Print Edition: February 1, 2012

A tumbleweed blows by as two shadowed figures stand nearly nose to nose to iron out an agreement. A landscape of faces, marred by recent encounters, watching for the subtlest of movements that might give away their opponent. A final showdown builds to a climax, only to have the action pause for a detailed flashback to take place, wrapping up every possible loose end and putting a ludicrous spin on what traditionally would be time to build, not retrace. Memorably explosive silences are punctuation marks in an otherwise loud, catchy back wall of sound.

A tumbleweed blows by as two shadowed figures stand nearly nose to nose to iron out an agreement. A landscape of faces, marred by recent encounters, watching for the subtlest of movements that might give away their opponent. A final showdown builds to a climax, only to have the action pause for a detailed flashback to take place, wrapping up every possible loose end and putting a ludicrous spin on what traditionally would be time to build, not retrace. Memorably explosive silences are punctuation marks in an otherwise loud, catchy back wall of sound.

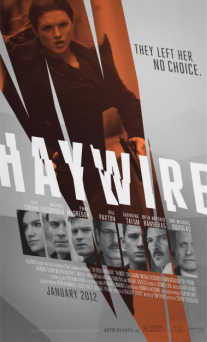

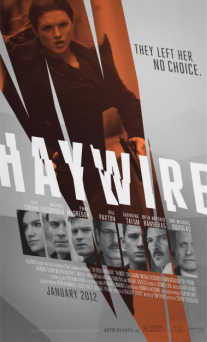

But this isn’t a Leone western. This is Haywire, Steven Soderbergh’s latest, an action picture starring Gina Carano as burned spy Mallory based on a script by Lem Dobbs that is so focused on figures, locations, and missions we don’t know of at the outset of the picture that a civilian whose car Mallory has borrowed’s (he’s along for the ride and she’s telling him what amounts to her life as a spy story, she isn’t one for awkward silences) dazed reply of “that makes sense” after being assaulted by a swirl of names is the most comical moment of the movie up to that point. But the plot, involving spy operations, possible conspiracies, and mostly takes place in flashback (the plot device of the civilian hearing her account is how we learn everything) can be boiled down to this: some people stand in Carano’s way. Dobbs’ script, though made up mostly of pared down dialogue for Carano and corporate speak that Michael Douglas makes sound admirably intelligent and Ewan McGregor turns into muddled malarkey (the most outrageous of Haywire’s spoken plotpoints is how Mallory could possibly have been in a relationship with him for six months), is far from outstanding work, relying too heavily on structural tricks and a mixture of genre familiarities to be terribly interesting on its own, but Haywire’s strength lies solely in its action, which speaks so much louder than its words.

Gina Carano faces off with a similar style throughout the movie, but due to the improvisational appearance of the combat which is heightened by Steven Soderbergh’s decision to capture all the action with a steady camera, each encounter is distinctly varied. Soderbergh has chosen not to jerk around the frame to create the appearance of intensity – the force of the kicks, strangleholds, shaking walls and threatening to snap both bedframes and necks is all the intensity the scenes need. The way bodies are beaten and falls are aggravated recalls tales of stunt person injuries on the sets of Tony Jaa movies, yet here there’s the presence of the actual actors in the main roles doing the fight scenes. Carano—who, in addition to her athletic skill, has a face the camera loves—uses every eye shift to tell a story and convey experience. Her recognizable presence imparts information the script can’t; so, too, is this the case for Michael Fassbender and Channing Tatum. However, in the case of Ewan McGregor this works in the other direction, as to how he ever got approval for field duty is questionable given the performance we see. But maybe that’s intentional.

In every case though, David Holmes’ score—not quite a Morricone whistle, but every bit as invigorating as it sings the rhythms of espionage in a way Michael Giacchino only wishes he could—moves scenes beyond their natural velocity, dropping out only for the ritual of fighting and the dead spaces of the corporate building. Soderbergh’s digital aesthetic is easily recognizable by now, and the way the queasy yellows of artificial light indicate undesirable territory is as unsubtle as his color coding in Traffic, but an interesting way of playing with the lighting and sounds Soderbergh’s penchant for sorta-realism creates.

For 90 minutes, Haywire towers above similar stories because of Soderbergh’s carefully framed images, every shot packed with information, every punch landing with a wince. There’s a scene early on that opens with post-it notes laying out every objective and every step of the plan that the Mallory-led team is about to execute and includes such helpful descriptions as “BAD GUY #1.” Its actual execution is a mixture of surveillance footage crosscut with Mallory’s team expertly doing their job and Channing Tatum waiting in a car all overlaid with Holmes’ spirited, playful score. It’s a scene that’s been done 100 times elevated by Soderbergh’s strengths as a visual artist and collaborator.