Print Edition: February 1, 2012

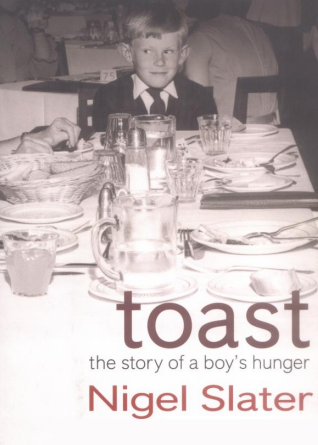

In the 2005 novel Toast: The Story of a Boy’s Hunger, celebrated British chef Nigel Slater pays homage to and puts a spin on the ages-old notion that a way to a man’s heart is through his stomach. Known for his avid support of honest, simple food, Slater tells his story in an honest and simple manner. Toast is a tale told through vignettes, all of which revolve around some element of 1960s British cuisine (be it an idiosyncratic Sunday dinner or a much cherished chocolate bar), and he relates each food item masterfully to the milestones in his own life that have led him to become the person he is now. Chapters are given names such as “Walnut Whip” or “Lemon Meringue.”

In the 2005 novel Toast: The Story of a Boy’s Hunger, celebrated British chef Nigel Slater pays homage to and puts a spin on the ages-old notion that a way to a man’s heart is through his stomach. Known for his avid support of honest, simple food, Slater tells his story in an honest and simple manner. Toast is a tale told through vignettes, all of which revolve around some element of 1960s British cuisine (be it an idiosyncratic Sunday dinner or a much cherished chocolate bar), and he relates each food item masterfully to the milestones in his own life that have led him to become the person he is now. Chapters are given names such as “Walnut Whip” or “Lemon Meringue.”

In between the food featured in Toast, we meet a young Nigel Slater, who at the age of ten is living with an insatiable and seldom satisfied appetite for love, with a father who is best described as distant and troubled, and a warm and affectionate mother who is often taken away by violent fits of asthma. The young Nigel seeks comfort in all things culinary, always having considered the concepts of love and food interchangeable, thus his comfort in the burnt toast proffered by his well meaning but domestically inept mother. “It is impossible not to love someone who makes toast for you.”

When his mother passes away, the chain-smoking, rough talking Joan Potter makes her way into the Slater household and ultimately into Nigel’s father’s bed. Thus begins a whirlwind of blended family tension, silent feuds over lemon meringue pie and familial competition resulting in a slew of almost frenziedly fetishistic descriptions of the desserts and dinners Nigel and Joan cook for the ever-heavier Mr. Slater in conflicting efforts to satisfy that unquenchable thirst for love that resides in those who don’t find it enough.

Readers who open Toast expecting a warm, sugary tale of childhood flour messes and spoon licking will be somewhat surprised at the raw content of the novel, and Slater’s obvious aversion to retelling his experiences through a rose-coloured lens. Toast is rather a very real look at a boy’s formative years, with a real hunger in his heart for absent affection. Slater does not shy away from detailing even the most gritty experiences of his pre-teen and adolescent years – from a somewhat disturbingly nonchalant reference to early incestuous advances by an uncle, to grisly descriptions of vomit that only a 14-year-old boy could muster, to a slightly awkward loss of virginity, and the author’s experimentation with and acceptance of his own homosexuality.

The dishes and candy featured in the book are first, very British, and second, very 1960s. With the majority of college-aged readers having experienced life in neither Britain nor the ‘60s, the food in itself may be difficult to relate to as an exercise in nostalgia. However, younger readers are not to be deferred by the culture and era Slater focuses on, as his strong emotional response to the situations in his life that food plays a role in pervades any social boundaries, and encapsulates readers of any age in a wonderfully recreated diorama of 1960s suburban English life.

Toast seems to be in many ways a therapeutic exercise for Slater, as he looks back with every emotion from regret to impish pride on the experiences that have shaped him into the chef, and ultimately, man that he is. In fact, emotions play such a large role in the book that the foods featured seem to take on more the role of landmarks – fetishized in a sense and revered, especially for their early significance and symbolism. From the book’s namesake burnt toast depicting the genuine efforts of a loving but essentially fading mother, to the numerous chocolates and crèmes laced with adolescent sexual innuendo, to the lemon meringue pie that became such a representation of the power struggle between Joan and the young Nigel.

Slater’s style is atmospheric and easy to read – simple, to the point, and told in first person narrative that is as singular and possessing of a “world revolves around me” mindset that is reminiscent of, one can presume, the 14-year-old boy that Slater is trying to conjure up again and come to terms with.

While in its barest form, Toast: A Story of the Boy’s Hunger is about the food of Slater’s childhood, it is also a brilliantly and tightly crafted peek into the comfy monotony of mid-twentieth century British society, and a wonderful, voyeuristic look into the life of a young boy as he adjusts himself to grief, change, and the ache that is growing up. It is a story steeped in a good amount of melancholy, as nostalgia often is, and sprinkled with a bittersweet dash of hopefulness for the man we already know the young Nigel was to become.