.

What is harm reduction?

As The Cascade explored in a 2020 feature on the subject, harm reduction seeks to reduce death, disease, and injury from illicit drug use for people who are unable or unwilling to stop. Harm reduction recognizes that complete abstinence from drug use may not be feasible for everyone, and therefore offers a wide range of non-judgemental support for people to be safe and healthy wherever they are at in their journey with substance use. This approach understands that there are risks when people consume psychoactive substances, so it aims to give people practical strategies to mitigate these harms.

Harm reduction is about prioritizing the immediate needs of those who use illicit substances and offering them a variety of different prevention and treatment options. Harm-reduction measures include the following: distributing safe supplies (syringes, cookers, pipes, tinfoil, etc.), giving out take-home naloxone kits, offering safe sex supplies, placing sharps disposal containers in public areas, offering Opioid Agonist Therapy (medications like methadone and Suboxone), and implementing supervised consumption and overdose prevention sites.

Harm reduction is a way to positively transform common social narratives about illicit substances and the people who use them. It is a person-centered, evidence-based approach that recognizes the multitude of social determinants that impact a person’s relationship with illicit substances. It is an approach that moves people from a privileged, morality-led position that focuses on whether or not people should be using drugs in the first place, to one of empathy and recognition that people from all demographics use drugs everyday, and these people are worthy of life-saving medical treatments.

Shouldn’t we push towards more recovery and treatment facilities instead?

In her CBC interview, Lapointe noted that people with severe drug dependencies do not make up the majority of drug toxicity deaths in B.C. The drug supply has become so increasingly toxic that anyone using any kind of illicit substances is at risk of poisoning. Karen Ward, a drug policy consultant with the City of Vancouver, said to CBC News that non-regular drug users are more at risk because their bodies don’t have the same kind of tolerance as daily users.

“Not everyone who dies is addicted,” said Ward. “[Addiction is] not what’s killing people. It’s the drug supply that’s killing people. Whether you’re using once or using 10 times a day, it’s still going to kill you.”

If anything, we should advocate for more mental health treatment and services, as Michael Egilson, chair of the Death Review Panel, recognized that people with mental health disorders or poor mental health are disproportionately represented in drug toxicity fatalities. This panel recommended first and foremost for the province to rapidly expand safe supply in all communities.

“All research shows that imprisoning people or forcing them into recovery does not benefit society,” said Nyx. “It’s incredibly expensive… it’s incredibly inefficient… unless the purpose of it is just to incarcerate people of color, which in my opinion, it’s incredibly effective at.”

“Drugs aren’t bad… in and of themselves. Drugs are a tool that can be used or misused as much as you can use a hammer to hammer a nail and you can use a hammer to smash someone in the head.”

“Some people think recovery means being abstinent from using drugs. I think recovery means recovering from a period of chaotic substance use, meaning drugs are dominating your life.”

How did the COVID-19 pandemic affect the drug toxicity crisis?

The orders from the Provincial Health Officer urged people to isolate, which was completely contradictory to harm reduction practices that tell people to never use drugs alone. The stay-at-home orders also discouraged many people from accessing life-saving harm reduction services. Services like safe consumption sites were open under limited hours and treatment centers reduced the number of beds available for people seeking help.

All of this resulted in an astronomical increase of opioid toxicity deaths — a 91 per cent increase across Canada in 2020 to 2021, compared to the two years prior. This is also due to the normal drug supply chain being disrupted due to lockdowns and border closures. One dealer from the downtown eastside blamed the Canada Emergency Response Benefit (CERB) for many deaths.

“I never made money like on the day CERB came out,” said a dealer under the pseudonym John Doe during a forensic investigation. “There were some addicts who spent their whole cheque on drugs. As soon as they got their cheque they spent it all on drugs.”

Constable Serr told The Cascade anecdotally that front-line workers became burnt out during the pandemic responding to the dual public health emergencies. “Everybody is just fatigued by the crisis,” said Serr.

VANDU member Flora Munroe told The Cascade that people who lived in modular and supportive housing were restricted from having any visitors to their rooms, which caused many people to consume alone.

“One person or a couple of people will check up on their friends or their family members to make sure they’re okay,” said Munroe. “With the no visitor policy, people have even [died] and been discovered three days later.”

Is there anything I can do to get involved?

There are several Fraser Valley-based groups you can follow and support as they work towards breaking the stigma of illicit drug use and providing life-saving support to people who use drugs.

- Moms Stop the Harm

- Mission Overdose Community Action Team

- Mission Friendship Center Society

- Pacific Community Resources Society (Chilliwack)

- Hope and Area Transition Society

- Community Action Initiative

- Abbotsford Addiction Center (part of Archway Community Services)

You can pick up a naloxone kit from almost any pharmacy. Check online at Toward the Heart’s website to see the location nearest to you. You can also pick up a kit from UFV’s Student Wellness, who has partnered with Health Sciences to offer free training on how to properly administer naloxone. Even though you may carry it around until the day it expires, naloxone is one of those things that is better to have and not need than to need it and not have it.

If you are concerned about your own substance use or the substance use of a loved one, phone the B.C. Alcohol and Drug Information and Referral Service at 1-800-663-1441.

Andrea Sadowski is working towards her BA in Global Development Studies, with a minor in anthropology and Mennonite studies. When she's not sitting in front of her computer, Andrea enjoys climbing mountains, sleeping outside, cooking delicious plant-based food, talking to animals, and dismantling the patriarchy.