by Chelsea Thornton (Staff Writer)

Email: cascade.news[at]ufv[dot]ca

On November 4th, Dr. Lionel Pandolfo appeared as the latest speaker in the Geography department’s Discovery Speaker Series. Pandolfo obtained a PhD in atmospheric dynamics and climatology at Yale University, and has worked at Columbia University and the NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies and UBC. He also recently joined UFV as an adjunct professor.

On November 4th, Dr. Lionel Pandolfo appeared as the latest speaker in the Geography department’s Discovery Speaker Series. Pandolfo obtained a PhD in atmospheric dynamics and climatology at Yale University, and has worked at Columbia University and the NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies and UBC. He also recently joined UFV as an adjunct professor.

His lecture provided an excellent opportunity, not only to learn about the research that he conducts, but also for students to experience a sample of what his upcoming course, GEOG308 Climate Change and Variability, might be like.

The lecture focused on how Global Climate Models (GCMs) can be used to analyze atmospheric variability. Pandolfo promised to “connect the theoretical with the real,” and he did this by presenting models that modelled real world events, like the effect of volcanic eruptions on atmospheric temperature, as well as models that worked within the theoretical realm, working with modes of behaviour instead of physical variables.

Dr. Pandolfo used models of the atmospheric effects of volcanic eruptions to demonstrate the power of GCMs. “I remember, the summer of 1991 – the eruption was in June of 1991 – the summer of ‘91 was really red in the sky, there was, when you looked up in the air, you might have seen that every night the sky was very red, and that is because all these volcanoes eject aerosols into the stratosphere.”

“If you look at these dates… you’ll notice that there is a dip in the temperature, because these are strong volcanic eruptions, so like I said, they eject aerosols into the stratosphere, and they also absorb solar radiation, which warms the stratosphere, which of course cools the surface.”

The volcanic eruptions’ impacts to the temperature curve are an example of how it is sometimes possible to find relationships between major physical phenomena and the atmosphere.

“To be able to do that,” Dr. Pandolfo explained, “we need to start thinking about these correlation maps [type of GCM]. Everybody can think about a pond, right? You have still water, [and] then imagine you throw a rock in it, you see at that point waves that will move away from that point, ripples. Well, if you were to do the same experiment with the atmosphere, although you definitely should not be throwing rocks in space like that, you would see something like [those ripples].”

Pandolfo presented a one-point correlation map for pressure fields in the atmosphere, which looked essentially like several sets of converging ripples on a pond. He stressed that some spots of the atmosphere might be more sensitive, where effects would cause more disturbance, or ripples, in the atmosphere.

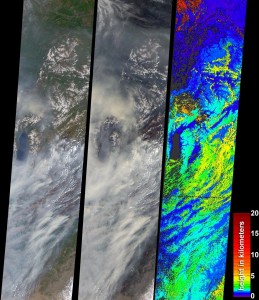

Pandolfo described another form of model: the planet model. The image he showed was of a slice of earth with the atmosphere above it. The atmosphere is divided into cubes, with each cube representing a piece of the atmosphere. Each individual cube is modelled independently, and then, in the planet model, the pieces are allowed to interact with each other. When the planet model is run, it calculates the impact of the transfer between the boxes in order to predict the temperature under the complex condition represented by the myriad of boxes. “Of course, because the model is theoretical, you are able to run the model for many years.”

Although Pandolfo’s intention was never initially to investigate global warming, the models with which he works are useful for testing predictions about the causes of warming, and for projecting future temperatures. By layering models of the atmosphere at different levels alongside models of greenhouse gases, pollution and large physical events, it is possible to build up a more complete view of the driving factors behind global warming, and their interactions with each other.

“The data, the answers, could all be there [in the models], if you know how to look,” Dr. Pandolfo concluded.