By Michael Scoular (The Cascade) – Email

Print Edition: July 3, 2013

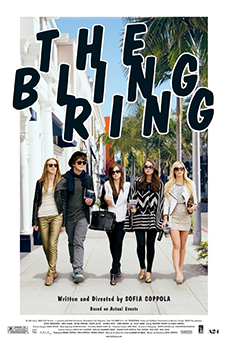

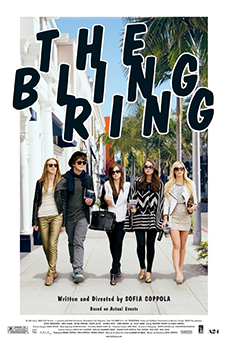

Marc (Israel Broussard) arrives on his first day of lower-rung school, self-conscious and wishing unconsciousness, until he’s spoken to by Becca (Katie Chang). Invited to the beach, to parties, to the group he invisibly becomes a part of, Marc is taken to. He’s able to comment on the fashion worth flipping past, pausing and flipping back to in a magazine, open to the idea of post-nightfall possession taking that gives the group its eventual notoriety. Director Sofia Coppola working with editor Sarah Flack skips past backstory, presenting The Bling Ring as initiation before a series of robberies in linear, reconstructive detail, emerging as repetitive. Sliding doors, arrays of labels and hasty bag snatching elicit opposite responses by their majority presence: the glee of excess, blurting out and breathless, and the boredom of banal attraction and material gain, any narrative undercut by the film’s true story ending-as-prologue, and any transcendence of partaker and surveillance roles made nearly impossible by Coppola’s arrangement of facts and their accessories. Marc as a “way in” in the tradition of blank new kid roped into a new stream of living is a fakeout, for after brief intro and a final subjective line over slow motion, he turns out to be a model to be observed like all the rest.

Marc (Israel Broussard) arrives on his first day of lower-rung school, self-conscious and wishing unconsciousness, until he’s spoken to by Becca (Katie Chang). Invited to the beach, to parties, to the group he invisibly becomes a part of, Marc is taken to. He’s able to comment on the fashion worth flipping past, pausing and flipping back to in a magazine, open to the idea of post-nightfall possession taking that gives the group its eventual notoriety. Director Sofia Coppola working with editor Sarah Flack skips past backstory, presenting The Bling Ring as initiation before a series of robberies in linear, reconstructive detail, emerging as repetitive. Sliding doors, arrays of labels and hasty bag snatching elicit opposite responses by their majority presence: the glee of excess, blurting out and breathless, and the boredom of banal attraction and material gain, any narrative undercut by the film’s true story ending-as-prologue, and any transcendence of partaker and surveillance roles made nearly impossible by Coppola’s arrangement of facts and their accessories. Marc as a “way in” in the tradition of blank new kid roped into a new stream of living is a fakeout, for after brief intro and a final subjective line over slow motion, he turns out to be a model to be observed like all the rest.

Harris Savides, in his final film as cinematographer before he passed away last year, has his work fractured. Unlike the beautiful watermarks of his past (The Yards, Paranoid Park), The Bling Ring is split into stark, static designer homes, designer casements, and clubs where young minds dream of getting their hands into designer lives, the digital imperfection of surveillance footage and webcams, and television magnification and recreation of celebrity interviews. The last item is The Bling Ring at its seemingly overdetermined and obvious worst. Coppola flashes through red carpet barrages of celebrities away from their being-thieved mansions and intersperses a small handful of interviews with the accused, mimicking journalistic questions, some of them pulled from the Vanity Fair contributor that formed the basis for Coppola’s script. One yields a state-of-affairs statement from Marc, who speaks of how this one story “[shows] America still has this sick fascination with a kinda Bonnie and Clyde type of thing.” Taken at face value or its easiest interpretation, there aren’t many ways to go from here, but Coppola hasn’t made a movie that supports the comment’s moralizing backtracking.

The Bling Ring never entertains questions about the legality of or a final purpose to the spur-of-the-moment raiding – it isn’t the lines already drawn by prosecutors or commentators Coppola is interested in. What Coppola has shown an affinity for, and continues to do with The Bling Ring, is infiltrate a supposedly hermetic existence – in this case the pop culture doused teenage nothings who have no qualms with being attracted to the images that line supermarket checkout lines and internet gossip zones. Part of the suggestive portrayal Coppola enters into is that these aren’t that different from the youth of any generation – every kid has something to hide under their bed, some false reason they were out with friends, and a skill at creating a performance to show their parents and anyone else not worth sharing with. But Coppola taps into the currency that drives this particular one so exactly it blurs into conversations, resembling others (Spring Breakers, Fitzgerald, the type of cultural appropriation of cool in something like Miley Cyrus’ reinvention) while retaining a small piece of itself. Coppola sticks with unmoving shots that observe every inch of space these kids inhabit, creating new, strange tableaus of stop-start selfies, webcam half-silent singing, and awkward posing around adults.

If there are any tells that this isn’t an entirely tragedy-framing, sympathizing version of the story, it’s in that last relation – where parents are completely ancillary, showing up to be near-comedically fooled and then only once or twice. The performances, Emma Watson’s in particular, about to launch into tales, smoker’s eyerolls, and indirect address, are played as if they are always lying to their parents, even around when they’re hanging out – that mix of you must be dumb condescension and undisturbed termination of feeling. Coppola is dealing with models and masks and the incomprehensible mind of a group seemingly on autopilot, to its own mind in a blur of easy gratification to the exclusion of anything else.

Coppola keeps returning to favoured stylistic markers – the perfect synchonicism of pop songs and pop images and the abstract staging of a robbery in slow zoom, and there is a contained glee in the colors and fabrics and sheen of “new” materials. But The Bling Ring resounds less with the sounds of Marie Antoinette, continuing more from her alienated Somewhere, where decadence held no comfort. There’s some pity in the distance that the camera holds its subjects in, methodically repeating the same action, expecting a new, changed result. Marc distances from himself, saying America has a fascination with anti-heroes, as if he isn’t the same. But it isn’t as separate and closed as that. In the group’s “Visitez mon site” final punchline and Frank Ocean coda, there’s an indescribable pull that’s baffling and obscure – possessing some measure of self-knowledge, getting lost in someone else’s story and grasping after their own.