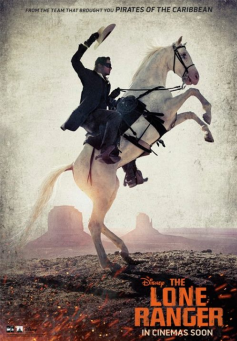

Print Edition: July 17, 2013

As a messy 150-minute history epic (or so it aims to be) must begin, The Lone Ranger opens not with its own story, but its future’s. Gazing on its own nostalgia with a measure of contempt, the tag team of the white rider (Armie Hammer) and native tracker (Johnny Depp) is not simply brought back for chases and triumph (though that is part of the formula), but summoned into the present to contain its own desire for easy narrative and solution while tracking in the guilt of the original imperialist attitudes that made the original series’ pairing seem novel.

As a messy 150-minute history epic (or so it aims to be) must begin, The Lone Ranger opens not with its own story, but its future’s. Gazing on its own nostalgia with a measure of contempt, the tag team of the white rider (Armie Hammer) and native tracker (Johnny Depp) is not simply brought back for chases and triumph (though that is part of the formula), but summoned into the present to contain its own desire for easy narrative and solution while tracking in the guilt of the original imperialist attitudes that made the original series’ pairing seem novel.

So many blockbusters this year have made it their smart pandering or misguided serious responsibility to invoke, include and project the current landscape of political distrust and contemporary disillusionment, taking idealists down several pegs when they’re not making not-so-subtle references to recent national crises. There’s the theory of cinema as coping mechanism, or as a platform for engaging comment, but in commercial moviemaking, that’s rarely what’s remembered. The scattershot way it is often undeveloped (an image of disaster relief, or a non sequitur remark to tragedy, and nothing more) makes it dubious how much of it is a filmmaker’s idea and how much just happened to be around, touched by a wide-as-possible appeal-begging script and pitch.

The Lone Ranger carries some of this baggage, but in an unexpected way. Gore Verbinski’s film’s closest recent relative is Django Unchained. Like Tarantino’s, it’s a weird mix of apologia and action-comedy, both exploitive and self-exploding, not as genuinely angry in result as it might have been were it committed to what it frequently alludes to, but surprisingly uncommitted to making an audience feel comfortable about its history.

Like Verbinski’s The Mexican, which made a movie-long joke of Brad Pitt’s character’s American self-centric ignorance of any language or life not his own, The Lone Ranger is a movie where many exterior collaborators seem unprepared for or unaware of the film’s best moments. Hans Zimmer, who now only writes scores for Nolan-level nuance, only emphasizes the back-and-forth movements of the script. A rewrite job by Justin Haythe, it unambiguously paints capitalistic progress as the villain of the piece and reminds the present of injustice, yet also stretches to lighten the mood with unrelated recurring jokes, as if, squeamishly, there is a limit to just how much reckoning with reality a popular movie is allowed to do.

Not that there’s any actual change to be found in the after-effects of even the most didactic (and, from its frame story, The Lone Ranger is a bit of that) story – however “blistering” or “accusatory” Django Unchained may have been, most of that was absorbed or discarded by the overall culture of coolness, the result a series of lines and an image of summation. With The Lone Ranger, there’s the inscrutable figure at the periphery of each part: Depp as an outcast, memory-repressed Comanche. Like a lot of The Lone Ranger, the idea originates from a movie. Verbinski references Leone, Zinnemann, Ford and more, with varying degrees of revisionism, some losing the source picture’s vitality in translation, as in the case of Jim Jarmusch’s Dead Man, known for its rare consideration of Native American life in American film, but here the basis for Depp’s mixture of silent film stoneface and humorous mannerisms. None of these problems (including the one of building a history out of films already one or more steps removed from any real account) go away, but The Lone Ranger’s at times perplexing inconsistencies by their nature beg question by diverging from the near-nostalgic, permanent past-ness that has come to mark most modern instances of being a finely crafted western.

For The Lone Ranger’s first half, it is actually a very compact movie, involving the law rallying after a wanted man like more than many westerns. What Verbinski does do well is discern the energy of movement and the necessary—and no more—place of dialogue, making great action scenes that complement the tone of violence beforehand. There isn’t a contemplation of its effects as in Dead Man, but a considerate half-step towards it, reveling more in the pairing of two of cinema’s enduring expressions—galloping horses and charging trains—than any use of guns.

Balancing regret and its never-ending futility next to laughter, Verbinski doesn’t make a movie that truly links with his references or to future installments. It isn’t a movie more sophisticated or advanced in its way of thinking than any of them: genre, images or racial borderlines. It is unchangeably part of the current way of making blockbusters. It also, in tracking its own demise, is unlike and superior to any of the others it is already being unfavourably compared to.