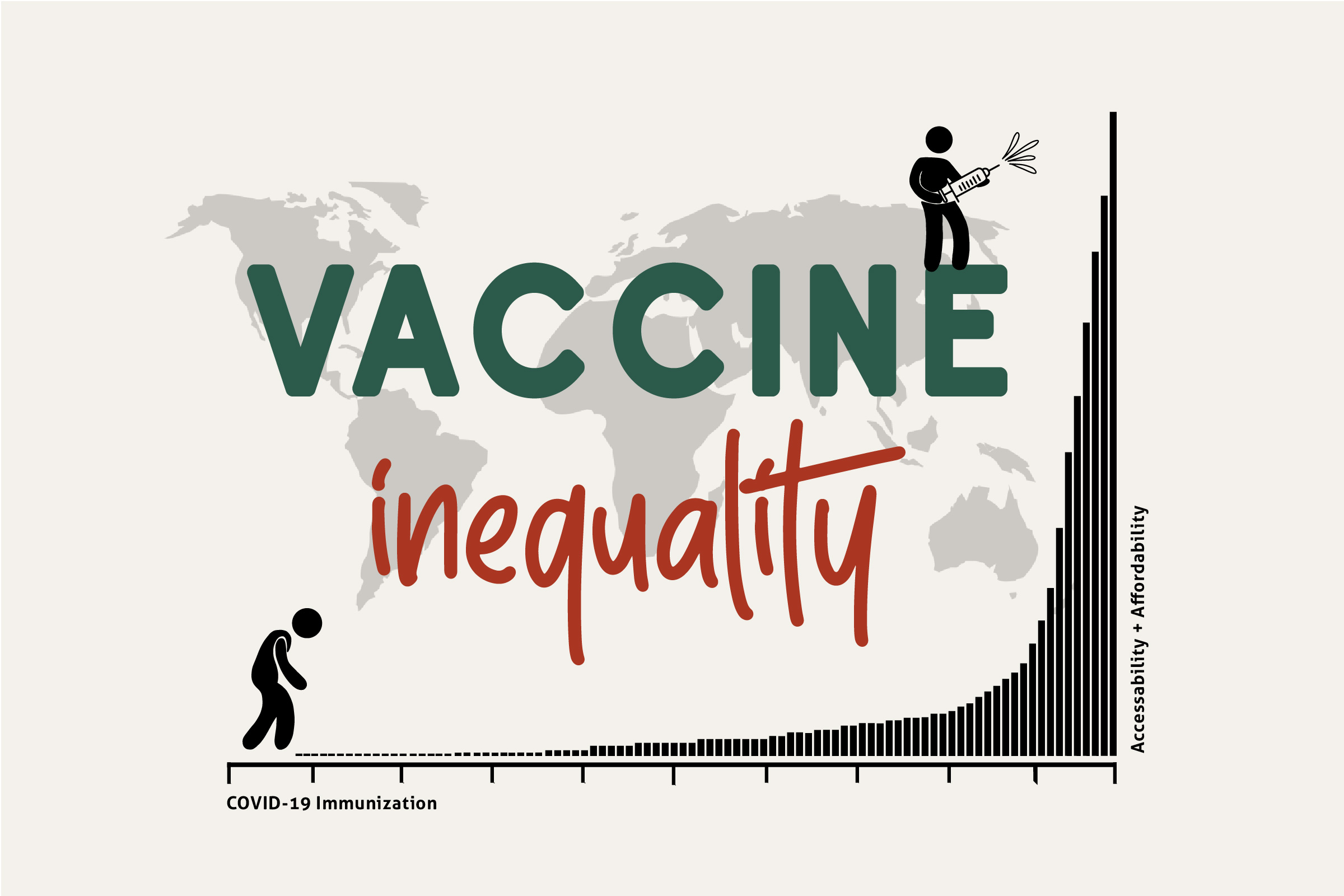

Questioning the global accessibility of the life-saving vaccine

Since the COVID-19 outbreak was declared a public health emergency, daily life has been drastically disrupted. Masks are a new necessity, temperature checking is done on the regular, and the words “social distancing” have ingrained themselves into everyday vocabulary. Although we’ve had to say goodbye to our ways of pre-pandemic life, there’s a general notion that once a COVID-19 vaccine is made available, things will return to a state of post-pandemic normality. But the question becomes this: just because there’s a vaccine available, will everyone have equal and affordable access to it?

Distressingly, there has been minimal discussion about how the vaccine will be made accessible on a global scale. The race for a COVID-19 vaccine has been focused on how it can be made available as quickly as possible, but without open dialogue about pricing, many vulnerable populations could be left behind. Now’s the time to be questioning the privatization of health care in the U.S., health-care barriers that developing nations face, and the pricing of life-saving drugs.

Accessibility in developed nations

When thinking of communities that might have trouble accessing health care, those living in North America need only look to the U.S., infamous for its privatization of health care. This means that doctor appointments, hospital visits, and prescription drugs aren’t covered by public funding and end up costing a pretty penny to Americans looking for basic health-care services.

Few know this better than diabetics like Sabryna Renaud, a health-care worker from South Carolina. As a type-1 diabetic, her pancreas doesn’t produce any insulin hormone, a necessary molecule for regulating nutrients like glucose (sugar) in the body. What this means is Renaud needs to constantly monitor her blood sugar, correcting it with food or injectable insulin as needed. Since moving to a different state and taking on a full-time job, Renaud is no longer eligible for the federal, low-income health insurance called Medicaid and struggles to pay for insulin and appointments with diabetes specialists.

To cope with the overwhelming costs of insulin supplies, which would run Renaud $500 to $1200 a month out-of-pocket, she and many others have been leaning on a community of diabetics using the #Insulin4all hashtag on Twitter. Not only is this hashtag an advocacy campaign for affordable insulin, but it’s also a place where diabetics can donate and share supplies. Within the hashtag, there’s an overwhelming number of diabetics who are able to rely on each other rather than the U.S. health-care system.

As Renaud put it: “You pay for insurance, but you’re still going to have co-pays and everything with that. You have to decide: do you want to pay for your health care, or do you want to pay for your home, your car, other expenses? You have to choose either your life or something else in your life.”

It’s difficult for Renaud to have confidence in a health-care system where bankruptcies are regularly medical-related and citizens are denied life-saving treatments like insulin if they can’t afford them. There’s good news, though: the U.S. government has invested in 100 million doses of a potential COVID-19 vaccine in the works by Pfizer and BioNTech. If a vaccine comes out of the two partnering companies, it will be made available to Americans at no cost, according to the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services (HHS) news release. The cost of administering the vaccine, however, can be charged to insurers.

This is a major step in the right direction although it could be considered vaccine nationalism — a phenomenon of countries buying up doses of future COVID-19 vaccines for their respective populations. Pfizer and BioNTech won’t necessarily produce a FDA-approved vaccine, but if they do, the U.S. government has a solid agreement in place to ensure doses for a sizable portion of its population. The HHS has invested millions in other promising vaccine candidates, but no further funding models have been discussed.

The downside? Nothing’s been mentioned about the 27.5 million Americans living without health insurance (according to statistics from the United States Census Bureau, which could be a low estimate) or the millions of others losing health coverage due to pandemic-related unemployment. The cost of injections billed to insurers has also been criticized, in the case of the flu shot, to be passed along to consumers later through higher insurance premiums. The costs of treatment and hospitalization for COVID-19 in the U.S. are also a major issue. Take Remdesivir, for example, a drug that’s been seen to lower recovery time in COVID-19 patients and was announced in June to cost $2,340 for a five-day course. This price has been praised by some as altruistic and heavily criticized by others.

Accessibility in developing nations

When it comes to low- and middle-income countries having access to a COVID-19 vaccine, the largest public-private partnership committed to making it happen is GAVI. This international organization focuses on vaccine alliances that share the cost that developing countries pay for vaccines. COVID-19 has been no exception.

The Access to COVID-19 Tools (ACT) Accelerator is a global collaboration organized by GAVI that aims to support development and distribution of tests, treatments, and vaccines. Under the project name COVAX, GAVI will be pooling resources from participating countries to invest in a range of COVID-19 vaccine candidates. When doses of a successful vaccine are available, GAVI will immediately distribute them to developed and developing nations alike. This means that both self-financing and GAVI-funded countries are guaranteed enough doses to immunize at least 20 per cent of their population.

Unfortunately, COVAX has been criticized for how it’s chosen to incentivize its program. While it advertises its desire for equitable distribution of vaccines, it also allows self-financing nations to secure their own partnerships with private companies while investing in COVAX. This means that independent contracts between countries and companies could deplete the total number of doses available for COVAX to distribute to developing nations. It also allows these higher-income countries to double-dip — to have their independently bought doses as well as those supplied by COVAX.

The other issue with distributing a vaccine to developing nations is potential barriers to access. Depending on what form the final vaccine takes, low- and middle-income countries may need to adapt. For example, if the vaccine ends up being an injectable, it could require being kept at a low temperature, which requires additional equipment to support.

Dr. Omoniyi Oluwadamilola is a Nigerian pediatrician who recently co-authored a review study on childhood immunization rates in low- and middle-income countries. On the cost of vaccines from government health facilities in these countries, she explains: “The out-of-pocket cost to the people is not the cost of getting the vaccine, but rather it’s the cost of being at the point of [contact].” While the vaccine may be available for free at public facilities (and for a fee at those that are private), there could still be barriers that prevent patients from making their way to a clinic, like transportation or lost income if they must take time off work.

For COVID-19 vaccinations, Dr. Oluwadamilola emphasizes meeting people where they’re at, whether that be at home, public spaces, or at the workplace. There’s also the essential factor of communication and education. A lack of awareness and false beliefs within a population can negatively affect immunization rates, and COVID-19 is no stranger to conspiracy theories.

“Communication will be very key here. It will be so important to reach out to people, to talk to them about the benefits. You tell them why it’s important to get the vaccine, to alleviate their fears. There’s been a lot of suspicions about vaccinations over the years … There are some that don’t even believe COVID-19 is really in Nigeria, for example.”

Infrastructure in countless countries that vaccinate for polio has already been established by nonprofit organizations like Rotary International, of which Carol Tichelman is the 2020-21 district governor for the 5050 area. While most of the year Tichelman is local to Chilliwack, she’s also worked to deliver Rotary services to Ethiopia and Uganda, including participating in eight National Immunization Days for polio.

“Rotary has helped establish a lot of health-care systems in developing countries. There are polio eradication employees and coordinators in most developing countries, and a lot of them have been repurposed … We have the infrastructure in place for the delivery of polio vaccines in countries all over the world. That infrastructure will definitely be used for the delivery of a COVID-19 vaccine when we’re blessed to have one.”

Even with established infrastructure, in Tichelman’s experience there were still barriers to access for delivering the polio vaccine; for example, if a woman was without her husband, Tichelman found she was often reluctant to allow the immunization of her children. Tichelman also witnessed health-care workers having to travel between cities in armed vehicles for protection on National Immunization Days. The importance here is that while health-care workers in developing nations can leverage a country’s previously built infrastructure, they will also have to learn from the hurdles that other immunization initiatives have faced.

The science behind vaccines

In order to understand how and why life-saving treatments are priced the way they are, we have to understand the basics of drug research and development, the first step of which is discovery and development: what drug compound are we looking at and what information can we gather about it through experiments? These experiments extend into preclinical research — meaning research before the drug is tested on humans. If the drug seems promising, it moves on to clinical research. Clinical research is made up of clinical trials, which are experiments that focus on humans. The trials come in three consecutive phases that take years to fully complete before the product can be approved for the market.

Dr. Martin Wehling is an internist, cardiologist, and clinical pharmacologist who’s also worked as the director of translational medicine for AstraZeneca, a major pharmaceutical company. Translational medicine means “how to facilitate research from mice to men,” according to Dr. Wehling.

What Dr. Wehling calls for in his recently published paper in the European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology is a human testing scheme that exponentially grows in participant numbers every few weeks, is adaptive, and combines all the phases together. He admits it’s unconventional, but given the demand for the vaccine and the cost of potential human lives, it feels necessary. This is already being seen to some extent in COVID-19 vaccines being developed, where clinical trial phases are being combined and sped up.

Only seven per cent of all drugs entering clinical trials are successfully approved for market use by the FDA. As of September, there are currently 46 COVID-19 vaccine candidates, 29 of which are in clinical trials. Seeing such quick progress being made is promising, but also not a guarantee that the world will have a COVID-19 vaccine by the end of the year.

As Dr. Wehling puts it: “The systems of how to design trials have to be adapted to the demand. As everybody knows, this vaccine is needed desperately and soon … Normally, without that tremendous pressure, [clinical trials] could take five years or eight years to be properly conducted.”

When it comes to types of COVID-19 vaccines in the works, Ha et al. wrote the journal article, “The Current Update of Vaccines for SARS-CoV-2,” finding that the three main approaches have been whole virus, subunit, and nucleic acid.

In whole-virus vaccines, the patient can be exposed to a virus that can still function inside the body but has been altered so it can’t cause damage. An example is the vaccine being developed by the University of Oxford, which is a safe adenovirus that produces a similar spike protein to COVID-19. If the patient encounters the COVID-19 virus later, the immune system will more easily recognize the spike protein and mount an attack against it.

As for subunit vaccines, they focus on exposing the patient to only a specific part of the virus, like the spike protein. Because COVID-19’s spike protein is unique, it allows the immune system to strongly target an important component of the virus.

Lastly, nucleic acid vaccines deliver a packet of genetic material from the virus, whether that be DNA or its counterpart that leads to protein production, RNA. An example would be if the DNA for the spike protein was used, entering the body and serving as the blueprints to create the spike protein, which is then recognized by the immune system and destroyed. This helps employ a wider and stronger immune response than a subunit vaccine.

The pricing thereafter

Often cited in determining pricing of pharmaceuticals is the value that the drug provides and its competition on the market as well as the time, effort, and money put into its research and development. The average cost of research and development for FDA-approved drugs has been estimated to be $2-3 billion.

The COVID-19 vaccine, and pandemic at large, is an opportunity for law makers and leaders to make major changes to health-care systems globally. While Canada has regulations on drug pricing, the U.S. doesn’t, which allows for market monopolies to occur. Donald Trump, the current president of the U.S., recently announced steps toward breaking some of these monopolies, although many won’t be fully enacted before election day. There have also been calls for coordinated drug price regulation on an international level, an idea still in its infancy but nonetheless a tangible goal to work toward.

Dr. Mixæl Laufer is the spokesperson and founder of Four Thieves Vinegar, a collective that focuses on biohacking pharmaceuticals by connecting disenfranchised patients with free, open-source information on how to make medicine at home.

As far as drug pricing during a pandemic goes, Dr. Laufer says: “When we look at, as people term it, ‘Big Pharma,’ they’re not immoral per se — they’re amoral. It’s an important differentiation to make because you don’t have a bunch of people sitting in a back room rubbing their hands together saying ‘How can we make people suffer?’ What you have is a bunch of people sitting in a room saying ‘Well, how do we profit from this as much as possible?’”

In February, the Four Thieves collective released a free pandemic survival guide as a response to COVID-19 that outlined how citizens could protect themselves and care for those who are ill.

As for potentially working on biohacking a COVID-19 treatment like Remdesivir, Dr. Laufer says: “We’re very much ready as soon as something gets sufficiently established that would be a fairly universal treatment — to hijack it. The problem is that nothing has proven to be that good yet.”

Meanwhile, more than 140 world leaders have signed an open letter calling for governments to band together for a people’s vaccine against COVID-19. This means working toward a vaccine that’s patent-free, mass-produced, and distributed free of charge. The letter stands as an open acknowledgement that this pandemic requires committing to a worldwide pool of COVID-19 knowledge and technology.

The idea to forfeit patents and intellectual property, believe it or not, is not unheard of. For polio, neither the injectable nor the oral vaccine are patented. This means other companies were able to reproduce and distribute the vaccine right away, offering competitive prices that eventually allowed Rotary International to fundraise and start a polio eradication initiative. In a similar fashion, the patent rights for insulin were symbolically sold to the University of Toronto in 1923 for $1 to each creator. With the development of a vaccine for COVID-19, it stands to reason that a similar forfeiting of rights is reasonable and, most importantly, feasible.

Public scrutiny for price gouging of COVID-19 treatments and vaccines will no doubt be swift and harsh, and while that doesn’t ensure a vaccine will be priced in a way that’s globally accessible, there’s been progress. The purchase of 100 million doses of a potential vaccine by the U.S. government is a big step in the right direction of government units purchasing treatments on behalf of Americans — to the detriment, perhaps, of depleting the global availability of doses for partnerships like COVAX. It proves that it’s possible for the U.S. to do, and that more people need to fight for their right to health care with their political power and voice.

What’s made the COVID-19 pandemic so uniquely terrifying is how little we know about the virus. The last thing we want to worry about is gaining access to the supposed solution to this problem — the vaccine. While the upcoming COVID-19 vaccine could very well be affordable, the current uncertainty opens up a larger discussion of public health, trust, and who’s calling the shots when it comes to health care. If there’s anything positive to come out of this pandemic, it will be that the world at large is beginning to acknowledge the gaps in health-care systems on a global scale: the privatization of health care, infrastructure barriers, and pharmaceutical price gouging.

Illustration: Shara Hamed/The Cascade

Chandy is a biology major/chemistry minor who's been a staff writer, Arts editor, and Managing Editor at The Cascade. She began writing in elementary school when she produced Tamagotchi fanfiction to show her peers at school -- she now lives in fear that this may have been her creative peak.