Due to human-caused climate change and the destruction and pollution of habitat, animal and plant species are becoming extinct and we are losing precious biodiversity at an unprecedented rate. According to a report by the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES), 20 per cent of all native plant and animal species around the world have been lost in the last 100 years. These numbers are only projected to accelerate — we’re talking about a mass-extinction-level event. Experts suggest that unless governments take protective measures, one million species are threatened by extinction.

Over 230 species are at risk in B.C.’s Southern Coast (the districts of Chilliwack, Squamish, and the Sunshine Coast). There are several animal species at risk right here in our backyards, including the great blue heron, Oregon forestsnail, Oregon spotted frog, western painted turtle, white sturgeon, northern spotted owl, and pacific water shrew. The plant species of tall bugbane, poor pocket moss, phantom orchid, and streambank lupine are also endangered. While these are not megafauna that get mass amounts of media attention and protests, like old growth forests or Northern White Rhinos, it is still devastating to know that if we do not prioritize their conservation, they will be lost for the generations yet to come. We will never see them again.

“We are ultimately controlling the fate of what future generations get to see and enjoy and experience,” said Aleesha Switzer, project biologist at the Fraser Valley Conservancy and UFV alum.

Habitat loss, degradation, and fragmentation are the primary threats to these species, as more habitat gets lost or destroyed due to urbanization, forestry, and agriculture, especially the wetlands, where so many endangered species reside. It is estimated that 87 per cent of all wetlands in the Lower Mainland were lost between the 1820s and 1990s. Since the arrival of European settlers in the Valley, the landscape has been dramatically altered to support agriculture and urban infrastructure to the detriment of the native species and the ecosystems they depend upon.

You can find these species at risk in your own backyard if you pay close enough attention. We’re going to profile just a few species that are at risk here in the Valley:

Oregon Spotted Frog (Rana pretiosa)

There are currently only six small populations of these amphibians left in the Fraser Valley, which make them one of the most at-risk species of extinction in the Fraser Valley. The main threats to their survival include the loss of their wetland habitat and the predatory nature of the invasive bullfrog species who compete for resources.

“[The Oregon spotted frog] represents the type of ecosystem that we used to have dominating the Fraser Valley lowlands: that shallow marsh ecosystem,” said Switzer. “This frog is still holding on and it’s almost beckoning us to return to some sort of balance here with the water, with the creatures that live here.”

This frog that represents the beautiful marshland that once dominated the Fraser Valley landscape is precariously sitting on the edge of extinction. It is estimated that there is a 60 per cent chance of five of these populations going extinct in the next decade.

The Fraser Valley Conservancy’s Precious Frog program wants to make sure this doesn’t happen. The program works towards habitat restoration and enhancement, research, and education. If you have seen or heard a frog in your area, you are encouraged to fill out a frog finder form on the Fraser Valley Conservancy’s website or iNaturalist. This form will help identify potentially hidden populations of amphibians and aid in the research of biologists who are working to protect this species.

Another threat to amphibians are fungal diseases like chytridiomycosis, which affects an estimated 30 per cent of the world’s amphibians. Switzer said that they recently had the bacterial communities of the Oregon spotted frog sampled in a lab, and these researchers discovered that their skin contains a bacteria culture that creates a peptide, an antifungal that can control this fungus that has devastated amphibian populations around the world. This is an example of the vast knowledge and medicines these species contain in their very DNA which will be lost, never to be discovered, if they go extinct.

Identification: They can range in color from reddish-brown to olive to tan and have irregular black spots on their bodies. There is a light stripe that runs from their upper lip to their shoulder, their eyes are pointed upward, and their snouts are slightly pointed.

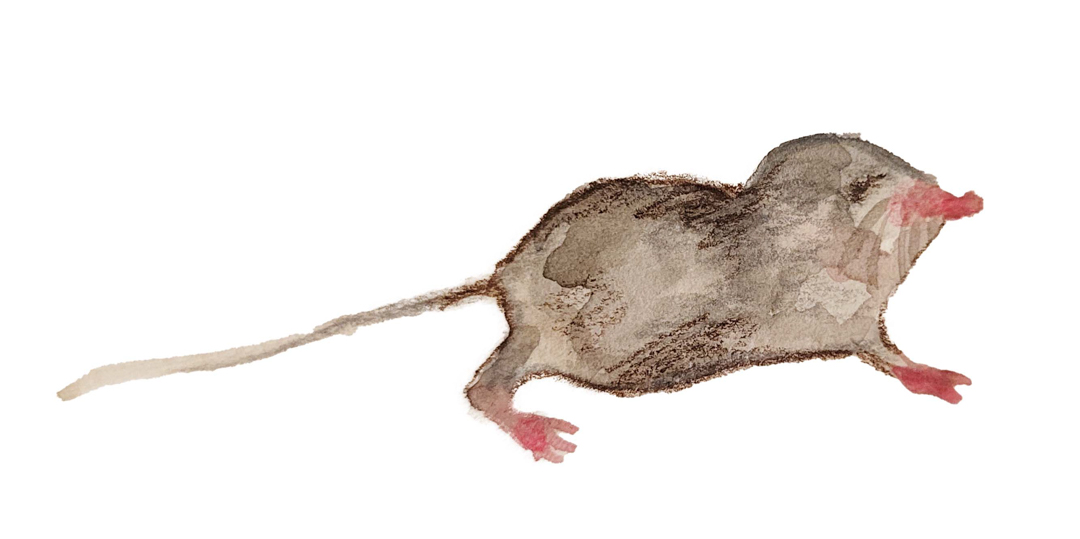

Pacific Water Shrew (Sorex bendirii)

This little guy is the world’s smallest diving mammal, who lives a semi-aquatic lifestyle and can even run on the surface of the water for up to five beautiful seconds. These little creatures live in riparian areas (the vegetation that grows along the edge of a natural body of water) for the duration of their lives — spanning 1.5 years — and they survive on a diet of insects and small invertebrates like snails, mollusks, and slugs. They use their sensitive whiskers to detect prey underwater, where they can forage for up to 3.5 minutes.

There is a story told by the Stó:l? people about the Pacific water shrew, otherwise known as the hiháwt. A brother and sister shrew were running over some logs as they were playing in the creek, and a maple seedling pierced the foot of the sister shrew. A forest snail came over to the pair to help, and brother shrew noticed the forest snail had a rash, to which he offered alder bark to make a tea that would help heal him. Later that night, the forest snail drank the tea and prayed to help the shrews when a vision came to him. He snuck into their home inside a log while they were sleeping, plucked the fine hair off his own shell, rubbed it until it became stiff, and placed one on each of their feet. With these stiff hairs on their feet, the shrews were able to run over the surface of the water instead of having to cross over logs.

There are few records that exist of this rare and elusive species, and more research is needed to determine the current population size.

Identification: It is rare that you will see this tiny mammal weighing in at 10-20 grams, just about 17 cm long and 7 cm tall. However, should you be so blessed, they have dark-brown to black velvety fur, with a very pointed snout decorated with long whiskers, and a long, thin, brown tail.

Oregon Forestsnail (Allogona townsendiana)

This humble yet beautiful little snail is one of the few native species of terrestrial gastropods we have left in British Columbia. Unlike invasive species, these guys don’t want to eat your lettuce or munch on your garden; they just want to hang out in the forest and live their best lives eating decaying vegetation. These hermaphrodites play a crucial role in the forest ecosystem by aiding in decomposition and dispersing spores and seeds. If you have any trees or stinging nettle (their favorite snack) in your backyard, try going out and looking for them; I bet they’re hanging out right in your backyard, ready to be discovered.

“I love the Oregon forestsnail,” said Switzer. “My favorite thing about the Oregon forestsnail is just how easily it kind of slips under the radar. It’s one of those species that is just on the ground, not moving around, not doing anything. But there it is, on the trail, walking in the forest — an endangered species. It’s not trying to make itself known, it’s not flashy, but when you get to see it and hold it, it’s kind of special.”

Climate change is another threat to native terrestrial gastropods that has been largely understudied. Extreme weather events like droughts and heatwaves will degrade the moist habitat they need to survive. Oregon Forestsnails are particularly sensitive to local temperatures, and when these conditions are unfavorable, it limits their movement by drying out their secretions.

Identification: Their shell’s diameter is about 2.8 to 3.5 cm and its colour can range from gold to reddish or dark brown. Their shell has a thick, white rim that flares upward and has thin bands spanning across each whirl on the shell, giving them a textured look.

Great Blue Heron (Ardea herodias fannini)

If there is one animal on this list I know you’ve seen at least once before, it’s this tall, wading bird with beautiful blue plumage. While this bird with legs that go on for days is not on the “red list” of endangered species, it is on the “blue list” of special concern, meaning they’re still vulnerable to extinction. These birds group together in major nesting colonies known as heronries. The Great Blue Heron Nature Reserve in Chilliwack is made up of 325 acres of wetland off the Vedder River and is home to a large nesting colony of Pacific Great Blue Herons.

While some sources suggest that bald eagle predation is a threat to the great blue herons, Camille Coray, executive director of the Great Blue Heron Nature Reserve Society, reveled in the relationship that she observed between eagles and herons in the reserve. She said the herons would actually build their nest closer to these predators in a sort of symbiotic relationship of protection.

“Basically, the eagles are very territorial and they will eat other raptors — definitely other eagles — that are in the area,” said Coray. “So for the [heron] parents, it’s a really good thing to have a pair of nesting eagles within 200 meters of their colony. They have to be at least that close in order to offer the level of protection that they’re looking for. They will, of course, get preyed on to some degree by the eagles. But the level of predation from just a pair of eagles is far less than what the level of predation would be from every eagle in the area.”

Herons themselves are one of the top predators on the reserve, according to Coray, which makes them a keystone species that keep populations of other species in balance.

The biggest threat to great blue herons, like many other endangered species on this list, is habitat destruction and the lack of legislation that is required to keep this habitat intact. Coray recalled phone calls she would receive from people who watched developers tear down trees with heron nests in them. There is a stunning lack of laws for developers to follow to ensure their projects aren’t pushing animals out of habitats.

“Wetland habitat is one of the most threatened habitats as well as one of the most productive habitats when it comes to housing species,” said Coray, who listed all of the endangered species that could be found within the 325 acre reserve, including the Western Painted Turtle, the Northern Red-legged frog, the Oregon forestsnail, and the Northern Goshawk.

To get involved at the heron reserve, or if you want to report sightings of heron colonies that may or may not already be mapped in the Lower Mainland, contact Camille Coray at herons@shawbiz.ca. You can also visit their website, chilliwackblueheron.com, for more information.

Identification: They are tall, long legged birds with an S-shaped neck. They have steel blue-grey feathers, with darker blue flight and tail feathers. Their long, thick bill is yellow and black, and the head and face are white.

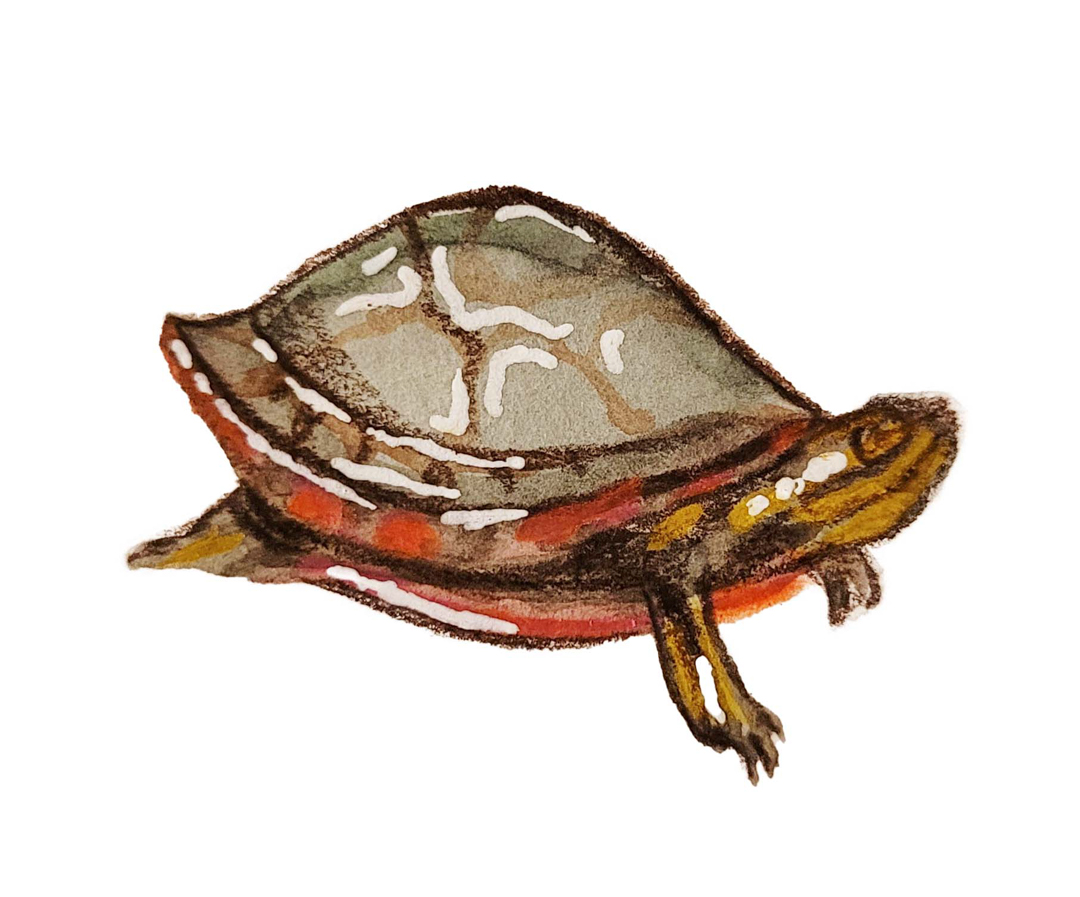

Western Painted Turtle (Chrysemys picta)

One of the longest-living reptiles in North America, the Western Painted Turtle can live over thirty years in the right conditions and is the last remaining native freshwater turtle species on the B.C. coast. A fun fact about these turtles is that the temperature of their eggs in the incubation period determines whether their sex will be male or female.

“Every single turtle has the genetic capability of being a male or a female turtle. It’s decided by temperature,” said Andrea Gielens, lead biologist at Wildlife Preservation Canada and adjunct professor at UFV. “It’s actually decided in the nest on one day of their incubation; if the nest or hatchlings of eggs are warm, then they become females. If they’re cooler then they become males … So, if we have a really warm summer, then we’ll probably get mostly females; in a really cool summer we’ll get mostly males.”

Gielens leads the Fraser Valley Wetland Recovery Program, which includes a captive breeding and release program for the Western Painted Turtle and the Oregon Spotted Frog. Her work involves tracking where female turtles nest and protecting the eggs by putting a cage over them to ensure they cannot be dug up or stepped on. For particularly vulnerable nests that are highly likely to be disturbed, they take the eggs into captivity to incubate them and raise them up as babies until they are about 30 grams or three inches long, at which point they release them. Gielens said some of the baby turtles are about the size of a nickel and grow very slowly over the course of one or two years.

“These turtles provide really important roles in the ecosystem,” said Gielens. “Turtles are great recyclers. They’re detritus feeders. They maintain the ecosystem by being that conduit of composting. Any fish that you get in the environment, those are gonna get gobbled up by turtles right away, along with all the plant material, and they help to get insects in control.”

Western Painted Turtles are the last native species of aquatic turtles we have in B.C. They are another wetland species whose habitat is threatened by urbanization, and their migration corridors that span across roadways only increase their mortality rate. Invasive plant and animal species, like the Slider turtle, compete for resources, and roots from some invasive plant species can even penetrate and entangle the nesting area and eggs of these reptiles.

“The best thing people can do is realize that there are turtles out there that are native species that nest on sandy beaches,” said Gielens. “So, if there’s an area where there are turtles in the water, and there is a sandy beach there, just be cognizant of the fact that there could be eggs under the surface of the sand. … Turtles lay their eggs starting in the middle of May until the middle of July, and the eggs can actually stay in the nest until the following spring. So those animals are there just under the surface.”

Identification: Adult turtles will have an olive-green to dark-brown upper shell that may be patterned with red lines. Their head, neck and tail are striped yellow. Their lower shell is red or orange and often has intricate patterns in black and yellow.

Legislation to protect endangered species

B.C. is one of the few provinces in Canada that does not have specific legislation to protect endangered species, yet has more species at risk than any other province. There are more than 1,900 endangered species inhabiting British Columbia, a province with one of the highest biodiversity rates in the country, yet there is only a patchwork of legislation to protect these species, including the Wildlife Act, which has been criticized by many as ineffective.

“There’s no significant species at risk legislation on the docket for the foreseeable future here in B.C.,” B.C. premier John Horgan told The Narwhal in 2019.

“A species at risk act has the potential to be considered an act of reconciliation by Indigenous peoples, if it is done with their input and guidance,” writes Steve Martin for The Times Colonist. “Following a model of free, prior and informed consent, endangered species legislation can offer more legal protection for Indigenous communities in a province of unceded territories.”

The federal Species At Risk Act (SARA) was created as a tool for Crown land, according to Switzer. However, this Act doesn’t operate the same as provincial legislation would, in that it can’t actually do anything to protect the critical habitats of species at risk. If we had provincial legislation that outlined how to manage areas where species at risk reside, that could improve bylaws on a municipal level as well.

Protecting these species for the generations to come

We won’t know what we lose until it’s gone. All species occupying an ecosystem together are intricately interconnected in a way that when one species is lost, we lose the relationship they built with another species in the ecosystem.

If you’re perhaps thinking, “It’s just another species of snail or frog; we have plenty, and it won’t hurt the ecosystem all that much to lose this one species,” Switzer would disagree with you.

“I think that each of these species came to be through all of these amazing processes over thousands of years, and to say they’re not needed or they’re no longer needed, it feels really ignorant to the process.”

Andrea Sadowski is working towards her BA in Global Development Studies, with a minor in anthropology and Mennonite studies. When she's not sitting in front of her computer, Andrea enjoys climbing mountains, sleeping outside, cooking delicious plant-based food, talking to animals, and dismantling the patriarchy.