By Kat Marusiak

When you think of the word “comics,” what comes to mind? Colourful images of superheroes fighting villains? Your favourite strip in the newspaper funny pages? Or maybe one of the graphic novels you discussed in your last English course? Probably not that last one, I’m guessing.

For far too long, comics have been relegated to a category below “real” literature: picture books for children who are not yet ready for the complexities of a text-only novel. But comics are capable of being just as deep and complex as any book, and at the same time, just as beautiful and inspiring as a painting or other fine work of art. In a sense, they are both — a bridge that spans the gap, a connection that glues the two genres of art and writing together. They are a unique category all on their own with an almost endlessly wide range of different styles and techniques that combine art and, though there are exceptions, the written word.

WHAT EXACTLY IS A “COMIC”?

Upon trying to define the word “comics,” one will generally find that the genre encompasses so much that trying to define it is an ongoing process. Scott McCloud, comic artist and author of the book Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art, attempts to craft something close to a suitable definition of the genre: “Juxtaposed pictorial and other images in deliberate sequence, intended to convey information and / or to produce an aesthetic response in the viewer.” However, as he points out, this definition still doesn’t cover everything; for example, single-panel comics, which are still instances of the juxtaposition of words and pictures. He adds, “A great majority of modern comics do feature words and pictures in combination and it’s a subject worthy of study, but when used as a definition for comics, I’ve found it to be a little too restrictive for my taste…”

The “comics” genre is constantly changing, evolving, and growing. The combination of pictures and storyteliing has been a part of human society for much longer than most people would imagine. Of course, not everyone would consider things such as ancient Egyptian hieroglyphics (many being able to convey a message, especially in sequence, as opposed to simply representing certain words or letters), or 13th-century German paintings captioned with text, to share similarities with modern comics.

At some point, storytelling and communication began to move away from pictographic representations and toward the written word alone. Pictures are seen as “simpler” and thus suitable only for younger readers, and the fields of literature and art are generally kept distinctly separate. Upon further examination, one can’t help but ask, “Why?” Why do we, as a society, continue to hold this stigma against comics / graphic novels when they can be such thought-provoking and emotionally evocative masterpieces?

SNOOPY VERSUS WOLVERINE

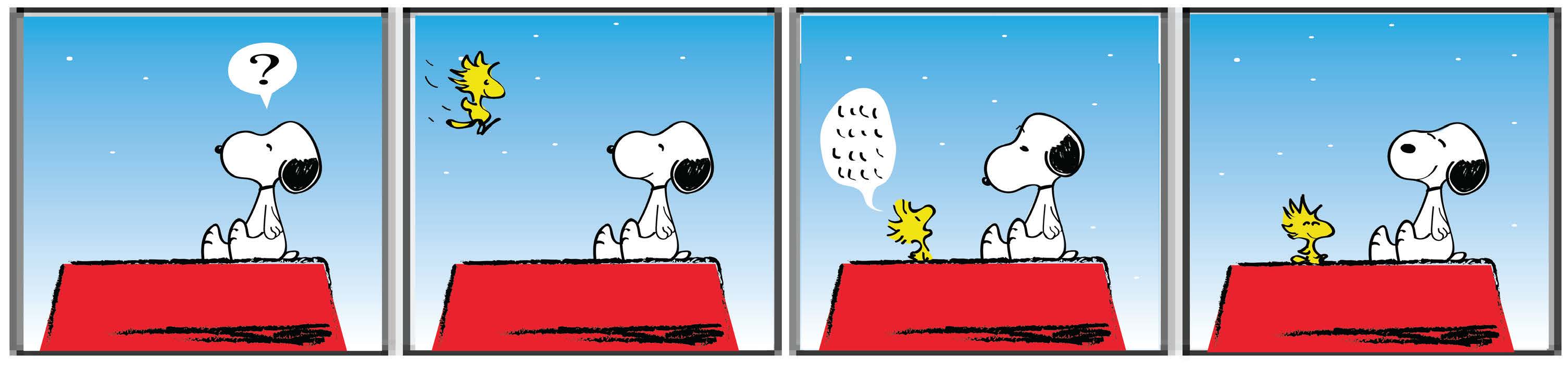

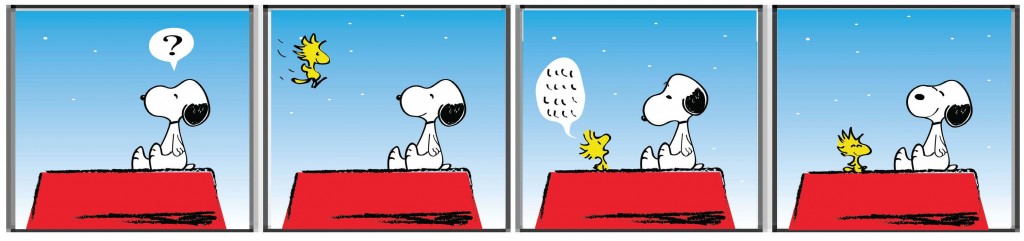

Many people generally lump comics into two main categories: the comic strip, and the comic book; notably those that are often associated with geek culture, about things like heroes, zombies, and other action-packed adventures.

Comic strip series like Garfield are made more for laughs and money, and we don’t exactly see them as particularly mature or mind-expanding. But this doesn’t mean there aren’t also many insightful, well-written comic strips. As a young child, I was enraptured with Calvin’s adventures with his tiger Hobbes — a journey into imagination and self-discovery that I could not only connect to then, but also appreciate again on a whole other level as an adult.

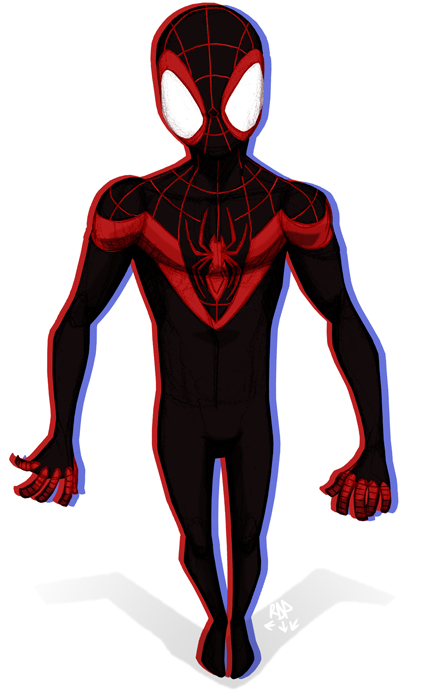

How about comic books / graphic novels? The world of comic books is as diverse as that of text-only novels, ranging from the bright, sometimes gaudy, eye-catching pages of fantastical superhero comics to underground comics (a result of the Comics Code Authority in the ‘50s, which attempted to completely censor and regulate the genre) and more racy images by artists like Robert Crumb, and the life stories and commentary of Harvey Pekar. Stories of fantasy and adventure appeal to all age groups, but there are also the emotional and introspective autobiographic “tragicomics” of Alison Bechdel in which she explores her sexual identity and family history; the brilliantly psychological, deeply thought-provoking works of Alan Moore, which may or may not throw you into a minor existential crisis; and incredible accounts of history, such as Art Spieglman’s Maus, in which he documents the story of his Jewish parents’ survival of the Holocaust, and the effects it had on their lives afterwards.

How about comic books / graphic novels? The world of comic books is as diverse as that of text-only novels, ranging from the bright, sometimes gaudy, eye-catching pages of fantastical superhero comics to underground comics (a result of the Comics Code Authority in the ‘50s, which attempted to completely censor and regulate the genre) and more racy images by artists like Robert Crumb, and the life stories and commentary of Harvey Pekar. Stories of fantasy and adventure appeal to all age groups, but there are also the emotional and introspective autobiographic “tragicomics” of Alison Bechdel in which she explores her sexual identity and family history; the brilliantly psychological, deeply thought-provoking works of Alan Moore, which may or may not throw you into a minor existential crisis; and incredible accounts of history, such as Art Spieglman’s Maus, in which he documents the story of his Jewish parents’ survival of the Holocaust, and the effects it had on their lives afterwards.

Comics come in all shapes and sizes, forms and categories — and they come from all over the world! Most countries have their own classifications and unique designs around the genre due to their individual histories, cultures, and the developments of different styles and subject matters. The simplistic, narrow-minded view many have towards comics is a terrible shame, as they have so much to offer.

THE MARRIAGE OF ART AND STORYTELLING

Comics are not always simple to create. There are many techniques available to comic artists that allow them to create complex, subtle, and intricate designs within their stories, including the shape and number of panels; the use of colour, gradient, and shading; and symbolic objects and themes reoccurring silently that may or may not be noticed upon first read. Think of all the time, thought, and talent that must go into crafting a story, writing the narrative, sequencing the panels, and  drawing the images — that’s no easy task! (This is part of the reason why it’s quite common to see collaborations between authors and illustrators.)

drawing the images — that’s no easy task! (This is part of the reason why it’s quite common to see collaborations between authors and illustrators.)

A BLURRED LINE

The true value of comics is slowly becoming more apparent to people, but the stubborn old stigma about comics being for children still remains, and there is still a long way to go for the genre to be accepted by most literary scholars and writers. Comics are a creature all their own, deserving of a respectable position in the literary arts as a form of storytelling which has much to teach. They cannot be lumped into any one category, and there is constant debate as to just where the blurred line between comics and other forms of art truly lies. As Jonathan Lethem writes in The Best American Comics 2015: “Comics are positioned to bring together the lessons of both the narrative and the visual arts. As such, comics should continue to have the capacity to appear alien and difficult to assimilate within literary publishing. It is an expression of what they are. To expect comics to function merely as colourful, illustrated cousins of conventional narrative fiction is a profound and wasteful act of self-denial.”

So if you’ve never read any comics, or are skeptical of the ability of so many to be a much higher form of literature than they are commonly thought of, I hope you might consider expanding your horizons by taking a closer look at some that may suit your tastes sometime; you may be very pleasantly surprised at just how much of an impact they can make, just how capable they can be of speaking to and moving us, and what a beautiful and effective way they are for people to express themselves and convey their messages to the world.

Teaching comic books as literature: An interview with Ron Sweeney

By Kat Marusiak (The Cascade) – Email

This fall, English instructor Ron Sweeney has been teaching a new English course, ENGL 170: Literature in Context – Understanding Comics, for the first time this semester at UFV`s Abbotsford campus. As the course wraps up, he sat down with The Cascade and talked about what inspired him to start the course, how it’s been going so far, and why comics deserve to be taken seriously as literature.

When did you first start getting into comics?

My main history is not so much as a child, although I remember the Calvin and Hobbes books, Peanuts, the Sunday funnies, and reading that sort of stuff. But I didn’t really read many of the “standard” comics, and where I sort of got into it was much later in grad school actually, where I started looking at “literature and the page” — that was my area of interest — so some of the literature and poetry that did different stuff on the page. And then when I was teaching courses, I would start including some graphic literature on there, and so I actually started with the more autobiographical and quasi-underground kind of stuff. But it was really well received, so I taught stuff like Art Spiegelman’s Maus, and Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home.

Fun Home has been probably the most well-received of the books I’ve taught. But I guess I was looking at stuff that was considered “good” — “graphic literature” as opposed to “the comic book.” So stuff like Watchmen, where it was like, “Oh you have to read this; yes it’s comics, but it’s ‘good!’” and then eventually moved over to realize that there was a whole bunch of popular comic book stuff that was also really good. Some of the stuff like what Chris Ware does, and very spectacular experimentation with story telling, realism, ordinary life, all the way up to the superhero stuff which is [in a hushed tone] actually quite good!

And that helped inspire you to start an actual comics course?

Yes! For most of my fiction courses I’ve included at least one section on comics, and sometimes I make sure if I’m picking an anthology I look for one that has a few little pieces from comics. One of the anthologies I would use would have a chapter from Persepolis by Marjane Satrapi, so there would be a chapter of that, or very often Art Spiegelman’s Prisoner on the Hell Planet might get put in there. I very often included in my novel courses Bechdel’s Fun Home as I mentioned, and the overwhelming response from students has been like, “Where has this been!? Why can’t we do more of this — of comics? Could you do a whole course on this?” And I’d be like, “… Yes I can.” And you know, it took a while. I kept proposing, put together my huge list of comic books, and said that I think this would be a really good course for the department. And now we have 170, and the new overwhelming feedback is, “Could we get an upper level one!?” Hopefully! Hopefully soon! Because you know, there’s so much interesting stuff, and I think it’s a really good challenge for students — the challenge of interpretation of both the fascinating visual and verbal. There’s really important stuff happening in comics, and the debate over whether comics are literature is just … so over, right? It’s been over for decades, and there’s so much literature that still doesn’t get taught and still gets ignored. There’s even questions around things like video games; in my summer class, for the first time, I taught a video game as literature, and we asked that sort of question: “How do we interpret or analyze this stuff? Can we use our literary tools that we’ve learned to analyze and explain plot and character, etc.?” There are all of these genres, and they interact in really interesting ways, and only looking at print I think misses some of the ways in which there is this whole ecology of story telling.

Now that we’re nearing the end of the semester, how do you feel about how the class has gone? Are there any changes you might like to make in the future?

I’m really happy with how it’s gone! I would like to add about 20 books to the syllabus; it’s hard to choose from so many comic books I would like to teach and then have to sort of narrow it down. I think we’re going to be keeping it pretty much the same.

The one thing I will say is that it almost deserves to be split into a part one and part two. You know, “Comics: The Superhero,” or then “Comics: The Ordinary.” Although, of course, then maybe nobody would take the one on comics of the ordinary, and everyone would just go for the superheroes, so it’s a nice way to start.

It is finding that balance between the different genres and styles; there aren’t a lot of anthologies, so in an intro to lit class, you’re trying to show a whole bunch of different fiction, what you very often do is go to the anthology. They have their problems, and ideas of “canon” and stuff like that, but the thing with comics is, you have Best American Comics, but there’s no “Best American Comics Comics.” The very best of the best of! That might be something I’d be interested in.

But it remains that it is an introduction, and the thing I’m the most impressed with in the class is the sharing that goes along in comics. People bringing books to class and sharing books with each other, sharing books with me, me sharing books with people. And that seems to be a big part of the culture, like, “Hey, have you seen this?!” And people bringing their experiences. People who haven’t read many comics getting to see what it’s like.

The other thing I need to eventually become an expert on is non-Western comics and non-English comics. Eventually, I think that would be added to the course. I think there could be some really interesting comics courses that could be offered here, and hope they do get offered here eventually.

If you could only recommend a few artists or titles to someone who’s just getting into comics, what would you recommend? What are your favourites?

Well, when I’m recommending books to anyone, I tend to ask more questions before — so for example, if you’re interested in superheroes you should absolutely be reading Ms. Marvel. Go back and check out some of Gale Simmons’ work. She did a fabulous job of drawing attention to the mistreatment of female superheroes, and has written some great stuff.

The other one then I would always recommend is Alison Bechdel. Read Fun Home. Fun Home is fantastic. I also recommend —with some trepidation because of the super violent content — but some of the stuff that’s coming out of Image Comics just blows me away. And then the absolute — if you’re interested in all of the possibilities of comics — then Chris Ware is the person to turn to. He does some of the most interesting, ordinary, everyday-life comics. Ware also explores comics culture in really fascinating ways, explores nostalgia, explores the city, explores the way in which comics work — so things like moving around the page in very different ways, forcing you to try to figure out how to read a Chris Ware comic. The first time you read one you may be very frustrated because you’re not used to what’s going on, or finding your way around the page in quite the same way. There are so many good artists working today that you come across certain artists where you’re like, “I can’t believe I missed this person!”

Any last things you’d like to say about the class in closing?

Take English 170! You will learn to understand comics! It’s a really fun course, and it’s a really serious course, and I think you’ll be looking at comics in a whole new way if you come take it. There are some really interesting questions around interpretation, you’ll get a little bit of the history of comics, understand why comics are often associated with children’s reading, and what’s happening in contemporary comics. And you’ll also get to share your own ideas and experiences of reading comics.

Kat Marusiak is enrolled in English 170 this semester.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.