Print Edition: January 9, 2013

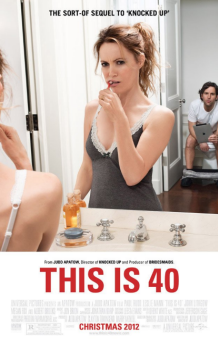

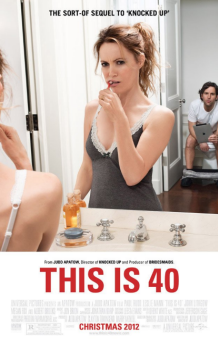

There are countless things done in the name of getting out from under, struggling against, freezing the advance of, hiding the effects of, entropy. Judd Apatow, for all his creative influence over the entire genre, it seems, of American comedies, in his own films, has developed an intense preoccupation with this most unfunny subject – a focus on age and malaise and unhappiness. Autobiography could be said to find its way into any creative work, however small, but Apatow pushes this to the forefront as well, making the fact that Leslie Mann, Maude and Iris Apatow are both a form of creative inspiration and a creative rearrangement of family for the screen (for the inspiration) unignorable. Apatow’s, then, is currently a deeply personal, physically-fixated cinema – but one still tethered to the comedy that is his calling card, the affluence that is a result of this, and a conservative bend that presents itself as he goes deeper into personal responsibility and its contradictions, and in the way he resolves, or doesn’t, the anxieties and criticisms he himself proposes.

There are countless things done in the name of getting out from under, struggling against, freezing the advance of, hiding the effects of, entropy. Judd Apatow, for all his creative influence over the entire genre, it seems, of American comedies, in his own films, has developed an intense preoccupation with this most unfunny subject – a focus on age and malaise and unhappiness. Autobiography could be said to find its way into any creative work, however small, but Apatow pushes this to the forefront as well, making the fact that Leslie Mann, Maude and Iris Apatow are both a form of creative inspiration and a creative rearrangement of family for the screen (for the inspiration) unignorable. Apatow’s, then, is currently a deeply personal, physically-fixated cinema – but one still tethered to the comedy that is his calling card, the affluence that is a result of this, and a conservative bend that presents itself as he goes deeper into personal responsibility and its contradictions, and in the way he resolves, or doesn’t, the anxieties and criticisms he himself proposes.

This Is 40 is at least a step forward from Apatow’s previous, Funny People – the business of comedy, an insider self-pity party traded for the business of life, a perspective of growing facets, if still limited to a single house, and still focused on the dissatisfaction of people (Leslie Mann, Paul Rudd) that have “made it” in that they are the managers of their own lives. The fact Apatow refuses to step outside the sphere of upper-middle class privilege (the horror is that the family might have to move into a smaller house, that Rudd might not get the full value of a Lennon artwork in online auction, etc) might hamper any kind of attempt at calling this anything but self-indulgent, but by detailing every aspect of his familiar surroundings, Apatow does get at a number of things that make a simple dismissal on those grounds work only if most of the film is ignored. This Is 40 is Apatow’s most diffuse film yet, hardly caring about plot, existing more as a series of anecdotes, arguments, and structured only by a birthday party as its beginning and end. Though this dating means the movie takes place over a strict set of weeks, this is hardly noticeable, as, while Apatow’s movies have always carried a dead-air improvisational quality, lacking form but hanging around long enough to eventually find something to laugh about, this quality, even more than in Funny People, is applied not to plot but detail, not to jokes but drama. But in a sense this works, as This Is 40, aside from its cameos and broader parts for smaller characters (Megan Fox, Jason Segel), is a comedy where the laughs come from apperception, the ability to see aggravating experience turned into a mixture of reconsideration and ridiculous, foolish strife, found in the way scenes fall apart, end too quickly, grow longer than comfortable.

Though Apatow’s movies and their imitators have regularly revolved around how men can assert themselves, This Is 40 is a movie where this idea is constantly undermined. Where Rudd’s character attempts to stay in a routine, failing to react and adjust and make amends, Mann’s rejects complacency, building not towards financial or cultural capital—as Rudd puts stock in (and fails in growing)—but a personal improvement, though the feasibility of even this is called into question. Some of the comedy of recognition of This Is 40 is in the characters themselves – they are self-aware, and call each other out, and at one point make a list of resolutions. But no matter the reminder of “choose to be happy,” words can’t cut through masks – Apatow’s listing of Cassavettes as an influence on this film is tenuous at the best of times, but it’s possible that through an unintention, by simply reimposing a kind of reality of situation, the natural fronts and breaks that defined Cassavettes’ emotional realism comes through in places. Apatow does two things that stand out: he shows these characters at their lying, childish, hateful, self-centred worst, and then asks for acceptance all the same. Within the film, Rudd and Mann throw off lines like “it’s not our fault” and “it’s them not us” – a willful blindness as a way to momentary peace, exclusion as way to election, while outside, we are able to see through their statements, comparing them to what’s been done before. For some incompatibility remains – Mann in the middle of one argument delivers a line that suggests she was, and could have been, fine on her own, and the question (here, and throughout) is how much of this is an argument strategy, and how true a representation it is. In the variety of relations This Is 40 displays (work, home, friends, strangers) there is the appearance of different appearances for different people – then which is the best, or true, or internally consistent person underneath, and is that the one the film ends on? This is not necessarily what Apatow intends to show, but this is, if anything, a carefully observed movie, and what comes out of that is more than what is said.

The most noticeable organizing principle, imbalanced division of This Is 40 is its music. Setting up a split between fun but foolish music and real, lived-in artistry, Mann and Rudd sit on either side of the poptimist/rockist argument, with neither side seemingly willing to even try to listen to the other. Apatow, strangely enough, doesn’t even try to hide the side he takes, as aside from a single scene in a club, the soundtrack of This Is 40 is entirely made up of acoustic, “authentic” songs that, as Mann’s character says, “don’t make people happy,” and according to Rudd’s, are “art that will stand the test of time.” It might seem inconsistent, or an act of giving in, that Mann at the end of the movie, says she likes the song, played sitting down with acoustic guitar and stool, her husband has brought her to. But, like the rest of Mann’s performance, there is a resistance to any neatness in the script (and the rhyming towards the end does deserve that word), an assertiveness Apatow and his male lead lacks, that, like the idea behind pop utopianism, does not exclude, but searches for affirmation in the most unlikeliest of categories. In this separation, there is perhaps the reality of the distance between people, but with that comes the reality of connection – it’s unideal, unalterable, but better, in its own, imperfect, post-romantic way.