Infographic Brittany Cardinal (The Cascade) – Email

If you’re a registered Canadian voter, a special envelope from the Canadian government probably found its way into your mailbox sometime in the last week or two. Inside is your personalized voter identification card (VIC), which contains information about your riding, dates of advance voting days, and polling hours and locations. It has your name and address printed on it, and in previous years it counted as a piece of ID that you could use to prove your identity at the polls — but if you try to rely on it as a piece of identification this year, you may find yourself unable to vote. That’s only one of the changes presenting a challenge to voters under the new Fair Elections Act.

Bill C-23, also known as the Fair Elections Act, was introduced by the Conservative government on February 4, 2014. Although it consists of eight separate amendments to the Canada Elections Act, the bill’s two most controversial changes were to the requirements for voting: it invalidates voter information cards as a form of identification, and it eliminates the ability to vouch for other voters.

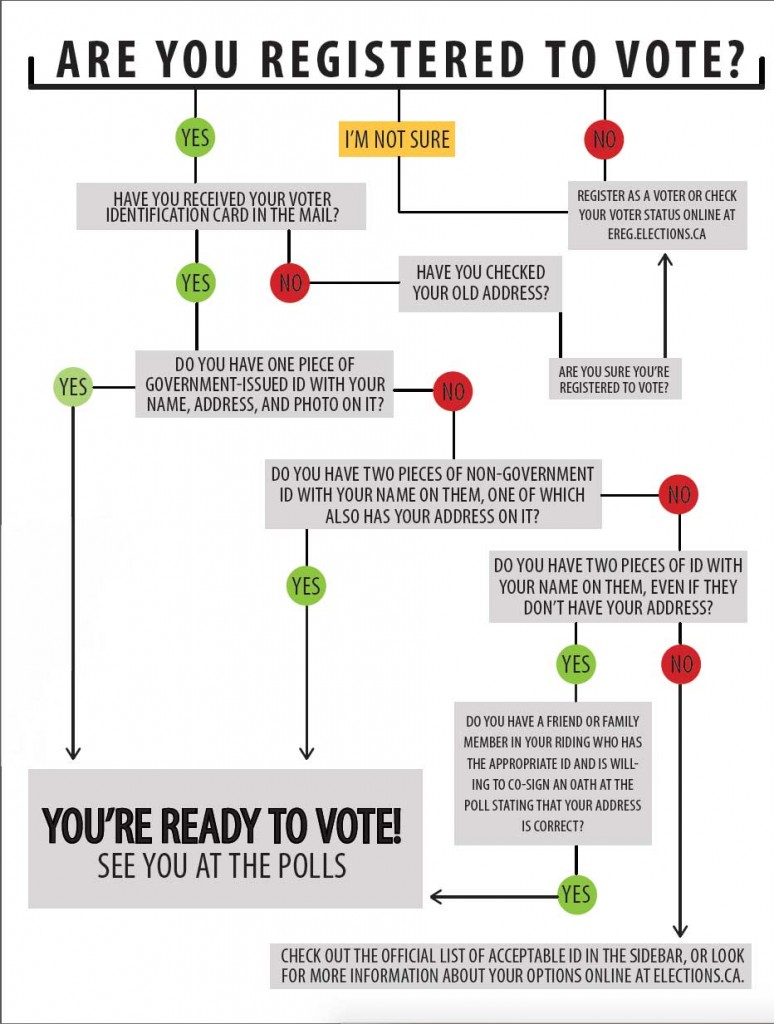

All voters are required to provide proof of identity and proof of address at the polls. Previously, a registered voter with valid ID could vouch for another voter in their riding, thus allowing them to cast a ballot even if they weren’t able to provide sufficient identification. An estimated 120,000 Canadians relied on vouching in the 2011 election — about one per cent of the total 14,720,580 ballots that were cast. Following the Fair Elections Act, this practice is no longer accepted by the government. However, it has been replaced by a similar but more difficult process called attestation: voters who can provide ID with their name but no proof of address can sign a written oath testifying that the address they claim to live at is correct, and then have another registered voter from the same riding with the correct ID co-sign the oath.

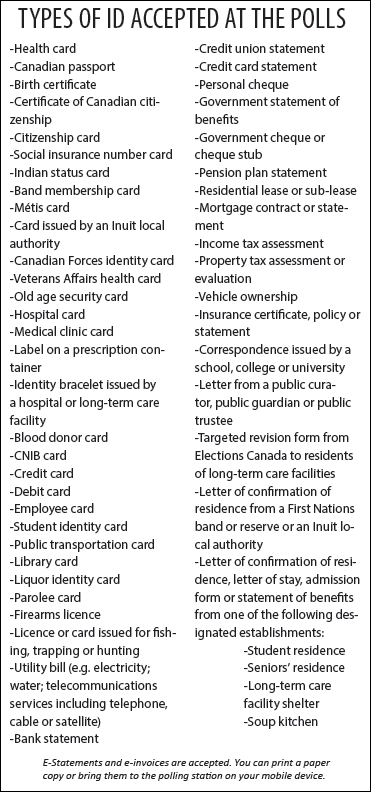

In addition, the VICs that arrive in the mail are no longer acceptable forms of ID. In the 2011 election, approximately 400,000 voters relied on these cards to show proof of identity and address. Under the new rules, voters must provide either one piece of government-issued ID bearing their name, address, and photo, such as a driver’s licence, or two pieces of ID with their name on it, at least one of which must also show proof of address. (See the image below for the full list of acceptable forms of ID.)

These new restrictions on voter identification might not be a problem for most adult Canadian citizens, many of whom will be able to easily produce the required documents, but problems can arise for anyone who does not have a driver’s license, or whose identification has out-of-date information due to recent changes in their address or name. These can include students living on campus; elderly people living in care homes; those who are homeless; newly married people who have recently changed their last names; or those who live in Aboriginal communities where vouching at the polls is common and government ID with a correct address can be difficult to obtain.

The argument for these amendments is that they will prevent voter fraud, but critics have argued that Bill C-23’s restrictions are actually intended to suppress and disenfranchise voters from demographics that tend to vote against the Conservative party. Bilan Arte, national chairwoman of the Canadian Federation of Students (CFS), says that being able to provide proof of address can pose a significant challenge for young people and prevent them from being able to participate in the voting process, which is why it’s important to recognize the VIC as a piece of ID.

“It’s a very significant piece of ID that is utilized by a lot of Canadians, notably young people,” Arte told the Star.

In addition, Elections Canada is no longer mandated to promote voting, and in fact is restricted from doing so. One of the other amendments in the Fair Elections Act targets the content that Elections Canada is permitted to provide to the public; ads announcing the time and location of election polls are allowed, but Elections Canada is no longer permitted to post materials that actively encourage people to vote.

Marc Mayrand, the current chief electoral officer, has voiced concern that the Fair Elections Act and its restrictions on identification and vouching will prevent many voters from participating in the election.

“For some electors, it’s often quite difficult and almost impossible to produce the proper pieces of document to identify themselves and vouching was designed to alleviate these and allow these citizens to cast a ballot,” Mayrand told the National Post.

In July 2015, a coalition consisting of the CFS, the Council of Canadians, and three private voters sought an interim injunction against the Fair Elections Act in an attempt to restore the use of VICs and vouching as methods of providing identification at the polls. The injunction was denied.

So what’s a student, a newlywed, or anyone who has recently changed their address to do? Follow our flowchart on the next page to make sure that you’re registered, have the right ID, and are ready to vote under the new rules of the Fair Elections Act.