By Michael Scoular (The Cascade) – Email

Date Posted: October 6, 2011

Print Edition: October 5, 2011

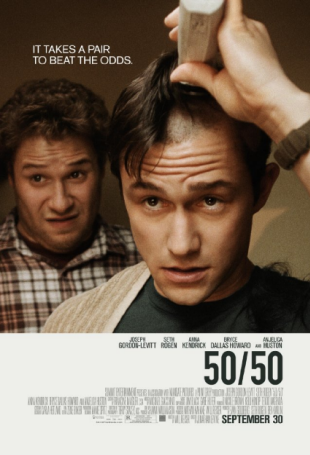

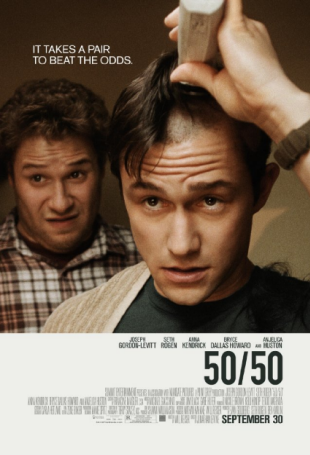

Crisis can reveal the real natures of other people: their hidden, truer selves. 50/50 uses the inciting attack of cancer as a genesis of plot, revealing what is beneath the calm and agitated exteriors of Adam (Joseph Gordon-Levitt) and Kyle (Seth Rogen). And what is underneath? Unfortunately nothing but a series of contrivances and shallow behavior that is less a tragicomic exploration of what happens to people in moments of accelerated mortality than an excuse for sexual antics with the seriousness of a cancer patient as its protagonist to fall back on, with the assumption that it validates the sophomoric ineptitude that pervades the movie.

Crisis can reveal the real natures of other people: their hidden, truer selves. 50/50 uses the inciting attack of cancer as a genesis of plot, revealing what is beneath the calm and agitated exteriors of Adam (Joseph Gordon-Levitt) and Kyle (Seth Rogen). And what is underneath? Unfortunately nothing but a series of contrivances and shallow behavior that is less a tragicomic exploration of what happens to people in moments of accelerated mortality than an excuse for sexual antics with the seriousness of a cancer patient as its protagonist to fall back on, with the assumption that it validates the sophomoric ineptitude that pervades the movie.

Adam is the one who discovers just how limited his time on earth is, and is placed as the protagonist, yet it is not he who is at the wheel of this movie. Perhaps not trusting Gordon-Levitt’s typecasted shy intelligence to sell the movie, Seth Rogen is situated at the front, his non-stop puerile non-humour dominating scenes. His incessant need to be noticed, even when it’s others that are more deserving of the spotlight, drives Adam to remark his distaste for his “friend” early and throughout the movie. And yet Rogen never goes away.

Far from his more affecting turn in the similarly-themed Funny People, Rogen here seems to be retreating back to his R-rated persona. His line readings have the feeling of a trademarked Rogen: an affectation of crassness. In a movie that is at least attempting to have drama along with its comedy, the broad excrement of the latter not only fails the picture but takes over whatever pathos Gordon-Levitt’s performance is trying to evoke. It’s another sad piece of evidence of the long arm of the Apatow.

And while Gordon-Levitt shows again that he is capable of playing the kind of morose, darkly humourous character he is here, more problematic is just what he is playing. A simple narrative question of what really changes with Adam reveals the superficiality of his journey abetted by disease. The key alteration to Adam’s situation is his relationship with his girlfriend, played by Bryce Dallas Howard. But as in an Apatow movie, female characters are lucky to be anything more than a sketch. Howard is ignored, underdeveloped, and, as a result, easy to kick down when the story calls for it. In a particularly revolting scene, a picture is waved around triumphantly by Rogen (minutes after an “excessive use of profanity” – his own euphemized description – towards the subject in question) repeatedly screaming and thieving the scene of whatever emotional effect it was supposed to have, whether amusing or melodramatic. And he’s taken completely seriously. No one responds to Rogen’s idiocy, his victorious find is all that is noticed. As Adam grows more disapproving of his carpool buddy, the sense that sooner or later the other shoe is going to drop becomes inevitable. And then an unforgivable, appalling character redemption occurs, that undercuts and ignores everything built up between the two main performers in the movie.

And this delving into relationship foolery is not isolated. The cancer ends up being a means to a “let’s get laid” series of party scenes and fortune cookie therapy sessions, rather than anything resembling real human experience. Though it may be based on writer Will Reiser’s encounter with cancer, the only thing feigning realism is the look of the film. This is a Hollywood version of cancer, where the only downsides are a few bags under the eyes, a shaved head, and one vomiting session, abbreviated of course. Surgeries are scheduled within the week and people are always there for each other, it’s only up to the patient to decide who gets pushed away. The camera and Gordon-Levitt try to emphasize that cancer, boy is it tough, with lines saying it’s tough and overhead shots emphasizing his separation, but cancer, excised from the title so as not to drive away audiences, is the farthest thing from the mind of the movie for most of its running time.

50/50 shies away from the ravages of cancer in favour of inconsequential sex pursuits and marijuana jokes. When Adam begins to give into hopelessness and anger, the movie is quick to act to dispel such thoughts with temptations of more relationship opportunities and a condescending pat explanation for how friends stay together. The title of 50/50 emphasizes the odds of whether Adam will survive, but the outcome hardly matters. The ubiquity of cancer makes it relatable, but 50/50 doesn’t want to explore much surrounding the condition, only exploit it for cheap laughs, the tepid, and the rote.