The typical commute from my home in Maple Ridge to the Abbotsford campus is roughly 40 km, the majority of which runs along B.C. highways 7 and 11. It’s usually an uneventful drive without that much to see, but occasionally I’ll spot something on the roadside that creates a small pit in my stomach where it resides until the object comes into focus. It’s often some random debris — shreds of tire or fragment of tree — but there are times when it’s tragically not.

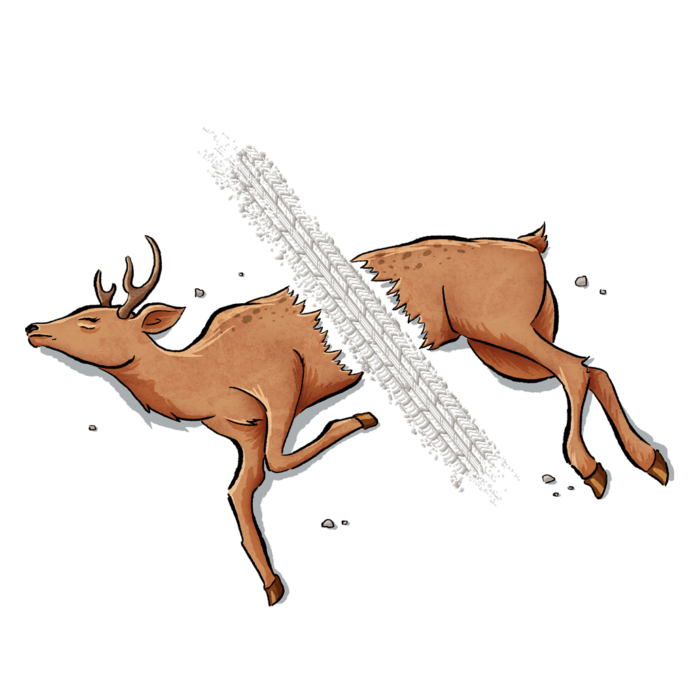

“Roadkill” is the term used to describe the animals who sadly don’t get to see for themselves what that determined chicken was after. As difficult as it can be to witness, the sight of deceased animals on the roadside is often rare, which undersells just how big a problem roads (and the cars that navigate them) are for wildlife. Human thoroughfares often interrupt natural migratory routes, criss-cross feeding grounds, and bisect territories. When animals refuse to engage in a life-and-death game of Frogger, these structures can be impassable barriers locking them into ever-shrinking habitats. Increasingly, more than poaching, deforestation, or pollution, cars are being fingered as a primary culprit in global biodiversity decline.

While we can’t solve an ecological crisis that’s being referred to as the sixth mass-extinction event in our Earth’s history, we can certainly do more to protect the wildlife within our own significant borders — and the template is in Banff.

Banff National Park is home to 44 “wildlife crossing structures” consisting of six overpasses, 38 underpasses, and 82 km of highway fencing. The ambitious project began in 1981 when increased traffic in the region called for twinning that section of the Trans-Canada Highway. Completed in 2014, the ambitious network of natural crossings has become the largest in the world, and is one of the nation’s greatest conservation success stories.

Banff has even become a blueprint for others. As the developing world continues to modernize, and roadways — often arteries of economic growth — expand into natural habitats, motorists are increasingly colliding with wildlife. Brazil’s BR-262, a massive highway that cuts through two of Brazil’s most important ecosystems, is one of the world’s deadliest for wildlife, contributing to the deaths of over a million vertebrate animals in the country — daily. What good is protecting the rainforest if we’ve eradicated all the animals who called it home? And yet it seems that we’ve lost the forest for the trees. Why?

There are things that make humans wonderful creatures, but we’re bad with scale. The suffering of an individual will move us to action more readily than two, and much more than a thousand. It’s a phenomenon known as compassion fade — a term coined by the psychologist Paul Slovic that’s far too complex to explore here — but we best empathize with other individuals. Our ability to care begins to break down when the numbers become abstract. For example: In Newfoundland and Labrador alone, 700 vehicular collisions with moose are reported each year; ICBC records about 1,100 annual animal collisions in the province, whereas one million animals are killed annually on roads in the Greater Toronto Area; drivers in Australia (a country with a population of approximately 26 million people) hit 10 million animals yearly; across North America, up to 340 million birds are hit by cars every year; an estimated 2 billion animals are lost every year to cars. The numbers are so staggering we begin to lose all connection to them.

Consider instead the words of environmental journalist Ben Goldfarb, reporting on roadkill deaths in Brazil: “The victim, six feet from her long snout to her massive tail, lay sprawled on the shoulder in a state of advanced decomposition… I ogled the long broom of a tail, the appendage that this anteater had once wrapped around herself and her pup like a blanket against the chilly Cerrado nights. Now it was limp.”

As a society, we need to not let our empathy for the individual decay into apathy simply because the scale of the problem appears so daunting. Every one of these roads were built with human hands, money, and machines. Would I like to fundamentally redesign our cities and alter our relationship to cars? Absolutely — but in the meantime, building natural corridors is something we can and should do. Once we become aware of the sheer scale of our destruction, it becomes a moral fucking imperative.

This is one of those rare, solvable problems. We are in the midst of a global mass die-off, but we can protect the biodiversity inside our borders. Since Banff constructed its network of wildlife crossings, collisions with animals have decreased by “more than 80 per cent and, for elk and deer alone by more than 96 per cent,” according to Parks Canada.

We can find the money. We’ve incinerated more taxpayer dollars over less — and when you find an issue that hunters and vegans can unite behind — you just can’t put a price on that.

Long ago, when DeLoreans roamed the earth, Brad was born. In accordance with the times, he was raised in the wild every afternoon and weekend until dusk, never becoming so feral that he neglected to rewind his VHS rentals. His historical focus has assured him that civilization peaked with The Simpsons in the mid 90s. When not disappointing his parents, Brad spends his time with his dogs, regretting he didn’t learn typing in high school.