By Michael Scoular (The Cascade) – Email

Print Edition: June 19, 2013

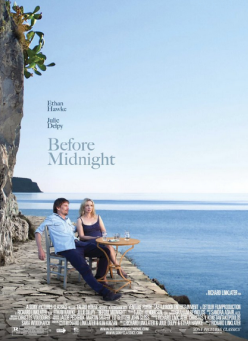

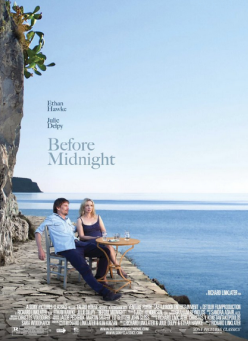

The Before films have no equal in recurring series, or for that matter anywhere else in film. There are other individual stories, novels, trilogies that may share some similarities, for a chronicle of a relationship can be found everywhere, but Richard Linklater’s collaboration with Julie Delpy and Ethan Hawke has nothing to do with most points of comparison within American romantic movies.

The Before films have no equal in recurring series, or for that matter anywhere else in film. There are other individual stories, novels, trilogies that may share some similarities, for a chronicle of a relationship can be found everywhere, but Richard Linklater’s collaboration with Julie Delpy and Ethan Hawke has nothing to do with most points of comparison within American romantic movies.

Revisiting characters and seeing the effects of time, both in the advancement of age and the invisible gaps left by the space between scenes, or in this case successive movies, does have precedent. The closest examples of charting people over time can be found in the films of François Truffaut with Antoine Doinel, the Up documentaries by Michael Apted, the way a career aligns in the case of someone like Emmanuelle Riva (Hiroshima mon amour to Amour), and there’s something to be said for the natural progression of any movie star as they age into older roles in the same genre. But unlike even the most ambitious of recent high profile American romance (This Is 40, The Five-Year Engagement), what is remarkable about Before Midnight is not how life finds its way into plots and stars and comedic expectations, but the way Linklater, Delpy and Hawke have created cinematic time that clears away all of that, laying bare the fine space between an act, a real conversation and a film.

That’s not to say this is an exercise or an unnatural experience. Before Sunrise contains in it the nervous energy of spontaneous romantic-conscious meeting, Before Sunset the mixture of sadness and joy that is reunion and Before Midnight, among many things, is also filled with the kind of humour possessed in a person rather than their comedy routine. Each movie, divided by years (from 1995 to 2004 to 2013), is essentially a document in semi-real time of time spent between Jessie (Ethan Hawke) and Celine (Julie Delpy). Their relationship evolves over a tendency to talk about everything that is important about being alive, but not in a way that is confined to speech, and not in a way that rests on canonized ideas. Development is matched in the movement of each film, in step with speech that has not become dated, even going back to Sunrise, because none of their conversations are about pop culture items each likes or the quotes of the moment that strike either as worth repeating. Jessie and Celine talk about what they are going to do (in work, love, their lives that they always rationally see passing through worst case scenarios), and then Linklater, through the continual revision of the time-structured series, shows it.

Unspliced conversations that unspool in walking and driving give a sense of intimacy to every character in a Linklater film, a staple from his earliest movies (Slacker, Dazed and Confused) to his more recent ones (A Scanner Darkly, Bernie), but it is also part of the larger effect Linklater’s focus has. Linklater doesn’t give his movies thickheaded political agendas – when they do come up, the most pointed statements will come from ambiguous characters, teachers, directions that encourage a measure of distance and interpretation.

In a landscape where “independent” has fractured into a genre of drama and comedy that has nothing of the term about it and the actual no-budget filmmakers that still fill that non-commercial avenue, Linklater occupies a third branch, which is independent in its way of looking at the world – there is an extension of kindness to the margins that shows in every casually great performance in a Linklater film, and also a sense of the feeling of improvised conversation, but ones so full they can only be something crafted and distilled. Linklater’s technique of long takes doesn’t sell but presents his teens, parents, and in between lives in a way that makes every glowing advertisement that plays before in a multiplex and every studio release supposedly in the same genre alongside it look hopelessly separate from the overflow of life Linklater excels in showing.

Before Midnight does not need extensive summary or quoting in this space – hearing the dialogue from the movie itself is the best way to learn about it, and if you’ve seen the first two in the series that’s context enough. It’s a movie that pulls back and examines experience but doesn’t fail to be one in itself, not living by vicarious romantic wishes but engaging with them in a way no other director is.

The social media-free walks of Before Sunrise and Sunset might look unreal in a way in retrospect, but Before Midnight shows that was never the point – the spaciousness of life is a problem that doesn’t change drastically for better or worse because of technology alone. A part of Before Midnight’s running time is taken up with the weight of schedules, the rarity of time free to be not “spent” or “wasted” but inhabited, and it’s part of the greatness of the series that Linklater extends the same question and its too-brief release in one gesture.