By Michael Scoular (The Cascade) – Email

Print Edition: January 30, 2013

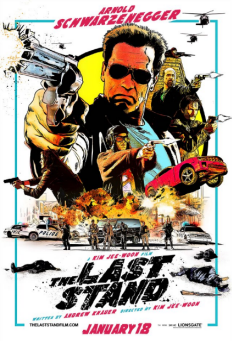

This is a story that has happened before, and will continue to repeat as long, it seems, as there are borders, gaps that only temporarily intersect, and individuals and collectives that do/do not want them crossed. Physical, geographic, prejudicial, generic borders, broken by travel, assimilation, violence. The Last Stand is not a serious movie, but it comes from the somewhat serious (maybe better described as curious) tradition of talented Asian auteurs gaining attention, coming to America, making a movie (which tends to be restricted by new rules and divergent opinions), and very rarely finding the same elemental collaboration leading to the type of work that made them worth seeking out in the first place.

This is a story that has happened before, and will continue to repeat as long, it seems, as there are borders, gaps that only temporarily intersect, and individuals and collectives that do/do not want them crossed. Physical, geographic, prejudicial, generic borders, broken by travel, assimilation, violence. The Last Stand is not a serious movie, but it comes from the somewhat serious (maybe better described as curious) tradition of talented Asian auteurs gaining attention, coming to America, making a movie (which tends to be restricted by new rules and divergent opinions), and very rarely finding the same elemental collaboration leading to the type of work that made them worth seeking out in the first place.

The Last Stand isn’t entirely devoid of Kim Jee-Woon’s penchant for a little bit of comedy, a bit of discussion of the morality of death, and a lot of blood, but the mixture is off, the backwards—modern, yet archaic—structure of present-day American action feeding into what comes out as much as Kim’s sleight-of-hand and ability to twist excess into ambiguity.

The majority of attention given to The Last Stand has to do with Arnold Schwarzenegger being in the lead role, but from the start he’s reduced by the inconsistencies of written structure. One of the possible reasons for directors coming to a new country, a new system, and not having the same kind of success comes from directing scripts not only not theirs but lacking their sensibility – while The Last Stand features enough in the Arnold segments to count in Kim’s favour (a should-be peaceful weekend, a sheriff tired of corrupted city life, now anchored in a one-street outpost), it’s quickly made incidental by a lengthy Las Vegas sequence—generic police escapee frustration starring Forest Whitaker—that feels like it has no business being in the same film. The closest comparison in Kim’s previous work would be The Good, the Bad, the Weird, and like that one, The Last Stand works as a riff on a classic western, in this case High Noon – but High Noon didn’t take an hour and change to finally be High Noon, and neither did it feature pages and pages of miscommunicated dialogue – while the powerlessness of watching on monitors and speaking digitally from a distance places The Last Stand firmly as a movie of the present, it is at odds with the spirit of Kim’s light grandiosity, which hardly gets a chance to come out. The two plot threads are unconvincingly crosscut, with one progressing toward the other through the medium of single-vehicle “action” scenes that resemble nothing more than a recurring Chevrolet advertisement.

What’s missing is that Kim’s ability to translate the balletic freedom of physical combat to mechanical action is grounded, conventionalized – no extended, repeated, CG stitched-together long takes and whip pans here, just competence. The size of artillery is the draw, rather than the way it can be used unconventionally. After the landscape of iconography of G/B/W, The Last Stand might be called an advancement, a venturing into a real setting rather than a borrowed one, but what strikes is the sense of how scenes and ideas are not taken to their fullest exploration – save the opposite-end-of-the-street showdown, much of this is perfunctory or left hanging.

Kim Jee-Woon’s daylight clarity means The Last Stand never sinks into anonymity, but at the same time there is so much here that is nothing new – of course it’s the single female member of the police force that proves unreliable, of course the makeup of criminals (Mexicans) will never stand up to the good Americans protecting their town, of course the movie will end in repetition, beating, something called heroism. There’s nothing Kim and cinematographer Kim Ji-Yong can do to transform the final fight—wrestling moves and stab wounds—into something terribly interesting visually, but in its monotony, the scene gains a feeling of displacement. The significance of setting (a bridge between countries, a bridge easily constructed, a bridge where the toll is desired to be an attainment of virtue through blood squibs and persistence) takes over, and Arnold’s payback line raises the status of personal identification – the location of a spirit of a home. The Last Stand can’t be regarded as the highest point in Kim’s filmography, and it has problems with the way it grows and the way it hangs onto genre limitations, but there are enough hints at greatness within—the need for reconsideration as more than something to be disposed once consumed—to suggest that whatever direction Kim goes in from here, this re-starting point has not been fully compromised.