Print Edition: February 8, 2012

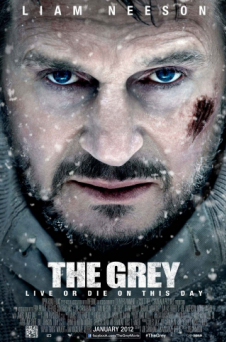

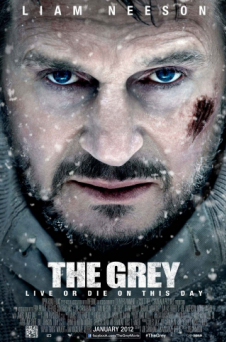

The Grey, Joe Carnahan’s second consecutive collaboration with Liam Neeson as a lead, again pulls strength from Neeson’s size and charisma, which were two of several well-tuned components that made The A-Team a far better movie than its TV-adaptation reputation might suggest. In The Grey, they again work together, conveying the expansive intensity of a movie’s world, as well as lending a certain degree of familiarity and likeability to the lead role, but Carnahan is working in a different register this time.

The Grey, Joe Carnahan’s second consecutive collaboration with Liam Neeson as a lead, again pulls strength from Neeson’s size and charisma, which were two of several well-tuned components that made The A-Team a far better movie than its TV-adaptation reputation might suggest. In The Grey, they again work together, conveying the expansive intensity of a movie’s world, as well as lending a certain degree of familiarity and likeability to the lead role, but Carnahan is working in a different register this time.

Neeson, a thin line of darkness against the white wasteland he’s lost in, has a lot to contend with. Some might wonder what the significance of the unassuming title is, and like a lot of things in the wilderness, it isn’t something that can be completely pinned down, but besides the obvious monochromatic palette of the northern British Columbian winter Carnahan captures with a long, steady gaze (an abrupt change from his Tony Scott-related action aesthetic) and the beloved “grey area” of what is the right thing to do in sticky situations (one of the few survivors of the crash that lands the cast in the middle of nowhere shouts at one of the predatory elements of their dangerous trek to somewhere “You’re not the animals, we’re the animals!”) there is Neeson himself, caught in limbo before he ever arrives in the land where both the sky above and the mud below are covered in suffocating white.

Neeson’s world-weary, poetry of an opening is followed by a reveal that his character Ottway’s primary memory of childhood and the source of his haggard inspiration is poetry. All plays out to a long take backdrop of bar fights and curses, which give way to more curses, only in response to blood and death rather than aching backs and spilled drinks. Despite their exteriors, where the main way of determining who’s who is the length and cut of their facial hair and the lines on their faces, the supporting cast of The Grey regards a fellow man’s passing, inevitable though it apparently is, with the terrified gaze of someone seeing their first grandparent slip away. And Neeson stands beside them all, the same yet different. He acclimates to the terrain and the habitat though he’s never been there before, and is in constant search for something he’s never seen before. Next to the way he carries himself, the tremulous, then supposedly tough “fuck”s and “Jesus Christ”s of his fellow passengers sound like the most empty statements in the world. “I just want to get laid one more time,” one bruised body says, but Ottway has other things on his mind. He returns, again and again, to a memory of his wife; a memory that, though it takes place under sheets, is distinctly asexual. It’s a light in his memory, a moment he can touch but not feel anymore, and as clichéd as the flashback fragment might be, it’s a more enduring image than one expects in a movie where men laugh wildly following the lustful joke-that’s-not-really-a-joke above. In between the whites of the deathly soft crunch of the snow and the dead soft touch of his wife, Ottway laments at the sky, “I wish I could believe in that stuff.” Though there might be moments of grace in The Grey’s landscape of indifference, there is no heaven.

Most prominent of their physical struggles is the threat of death by wolves on the hunt. Though the fear of being preyed upon with no help on the way reaches for plausibility, these predators are a movie manifestation. The pack of supposed hunters is notable not for their realistic behavior (they appear only when one is alone and all is silent, or emerge as a front line of menace in perfect unison) or the way in which they are dispatched (more often than not they slink away because man make fire), but for their appearance, both tangible and not. They appear with demonic glowing eyes, then pass away like mist, triggering nightmares for men who act more like boys in their presence. And how can they not? For them, they are the perfect representation of ghosts, urging them across the expanses of a dream world where the snow never ends, and the pain never ceases.

The Grey features some stumbles along the way, including a “third-act moment” that is all-too-familiar territory for a movie that’s supposed to be about the opposite, but the images (veering between eerily coherent and complete cacophony) and the oppressive sound (there is a score that doesn’t disrupt the mood, but it’s the wind, all piercing whistles and thundering gusts, that permeates as a more than adequate soundtrack) all tie together in the mind and body of Liam Neeson and feature most strongly.