Print Edition: September 4, 2013

Fred Astaire famously demanded that all his dance numbers be shot in a single take at a distance that allowed for his entire body to be visible within the frame, a cinematic idea of purity and truth – it could not cheat, and it showed everything brilliantly. The fight scenes in Wong Kar-wai’s The Grandmaster might as well be dance scenes, more footwork and deflection than broken bones, but this becomes noticeable only over time. Wong’s picture of a transitionary period is broken into pieces, and his aesthetic has always been one of staggered rhythms, framerates, and overmatched, smeared colours. There is still a truth to what Wong shows, but it never settles easily, and never shows everything.

Fred Astaire famously demanded that all his dance numbers be shot in a single take at a distance that allowed for his entire body to be visible within the frame, a cinematic idea of purity and truth – it could not cheat, and it showed everything brilliantly. The fight scenes in Wong Kar-wai’s The Grandmaster might as well be dance scenes, more footwork and deflection than broken bones, but this becomes noticeable only over time. Wong’s picture of a transitionary period is broken into pieces, and his aesthetic has always been one of staggered rhythms, framerates, and overmatched, smeared colours. There is still a truth to what Wong shows, but it never settles easily, and never shows everything.

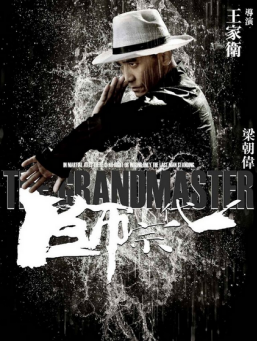

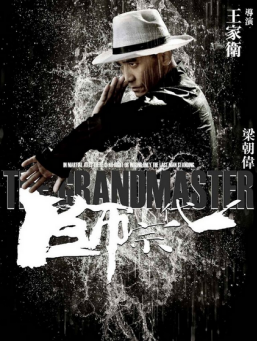

The Grandmaster begins through a disorienting slow build, showing an initial meeting and challenge between the divided sides of Chinese martial arts (the North and the South), before zooming backward through the stages of learning and observance of various styles by Wing Chun practitioner Ye Wen (Tony Leung). Wong does this without differentiating between timeframes—the past and further past look the same—or leaving much room for the audience to catch up to the weight of history – significant and insignificant moments pass in word and action with a similar sense of ritual and gravity.

Some of this is due to the alterations made to Wong’s film for North American release, but most of the images between the different versions of The Grandmaster are the same: blurs of motion become immediate effects on architecture, a brief stop of held breath and words loaded with poetic density, before the likelihood of an eruption of combat becomes a certainty again. For most of the first two thirds of The Grandmaster, hardly five minutes seem to go by between fights, and characters do not have dialogue but sayings plucked from things ancestors and legends said, used as a common tongue between former and eventual combatants. This stop-start, everything-magnified nature threatens to exhaust if taken as the hero’s journey narrative the North American cut wants the movie to be, but is more palatable when the desire to know everything about each event and decision is let go in favour of the series of short stories Wong’s fractured tale comes across as, each ending in a snapshot of faded photographic tableau.

Contradicting the saying that suggests those who dwell on the past are unhappiest and their best selves are the ones that look to the future, in a Wong Kar-wai film every timeframe resonates with longing covered in bitterness, briefly touched by romanticism. While The Grandmaster isn’t part of the genre, it carries some of the obsessions of the noir mentality: Wong often composes for shadowy faces pushed to the edge of the frame, and weary characters regard their inescapable histories and complicated ones in the making with near-sardonic lack of surprise when not pushed around by tragedy.

The historical angle is emphasized in The Grandmaster to a greater extent than anywhere else in Wong’s films, but the effect isn’t an imposition of fact-based narrative. Wong’s shaping of mood, spilling into the air even as action choreography takes over, does away with ideas of linear progression over time, instead the development of kung fu and master-apprentice relations is a messy conflict of generational translation beyond its rules and customs, even as the film seems to exist largely within these confines.

Watching The Grandmaster in its current form is unfortunately not ideal, as between the fact its North American distributor had the film re-cut and that the internet exists, along with similar news from recent Chinese epics (Red Cliff) and upcoming Asian-directed action (Snowpiercer), the knowledge that this is not the way the film was originally meant to be seen is unavoidable. There is something to be said for The Grandmaster’s North American cut still being a version of the film, a unique take on the same, larger story. But that the bulk of the cuts are to the dramatic weavings of the story is plainly evident, contributing to the wall-of-action opening, but also taking away from a staple of Wong’s films: multiple narrators contributing to a tapestry of personal histories. This only shows up briefly near the end of the North American cut, in a scene involving Gong Er (Zhang Ziyi) – startling in its appearance because of how her perspective has been denied for most of the movie’s course, suggesting another entire length of the film, one without deadened idiosyncracies and insulting concessions to viewers unable to watch but apparently willing to read.

Instead of Wong’s full development, the film’s characters are introduced with an English-language credit, stating their names and titles and often unnecessarily repeating information evident from just listening to dialogue. Numerous, ad copy-lite historical intertitles take Wong’s film for a slavish biopic, one that sets up a connection to Bruce Lee as if it is a prequel, when in actuality nothing in the film’s images suggests anything so strong – it’s all culled from the hope of brand recognition as a selling point, and repeatedly distracts from what should be a greater film.

Taken together, it’s enough to make swearing off what sounds like a compromise sound like the best way to go, but if anything good can come of this, there is the hope the comparison of the two versions will only reveal the centre of Wong Kar-wai’s cinema further—the Chinese cut is widely available already due to the delay of work on the North American edit—as a work of restoration, but also of breaking down.