Print Edition: March 5, 2014

Words do not come easily when sorrow is involved. Most of the great moments in Hayao Miyazaki’s films are silent: the aftermath of human destruction, the passage of an injury, a razor’s edge escape, a leap and flurry of colour. Take up any Miyazaki film, even the weaker ones, and you’ll get a full spectrum of devastation and idealism, a critique of human neglect, a specific vision of life, more precious because he’s one of the few filmmakers who has never shied away from talking to children about the death and loneliness the world is capable of. To find the words, Miyazaki uses genre, fantasy, and what can be called imagination in the truly surreal sense of the word.

In The Wind Rises, Miyazaki opens with a quote from the French symbolist poet Paul Valéry that becomes a code, a mantra, a goal unmet, and a signal that Miyazaki is doing something strange and different with what might be his final film: making a movie out of the unfixable tragedies and political amnesias of recent history, without the overlay of alternate worlds or myths. It’s early 20th century Japan, and the inspirations that seize upon characters are artists in Europe, technological advancement, and the accelerating exchange of ideas between nations.

The Wind Rises is a movie about Japanese aircraft development before and during WWII that’s haunted by the knowledge of what everything its characters are doing will mean. But then, The Wind Rises is also a movie about the designer of Japanese aircraft (based on the real-life figure of Jiro Horikoshi), who hears from his mother early on that “violence is never justified” and dreams of beautiful passenger craft with no room for guns. Scenes of Jiro and his team of engineers closely resemble the collaborative atmosphere of an animation studio, and it’s hard not to see how Miyazaki is throwing all of his ideas about art and its responsibility to the world together, mostly leaving them unresolved.

Despite how films and people are always divided between pro- and anti- war, The Wind Rises resists the utility of being one or the other. There is no scene that visually accounts for the death his creation caused, outside a few flames and clouds of smoke, no personal downward spiral. For a Studio Ghibli film, it’s strange to see a artist’s epic about a man devoted to machinery. The only time green really appears is as a takeoff strip. The studio’s animation gives life to firing pistons, personified cylinders, steel and rivets. Wood is made obsolete halfway through. And Jiro is unconflicted in this area of his work, calling everything beautiful or wonderful. He looks, in awe, at German airship designs. “You think we are sharing this dream?” says an Italian designer Jiro idolizes — like a challenge — in one of his dreams, and Jiro believes so.

But Miyazaki does not let this side of the story advance uncontested. Though Jiro’s imagination (with dreams of Europe — mandolin and accordion — providing the main themes of Joe Hisaishi’s score) is the grand gesture Miyazaki details, there’s the clear sense idealism is not enough. Jiro is dead to the world, he’s apolitical, likely to be offended only if someone proposed stunting or sabotaging his work for the sake of life, not art. Some of the controversy in both Japan and the U.S. about The Wind Rises is how it reads as a nation continuing to willfully forget its wrongs. In those cases, Jiro is being read as a stand-in for an entire country.

But Miyazaki is more interested in an individual, not an allegory. Jiro does fight at first, to get his creative voice funded, to see his calculations and sketches put into physical models, and his managing and military overseers allow him these small victories, so long as he continues to be useful to them. It’s a picture of industrialized creativity, a much more grim and unthinking version of the preparation of violence than the more entertaining, more obviously anti-war parts of Howl’s Moving Castle. Still, Jiro is the one who gets the loudest say. Discussion of the situation outside their priviledged engineering posts becomes the pretext for a Schubert-melancholy stroll. Taking his situation in, Jiro can only say to a friend “We’re not arms merchants; we just want to build good aircraft.” Jiro’s character might have worries, but never the weight of awareness of having a physical body.

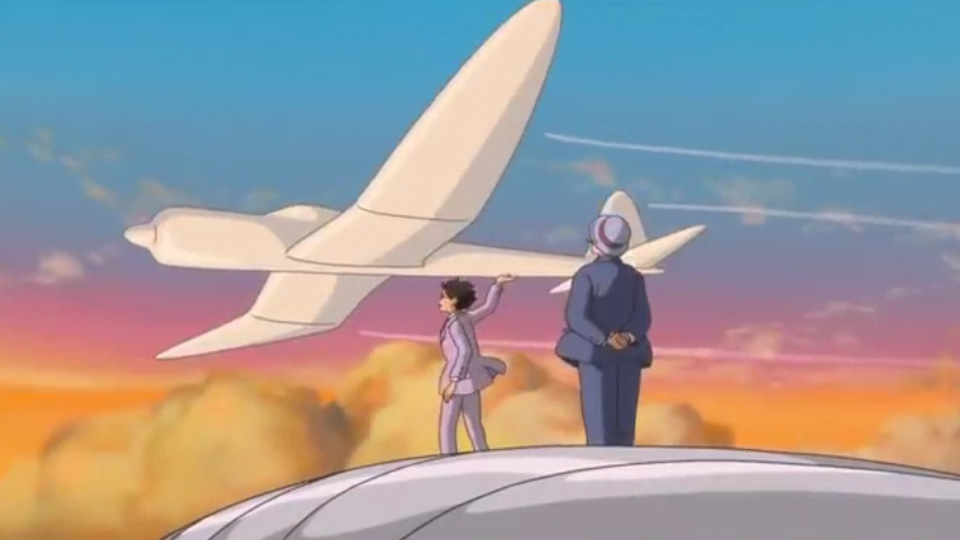

Miyazaki did not arrive making masterpieces. Working out the mix of action and environmentalism he would become known for, he made Nausicaa, before that, TV work. The Wind Rises is something different, another, arguably unfinished, arrival: an attempt to grapple with history by using the most conventional forms there is: the biopic. Chronologically following Jiro’s development, Miyazaki also diverges from one of his attributes as a storyteller. Out of place in the world of children’s animation and filmmaking as a whole, most of his stories show people, female and male, that are capable of love, but where in most movies that word is synonymous with marriage, Miyazaki’s characters are able to form a bond of respect and support, a mature form of friendship, even if they are often children or young adults. In The Wind Rises though, the only break from Jiro’s work is a countryside vacation hotel stay, where he meets a well-cared-for painter. Their courtship, of rhyming gestures, paper airplanes, and a sense of inevitability, is retrograde, dutiful, and lacks the feeling of emotional truth Miyazaki usually works into even his films’ most maligned characters. As the only break from aircraft in the film (and Jiro speeds back to his job the first chance he gets), it’s either a flimsy excuse for romantic imagery (Jiro, again, comments only on how beautiful what he sees is), or a barely considered live-to-work or work-to-live argument.

There’s no shortage of grace notes or fantastic aural sweep in The Wind Rises. It captures a keen sense of the dissatisfaction and energy of creative work. But in aiming at the most significant rupture in history’s last hundred years, Miyazaki’s possible final work is filled with confusion, mistake, and loss, with only a poem to light the way. Where many of his other films end by ecstatically opening a way forward, this one looks back with tarnished pride, regret, and restraint.