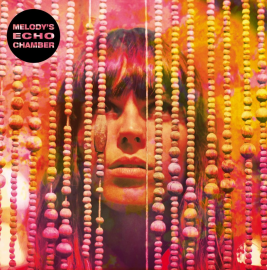

Melody’s Echo Chamber

Melody’s Echo Chamber

Melody’s Echo Chamber is a place where musical motifs circulate freely and discombobulating phasers create a heady rush of unfamiliarity. Take album opener “I Follow You,” an echoing twelve-string arpeggio is sliced open by a drum riff that unexpectedly re-frames the rhythm of the entire song. Throughout the album, Parisian songstress Melody Prachet’s clear, classically-trained vocals are rendered in a dreamlike cocoon of reverb. In a debut record produced by Tame Impala’s Kevin Parker, Prachet considers isolation and what it reveals about the self through a cavalcade of colourful melodicism and ever-changing sonic terrain. This is brought to life by Parker’s distinctive juxtaposition of frothy, swirling psychedelic shades and sharp, incessant drumming. There are nods to Prachet’s psychedelic forebears, yet the record’s trips are designed with payoff in mind. The brief instrumental “Is That What You Said” cleanses the palette with a choppy, electronically distorted rave-up before Melody dives into the sweetly-sung, “Snowcapped Andes Crash.” A simple four note melody anchors the song which seamlessly switches from the French verse to English refrain. When Prachet dispassionately sings lines like “Me and my lover / are go-ing to die,” they take on a nursery-rhyme menace that is all the more terrifying for her delivery.

Carly Rae Jepsen

Kiss

If Carly Rae Jepsen was ever just a singer-songwriter, that side of her has since been absorbed into the megamonomaniacal hardware of this radio pop star’s image. So much of the discussion surrounding Jepsen amounts to only distraction away from what the whole ascendancy of “Call Me Maybe” as the new Canadian anthem was based on: Jepsen’s contribution as lyricist-vocalist. As an example of current/future pop, Kiss is light on breaks from overpowering and incessant arrangements of flaring beats while autotune has its way, as on “Hurt So Good.” But then there’s the captive, earnest dramas of “More Than a Memory” and “Your Heart Is a Muscle,” the way “Tonight I’m Getting Over You” enters into the “We Are Never Ever Getting Back Together” conversation with even fewer qualms and uncontainable force of emotion. Kisscontinues to make the case for Jepsen as a megaphone emoter with a mind to multivarious possibilities, struggling to find one that satisfies. On “Turn Me Up,” Jepsen equivocates herself with the technological representation of herself before destroying that notion with “I don’t think it reaches;” and on “Wrong Feels So Right,” the opposing gaze is turned back on itself with a sarcastic “now what could you be looking at me for?”

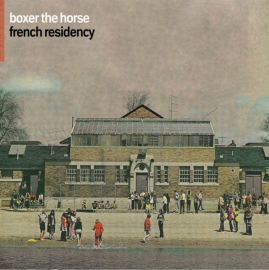

Boxer the Horse

French Residency

Winners of the Bucky Award for Best New Band of 2010 by CBC Radio 3, Boxer the Horse meld the easy-to-love slacker-rock sound and styles from the Clinton administration. Their sophomore release French Residency—recorded in their hometown of Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island—is undoubtedly frontloaded. The opening three tracks “Community Affair,” “Sentimental-Oriental” and “Rattle Your Cage” all invoke the coherent sound and laidback sarcasm of Brighten the Corners era Pavement tunes. There are a few tracks that only half work for me, like the uninspired, Vampire Weekend-esqe “Party Saturday” and the bizarre “Karen Silkwood” that weigh down the album’s initial flourishes. French Residency is sophisticated, but wise-assed; melodic but multifaceted; and their love of loud/quiet ‘90s guitar rock is untainted and it translates into the songs and the sound, showing great deal of promise. It’s hard to point a finger at a band like Boxer the Horse, because their intentions are obviously good, but in the end the record fails to add up to a satisfying whole, as the shiny alt. rock appeal begins to wear thin during French Residency’s second half.

C.R. Avery

Act One

Act One is for those albums interested in imagery and wordplay, and though the musical arrangements on the album are on the surface just songs, the instruments are background to C.R. Avery’s beat-like poetry of two prime foci: women and the travails of city life. Introducing the musical or dramatic arc that the album’s name promises the work to be part of, “The Gospel According To The Purple Cotton Dress” works as overture, explicating the themes of the whole work: “sundown in a small village called East Van” is the setting; women and junkies are the characters. Avery characteristically exemplifies his pensive, poetic sensibility when he asks, “How come the worst drug known to man has the same name as a woman with fierce inner light?” in “A Kind Man of Alexander.” He whispers this to sound like “fears in her life,” adding a layer of complexity to the subject. This is the good. But can the words make up for the lack of music? The songs are close to early Tom Waits in sound and voice, but they are ballads without energy or rhythm. Truthfully, this album was a book of decent poetry spoiled by a symphony orchestra.