Then it hit me.

I frantically tacked six white sheets of paper up on my living room wall and started planning — I would make my very own zine. It wasn’t such a far-fetched idea, was it? I had a small group of art-savvy friends, a few who wrote and edited, and I had a bit of zine experience under my belt from my time working on The Cascade’s ‘The Zine.’

The thing about being unemployed is that you have a lot of time on your hands to do useless things like read books on Frank Zappa. Zappa, an artist and musician popular in the 1960s, was an outspoken, self-proclaimed “freak” and an overall menace. To be honest, I didn’t really care enough to finish the book. I did, however, like his name. It was catchy — Zap! The sound was electric, sharp, and sudden. I wanted our zine to shock people, to grab their attention, and to inspire them to care about their community. It was decided: our zine’s name would be Zapta.

But hold up — what in the world is a zine?

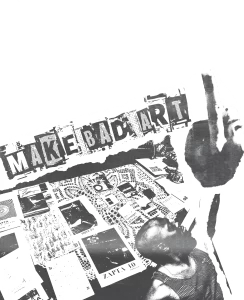

A zine (pronounced zeen) to put it bluntly, is a crappy, cheaply-made magazine or booklet. Zines have long been self-published vehicles of expression for socio-cultural groups who’ve been neglected, silenced, or dismissed by the mainstream. They don’t try to imitate high quality publications or art; rather, they embrace imperfection and reject professionalism, letting the art, writing, and ideas breathe. Zines aren’t meant to be shiny, flashy, expensive, or heck, even well written and designed. They are a collaboration of passionate people doing things that they’re, well, passionate about, regardless of skill.

Zines have been around since the early 20th century, popularized by science fiction fan clubs in the 1930s and 40s. They became a component of the punk movement in the 70s and 80s, the Riot Grrrl underground punk feminist and Queercore movements of the 90s, and provided publication alternatives for comic-makers in the 80s and 90s.

According to Aimée Henny Brown, a transdisciplinary artist, zine-maker, and assistant professor in UFV’s School of Creative Arts (SOCA), zines are a great alternative for self-publishers.

“Zines came about to give voice to topics that were not being accepted or appreciated by larger publication houses or more formal publication institutions … like alternative fictions, queer fictions, counterculture movements, punk movements, anything that’s politically outside of the big arena of political discussion. Zines are a way of sharing some of that information that’s underground and allowing people to find cultural resonance, to find community.”

Let’s back up to that winter’s night. On the cusp of midnight, I texted my friend: “We’re starting a community development zine,” I said, “and you’re going to be one of my editors.” Being a person who enjoys sleeping at night, they replied with full support in the morning; a resounding “go for it!” A few more texts here and there, and I had a group of people on board to help me manifest this crazy, semi-drunken dream I had tacked up on my wall. Within weeks, I had an editor, a designer, two writers, an illustrator, and a photographer, and we all gathered in my little apartment for the first time. What happened after that shocked me and changed everything in my life.

But first, a little history. When I sat down with Henny Brown to talk about her zine-making practices, I was surprised to learn that she and I had both gotten our start making books with our mothers as children.

“The first zine that I ever made, I made with my mom. I would draw pictures and then we would put wrapping paper on it as a cover and then my mom would write in text if I was telling a story … So book binding, book medium, multiples [a piece of art with duplicates] have always been part of how I look at the world or make sense of things, and it’s certainly an activity that I’ve had throughout my whole life from very early childhood.”

For those of us who know, know. The magic of art and community is that we find stories like this. There is beauty in these communal connections and lineages, and being able to trace that history together alongside a reassurance that this is something we are destined to be doing.

“It’s kind of amazing, I think, to connect that timeline of things,” Henny Brown said.

Now, back to Zapta’s most groundbreaking moment. It was Jan. 3, 2023; everything was in place. Our designer had put the finishing touches on our booklet and this little, digital zine was ready for the world, baby. I uploaded the PDF file to a host site and our first issue was published. To have this little digital booklet out in cyberspace, with all our pictures, our words, and our art was amazing. I was overflowing with pride. But dammit, it was only online.

Printing is expensive— like, really, really expensive. It took another year, and three more issues of Zapta before I could afford to buy a laser-printer (sadly, that meant procuring employment). I found one “off the back of a truck” from some guy on ***craigslist* (totally not sketchy) and met him at a gas station to pick it up. He helped me cram this giant, 60lb. box into the back of my 1992 Toyota Tercel and miraculously, it fit. I then hauled this giant box up the narrow flight of stairs into my apartment by myself, sweating profusely in unseasonable spring heat. Finally, I had it: the holy grail. A frickin’ laser printer! My heart leapt as the pages of our zine came rolling out, one after another. There she was, Zapta, in the flesh. The thrill was like no other.

But a stack of paper is just that: a stack. In order to be a real-life zine, I needed to bind it. So with a little googling, I decided to try contact cement along the edges of my booklet. After drying overnight, the result was a smooth, bound edge, and a real booklet you could flip through. After 30 more of these bad boys, I was ready to distribute. Luckily, it was just approaching summer, and if you’re from Abbotsford, you know that one of the only thrilling things that occurs in the community happens every Thursday in July: Jam In Jubilee. So, I reached out to the organizers and secured myself a booth to sell my zines. To my surprise, people not only loved it, they actually bought copies.

I hadn’t realized there was actually a market for zines. With the explosion of the internet post-2000, online communities became a relatively viable alternative to share content, express ideas, and find like-minded individuals. While this hasn’t entirely eliminated the importance of zines, it has changed their meaning, and there are still other zine-makers besides myself in the Valley.

But why is it that we are so drawn to a labour-intensive practice, something that doesn’t turn out perfect every time, something we spend hours doing, oftentimes running off of sheer willpower? According to Henny Brown, there is a reason for this.

“I think everything in the world tells us to do things very quickly, but you’re tapping into a community of like-minded people, I think, when you show, share, or distribute zines, where people value individual effort to create something larger with the whole community.”

Henny Brown worked with her Socially Engaged Art Practices (VA 391) class last semester to organize the Fraser Valley Zine Festival at the Clearbrook Library. I was invited to table there and share both Zapta and my personal zines, and was enthralled to connect with so many other print-enthusiasts in the Valley.

“One of the things that I’ve been really interested in with my teaching practice is bringing not only zine-making activity, but the idea of collaborating and organizing and presenting an event to the public with a class. Part of the reason that that felt like a good fit is because we actually have 20 people who’ve registered for the class, who are dedicated to organizing the event…it’s a small student army who are ready to go activate a space.”

For Henny Brown, zines are an accessible vessel for intimate and widely shareable content that is also cost effective. She mentioned that more younger students are becoming aware of zine culture and have a desire to return to traditional techniques, speculating that this stems from a desire for community and countercultural movements.

“I think that’s also what is really causing a bit of the resurgence that I’m noticing right now. People don’t feel like they have a strong sense of community, and zines are a way both in the making and the distribution and sharing, of cultivating more of a sense of community.”

If there’s one thing that making zines has brought me, it’s community. Many of the zine-makers I meet are passionate about living outside the confines of the mainstream; they are questioning our collective morality, and are striving for deeper meaning and connection. They are often inherent activists and advocates for their own communities and for artists in general.

What do a bard and a laser press have in common?

My first introduction to Blue Jay Walker was an absolutely chaotic yet inspiring story that my roommate told me. It was the story of a man who wrote “Bards Eternal,” “the longest physical poem of the 21st century” totalling 9000 lines of straight up scroll written in the middle of Washington Square Park in New York City. Surrounded by swaths of paper, Walker began writing this poem as part of a larger protest of artists responding to the increase of Parks Enforcement Officers and New York City police trying to push out buskers and artists who had made their living there for decades.

An Alberta native, Walker is a full-time artist who is currently posted up in Vancouver, once again causing chaos. I called him on a Friday morning to ask about his latest project Paper Rag, a zine he created in response to the overly digital ways that we consume art.

“[Paper Rag] was created out of … a general frustration with the ways in which art has been forcibly formatted into algorithm based content. My goal with Paper Rag was to extract a lot of the art and ideas and things that are wonderful that we see on the internet all the time, and put it in a space that maybe serves it better and also gives active control back to the readers about what they want to see.”

Walker isn’t the only one feeling this way. In an article for the New York Times, Jenna Wortham states that because of this continuous onslaught of possibilities on the web (described as “a Gutenberg press on steroids”) it’s actually made zines more attractive.

“Producing zines can offer an unexpected respite from the scrutiny on the internet, which can be as oppressive as it is liberating.”

Walker too encourages zines as an alternative medium of sharing art and ideas.

“As artists, we need to not assume that the easiest ways of reaching out to people are the best, and what I mean by that is social media. [It] is the most exponentially advantageous place to reach the most people, but it is always under the control of someone trying to make a profit off of it. We need to actively try and get ourselves off of those platforms, and especially our communities off of those platforms, because when we rely on them, when it comes time to actually mobilize for things, it’s not going to do us any good.”

Walker spoke about how zines have always been in his consciousness and so it was an organic form of creation for him. He’s been mailing out the conveniently letter sized Paper Rag since February of this year, explaining that its small but mighty size is a way to maximize space and minimize printing costs. Walker even pays his contributors a share of the profits. Paid for art? It’s practically unheard of.

But why the heck should anyone even care to make their own zines? According to Walker, it’s a creative way to say a big fuck you to the capitalist system.

“People should be creative, and they should do it in ways that aren’t dictated by corporations who are co-opting it for their own profit. And an amazing way to do that is zines. Zines are malleable, and they’re fantastic to create in a lot of different formats.”

Just as Paper Rag attempts to regain control of the kind of content we consume, Aaron Moran, a zine-maker in the Fraser Valley, argues that zines are a way to democratize art.

“I see zines as activists, a way to support and present diverse perspectives, especially from under-represented or marginalized voices.”

Moran and I met within the confines of an institution. I didn’t think that working for a non-profit organization would connect me with a city administrator who also liked to make zines; but that is Aaron Moran. A long-time maker, Moran got his start as a teenager, being introduced to the zine medium through comics. He has since been curating an ongoing project titled Poor Quality.

“It was about 2017 or so, I started seriously thinking about branding my own zines. I was making a lot of work, just collecting unseen parts of my practice … it was a great way for me to kind of collect all of those pieces that I was working with. I decided on branding my project as Poor Quality, which was a joke on this idea of DIY culture as being in some ways lesser than standard, more common forms of communication like glossy magazines or large media outlets. So it’s a little bit of a joke about that, but also in terms of how they were produced.”

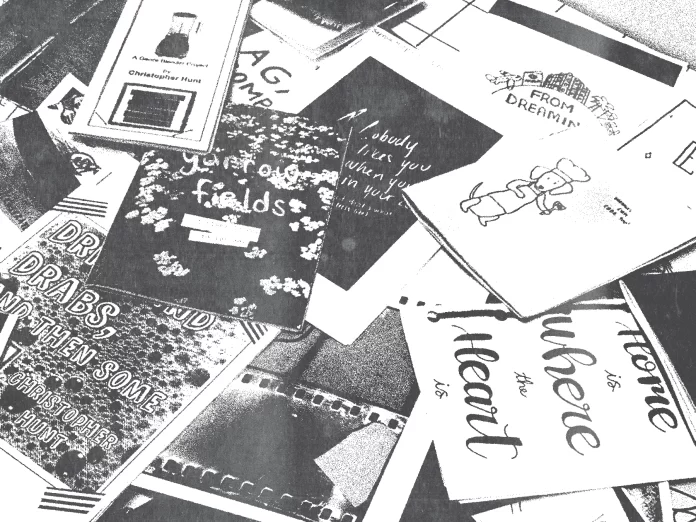

Moran describes Poor Quality as a small press, or laser press, stating that it’s focused on anti-aesthetics and absurdity. All his zines are produced with photocopiers and “low-tech” methods of production, and he encourages artists to compile their work in this format.

“I’m actually interested when people are not designers, and are not super slick with the way they produce things. It stems from this curatorial desire … the zine is just such a great way to disseminate ideas and art. So that’s kind of my drive. It’s really thinking about ways to share work more broadly and having that curatorial focus.”

We both agreed that zine-culture is a beast of its own, and zine-makers always tend to find each other. It’s the beauty of being passionate about something; it finds ways to manifest in your life and draw like-minded individuals toward you. As an administrator and art advocate, Moran tries to cultivate community through creative and professional practices.

“I’m very interested in cultivating the zine community, and I tend to do so through a lot of workshops and presentations wherever possible … I think that those are the ways that I’ve found success and been able to connect with people. You’re showing the wide range of what zines can actually be and what they can look like, and how people can participate in that particular medium.”

It’s been three years and seven issues of Zapta, and I’ve become so grateful to have taken the first step into the world of zine-making. Each issue is intentionally crafted to facilitate both community and self-development, which at the heart of it, are what zines are all about. I’ve made more friendships and connections in the Fraser Valley than I thought possible (and maybe burned a few bridges along the way, but hey — that’s punk, right?). Zapta isn’t just a zine: it’s a community, a hub, a form of activism where we’ve organized and produced events like a concert, a makers’ booth, and an art show. I was even hired by the city to teach zine making workshops — how’s that for an employable skill?

As we venture further into the land of artificial intelligence, algorithmically suggested content, and digital creation, some of us have decided to move backward. To create things with our hands, to meet in person, to take over the dissemination of art and reject the institutionalization of our practices. If you feel stuck, or lost, or frustrated with our technological age, you might just need to sit down with a sharpie, some paper, and photocopier, and tell us how you really feel. Make bad art, make crappy zines, organize, collectivize, and democratize; your community wants to hear what you have to say.

Darien Johnsen is a UFV alumni who obtained her Bachelor of Arts degree with double extended minors in Global Development Studies and Sociology in 2020. She started writing for The Cascade in 2018, taking on the role of features editor shortly after. She’s passionate about justice, sustainable development, and education.