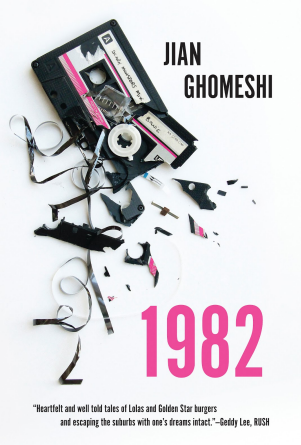

Print Edition: November 7, 2012

“Over the course of 1982, I blossomed from a naive 14-year-old trying to fit in with the cool kids to something much more: a naive, eyeliner-wearing 15-year-old trying to fit in with the cool kids.”

“Over the course of 1982, I blossomed from a naive 14-year-old trying to fit in with the cool kids to something much more: a naive, eyeliner-wearing 15-year-old trying to fit in with the cool kids.”

Jian Ghomeshi wanted to be David Bowie – and who can blame him?

Better known as the host of CBC radio’s cultural-affairs talk show Q and former member of ‘90s folk-rock band Moxy Früvous, Ghomeshi focuses his debut book, a memoir, around his formative fourteenth year. In 1982, the first-time author describes in fresh and exacting terms his attempt to fit in in the deeply conservative (and mostly white) Toronto suburb of Thornhill as a UK-born teenager of Iranian descent.

It’s appropriate for a book that places so much of its focus on music to be structured as a mixtape of songs significant to Ghomeshi’s turbulent and most essential year. This also fits nicely with Ghomeshi’s obsession with making lists, a device he uses at least once per chapter to distill in point form the essential qualities of a particular song, character or fad.

Of his central quest to (a) become David Bowie and (b) win the affections of 17-year-old Wendy, otherwise known as “Female Bowie,” Ghomeshi writes, “I was obsessing over a girl who reminded me of a man who dressed like a girl. These were confusing times.”

1982 is a book about identity, ethnicity, self-discovery, young romance and musical obsession. These big ideas are anchored in symbolic figures that frequently crop up throughout the book: the idol (David Bowie), the dream girl (Wendy), the childhood best friend now relegated to acquaintance (Toke), the new identity (hair gel and eyeliner) and the realm of cool kids (Room 213 – the theatre room). At one point, a beloved and iconic red-and-blue Adidas bag is wrested from Ghomeshi’s grasp and hucked on-stage never to be seen again during a Joan Jett concert, marking a turning point in Ghomeshi’s transition from awkward freshman to arty New Wave sophomore (“My style was a mix between New Wave aspiration and early ‘80s obligation”).

Often, these growing pains are rendered in excruciating and humorous detail, like a 14-year-old Ghomeshi’s first encounter with eyeliner. He steals a pencil of what turns out to be purple eyeliner left behind in Room 213 and meticulously applies copious amounts of the make-up before school one day with utterly predictable results.

Ghomeshi wrangles with his New Wave ambitions and his ethnicity, trying to mesh two seemingly opposing factors in his life. Unlike Ghomeshi, New Wave bands and singers were mostly white and blonde. The 1979 Iranian Revolution had also tainted many North Americans’ opinions of anyone with roots in the nation. Despite spending his childhood in London, Ghomeshi is identified by some of his peers as “Blackie,” “Arab,” and “Paki,” in turn. While he downplays the impact of these remarks, the identity crisis provoked by his membership in the Iranian diaspora runs deep. At one point he admits, “I began to fight a turf war against my own ethnicity.”

Aside from its well-pitched emotional core and easy-going demeanour, 1982 is a pop music addict’s treasure trove. Ghomeshi writes with the same obsessiveness and attention to detail as Nick Hornby in all matters New Wave.

Ghomeshi writes himself like a character in a John Hughes high school movie. He taps into the heart of what it means to be a teenage outcast and a music obsessive that has severe identity issues with remarkable ease and empathy. While Ghomeshi’s rambling, tangent-laden prose might drive some plot junkies around the bend, 1982 is an open and earnestly-delivered investigation into his early teenage years. He brings the same clear-eyed candour that makes him a great interviewer to systematically interrogate his own past. Ghomeshi lets the reader in on his thought process as he writes, sussing out which experiences helped shape who he has become, and why coolness seems so important to a teenager.