We’ve all been in some kind of difficulty where we were in need of assistance. I’m sure some of us have even thought our current world is in need of saving. Over the generations, there’s been one consistent saviour — the superhero.

Superheroes transcend generational boundaries and often reflect the values and current trends of the societies and cultures creating them. Often, the superhero(es) will fight against anything threatening these values, and in some modern examples, will even fight against values held by society. Why are superheroes so influential in our world?

The history of superheroes

Historically, superheroes were based on the antecedents of religious, mythological, or folkloric significance. For example, Hanuman, the Hindu god and divine monkey, had special powers bestowed upon him. Perseus was a Greek hero and slayer of the monster Medusa. Robin Hood and his distinctive archer’s clothing robbed from the rich to give to the poor.

Before the term was coined, hero characters were created mainly through fictional writing, until the term superhero was coined in 1899 and the superhero trope was widely spread. Masked vigilantes roaming the Wild West, enforcing some version of the law, were written about in story books and are considered the predecessor to the superhero. Even today, vigilantism is considered a form of American tradition and is frequently in the news.

Before the term was coined, hero characters were created mainly through fictional writing, until the term superhero was coined in 1899 and the superhero trope was widely spread. Masked vigilantes roaming the Wild West, enforcing some version of the law, were written about in story books and are considered the predecessor to the superhero. Even today, vigilantism is considered a form of American tradition and is frequently in the news.

“Many times the vigilantes were seen as heroes and supported by the law-abiding citizens … Where the ‘law’ was deemed weak, intimidated by criminal elements, corrupt, or insufficient,” blogger Kathy Weiser writes.

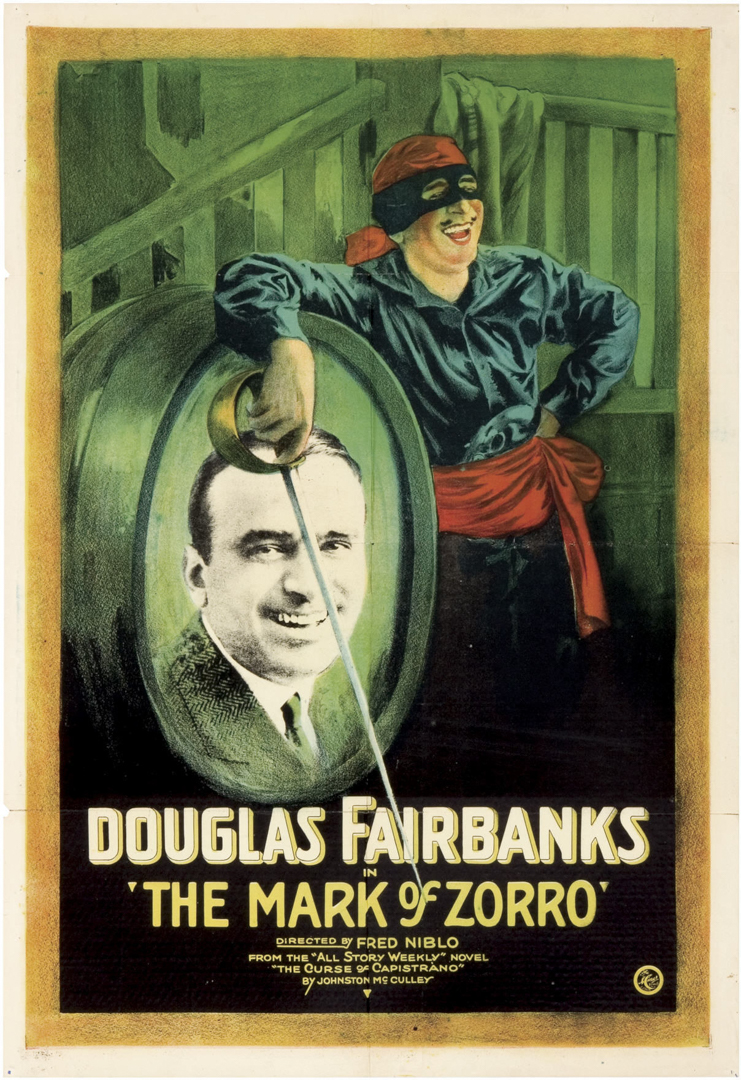

The evolution of the superhero continued through the early decades of the twentieth century as writers fictionalized their characters in books, magazines, and sensationalized yellow journalism — journalism that exaggerates a person’s actions to make a more appealing news story. Writer Johnston McCulley created Zorro in 1919 as one of the first masked and costumed superheroes. As public appeal in heroes grew, many other writers created characters with masked identities and costumes to represent their special talents or superpowers.

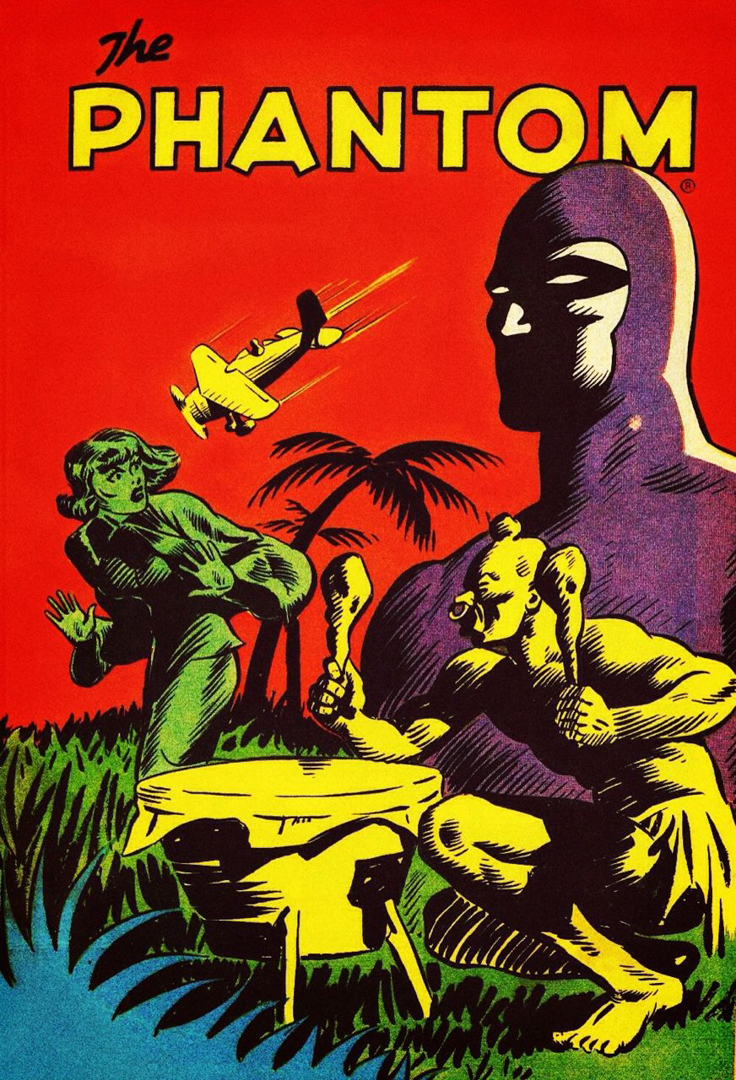

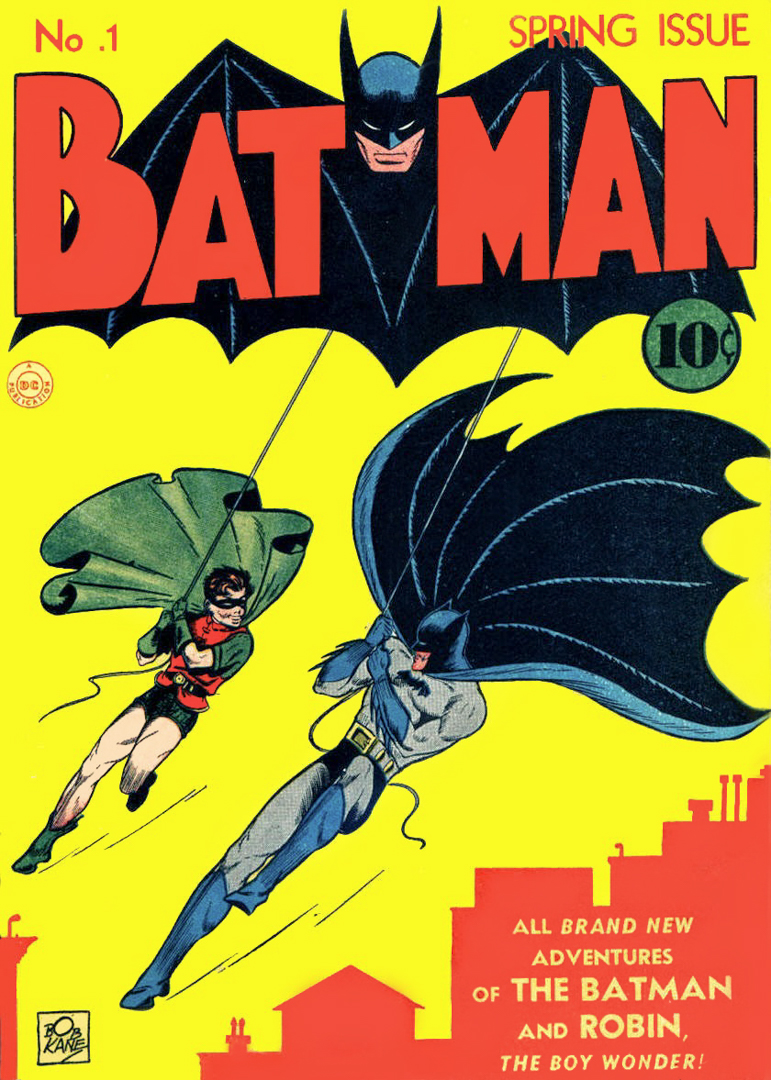

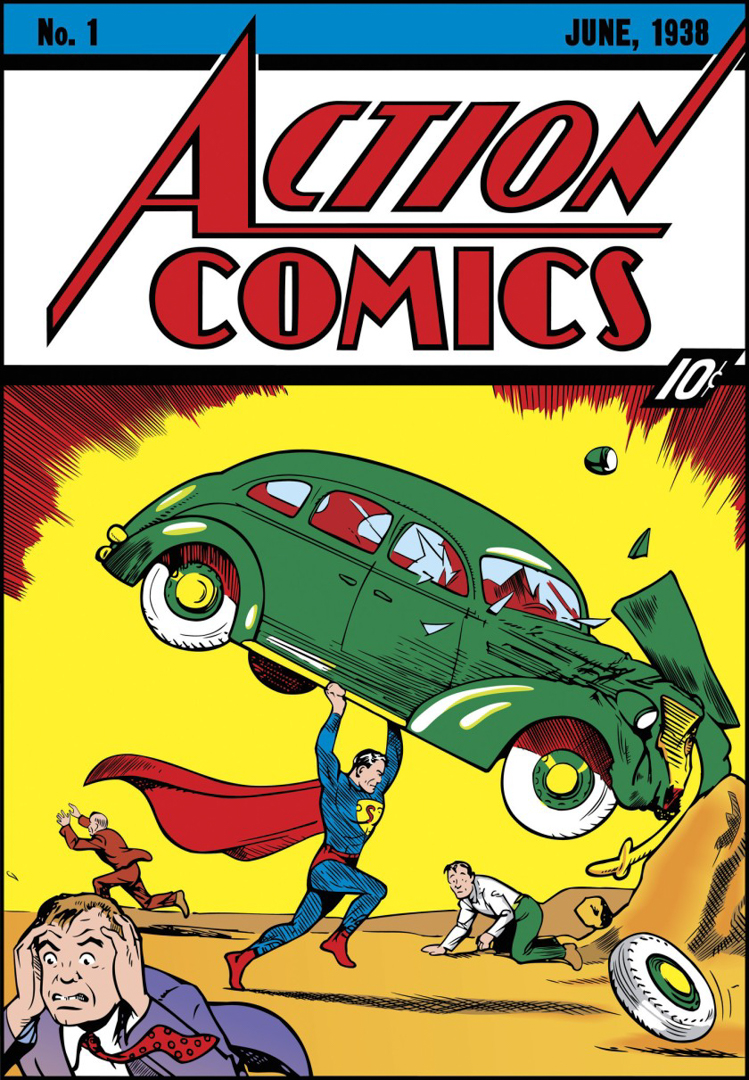

The first superhero comic, featuring The Phantom, was a newspaper strip appearing in 1936. American writer Lee Falk created what was to become a template of sorts for future costume-clad superheroes in comics, and, in a greater sense, the superhero universe. Today, the superhero universe and all the characters within continue to loosely follow the stereotypes Falk and McCulley introduced. Clear examples include Superman, Batman, and the original Captain Marvel — all white, male heroes in tights with masks or hidden identities.

The first superhero comic, featuring The Phantom, was a newspaper strip appearing in 1936. American writer Lee Falk created what was to become a template of sorts for future costume-clad superheroes in comics, and, in a greater sense, the superhero universe. Today, the superhero universe and all the characters within continue to loosely follow the stereotypes Falk and McCulley introduced. Clear examples include Superman, Batman, and the original Captain Marvel — all white, male heroes in tights with masks or hidden identities.

UFV instructor Brett Pardy dedicated his master’s degree to studying Marvel’s superheroes. Pardy is the instructor of a Communications special topics course, MACS 299H, Superheroes: Mass Media and Representation. The course covers two major concerns through the lens of superhero culture:

First, the modern mass media industry and its focus on mass media franchises.

“The same characters are available on different multimedia platforms,” Pardy explains, “and their merchandise is more important to companies, which far outsells superhero comics over the past 40 years.”

Second, the critical theories of representation around race, gender, sexuality, and disability. A deeper course study includes “how superhero hero stories have been used to generate empathy and inclusion for marginalized groups,” Pardy says.

In the post-WWII era, superhero audiences consisted mainly of children, and offered lessons about social interactions and simple social structures like right and wrong or being prosocial. In the 1980s, laws changed, allowing popular culture to market directly to children, and subsequently to sell the superhero universe as part of the TV and film industry. This deregulation allowed for companies to influence audiences to reflect on whatever they desired.

“Superheroes began as a form of entertainment for all ages in the late 1930s and early 1940s,” Pardy explains,”but because of a moral panic in the 1950s, they became a form of entertainment primarily aimed at children [with tight regulations]. Comics throughout the 1970s and 1980s worked to get back to something that was aimed at teenage and adult audiences.”

However, any belief that children were gaining positive reinforcement and life lessons was challenged by a study published in the Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology on the effects of superhero culture on kids. Brigham Young University family life professor Sarah Coyne found that exposure to the superhero culture led children to exhibit aggressive behaviours and elicit a reduction in cognitive and emotional responses when exposed to violent content and media.

Saving the world from evil while doing heroic deeds is a tempting story to play out for children and adults alike. Kids today have moved away from reenacting versions of action hero battles and have grown into watching superhero feature films with realistic battles scenes. While there is something special about first experiences seeing well-made superhero movies, the impact of such realistic violence must be researched.

The emotional reaction after Marvel’s Endgame is an example of the impact superhero culture can have on people. In the post-Endgame superhero world, with so many superheroes eliminated in a single moment, fans were left grieving the loss of their favourite characters. The years after were spent debating what would come next for the Marvel universe.

“I enjoy the imaginativeness of their [superhero] worlds,” Pardy says, “especially in comics where the story never really ends. The story has to be more imaginative to explain why it keeps going. It also means the story has to keep reacting to changing social trends and current events.”

The superhero universe has thousands of costume-clad characters, with Superman, Batman and Wolverine listed as the most popular. The Marvel universe is more popular than the DC Comics’ universe, but the two combined dominate the world’s superhero markets much like Amazon or Facebook dominate their respective industries.

The superhero universe has thousands of costume-clad characters, with Superman, Batman and Wolverine listed as the most popular. The Marvel universe is more popular than the DC Comics’ universe, but the two combined dominate the world’s superhero markets much like Amazon or Facebook dominate their respective industries.

With such diversity, any theme, social issue, or world event can be addressed in any way the writer or creators desire.

“The great part about superheroes is they are not really tied to one genre,” Pardy says, “instead they have the ability to be any genre, or all genres, and can borrow from horror, mystery, science fiction, et cetera.”

Superheroes are not always doing good deeds

Superheroes are often immortalized for their heroic deeds, upholding justice, saving the planet, or defeating an arch-villain, but what about superheroes who failed miserably or were thrown into the superhero scrapyard?

The troubled superhero, often called an anti-hero, has gained popularity in recent years and can often be far more relatable than the untouchable superhero of the past. Dr. Eric Bender described in Psychology Today how people can relate to the moral complexity of anti-heroes.

“They’re flawed. They’re still developing, learning, growing. And sometimes, in the end, they trend toward heroism. We root for their redemption and wring our hands when they pay for their mistakes. They surprise us. They disappoint us. And they’re anything but predictable.”

We can see anti-heroes in characters such as: Punisher (1963) is a military veteran turned vigilante in his campaign against criminals and organized crime. John Hancock (2008) is a drunken, anti-social superhero who is over 3000 years old. He often causes more damage and destruction than is necessary. Deadpool (1991) is a disgruntled mercenary with powers of regenerations and dark humour.

Some of the arguably worst superhero characters include: Dogwelder (1997) is a superhero welding dead dogs to the faces of his enemies that didn’t catch on for obvious reasons. Squirrel Girl (1990) has superhuman abilities resembling a squirrel’s, yet she unbelievably defeated Thanos in an off-strip battle. Arm Fall Off Boy (1989) can detach his limbs to beat villains.

Government use of superheroes for propaganda

“There’s a belief that superheroes are kind of fascist,” Pardy says, “the idea of strong individuals imposing their will, but really it’s what academic Matthew J. Costello calls liberalism with a fascist aesthetic.”

Governments certainly do use the superhero trope for propaganda. Starting in the second World War, the U.S. Government started using various forms of media to influence the way their population thought about the war. Posters, news reels, and movies were popular media used to target and inform adult audiences while comic books and superhero propaganda aimed at young audiences with the creation of heroes like Superman (1938), Batman (1939), and Captain America (1941). The use of superheroes as a means of propaganda continues, with more recent examples including attempts to reimagine 9/11 and the War on Terror.

Governments certainly do use the superhero trope for propaganda. Starting in the second World War, the U.S. Government started using various forms of media to influence the way their population thought about the war. Posters, news reels, and movies were popular media used to target and inform adult audiences while comic books and superhero propaganda aimed at young audiences with the creation of heroes like Superman (1938), Batman (1939), and Captain America (1941). The use of superheroes as a means of propaganda continues, with more recent examples including attempts to reimagine 9/11 and the War on Terror.

Governments need their populations to respect law and order to function effectively. Using superheroes to help reinforce government doctrine is a questionable practice because it often divides audiences and forces people to choose sides. The “with us or against us” mentality, prevalent during the Bush presidency, was at the forefront in the recent superhero civil wars.

It’s well known that superheroes often abuse their position of power to achieve their own purpose, or the purpose of those giving the orders and directives — the alcoholic Hancock’s brazen destruction of cities, Deadpool’s comic madness. In doing so, the superhero’s behaviour is often called into question. Writers and creators can then use the intent behind the superheroes actions to make a point, political message, or address a societal concern.

“The deniability of allegory becomes a forum to ask questions about the ethics of power,” Pardy says. “Violence is a constant, but who orders the violence, how lethal the violence is, and if the motive for the violence is to further the ends of the powerful or to aid the less powerful can alter the meaning.”

Superheroes, or their variants, will continue to frequent history in all manner of spoken and written word, art, music, and multimedia. Superhero movies represent some of the largest grossing movies of all time and there’s no expectation for that to end. Comic books and strips have been a major fixture in the superhero universe for more than a 100 years and continue to provide millions of readers with regular content. The multi-billion dollar toy action figure industry also contributes greatly to the impact superhero characters have on our lives.

Superheroes are seen in action everywhere from portable technology to the big screen. They are read about. They are played with. They are worn. There’s no doubt that we have made them part of our everyday lives. Regardless of our personal taste, superheroes are here to stay.

“I think that Spider-Man’s motto, ‘With great power comes great responsibility,’ are great words to live by,” Pardy explains, “and superheroes are inspiring to me because in a world where so many people use their abilities for selfish reasons, superheroes use theirs to help others.”

Images: Marvel Comics/DC Comics

Steve is a third-year BFA creative writing/visual arts student who’s been a contributing writer, staff writer and now an editor at The Cascade. He's always found stories and adventures but now has the joy of capturing and reporting them.