Print Edition: October 3, 2012

This is the first of three weeks of coverage of the Vancouver International Film Festival (VIFF). With no full film studies program at UFV, there is no better place and time than VIFF’s sixteen days to learn, even if in a small way, of filmmaking in the present in its multifarious forms.

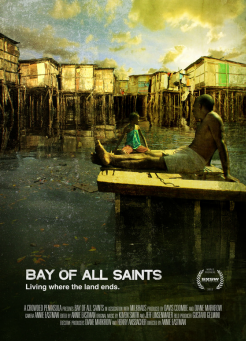

Bay of All Saints (USA/Brazil)

Bay of All Saints covers a period of seven years, yet doesn’t cross 90 minutes. It attempts to encapsulate a country’s neglect of its people, yet remains tied to a very small part of it. It follows real people, yet many of its situational conversations seem arranged. None of this is to its discredit, as Bay of All Saints, the first directorial work of Annie Eastman, unlike many issue or poverty documentaries, has a contra for most of its sentiments, political action, claims to easy truth.

The place is Brazil’s palafitas, no-income housing on stilts over a manufactured delta of trash, and the throughline is refrigerator repairman Norato. Eschewing verite by shakiness, the film dials into its four main subjects mostly in traditionally shot-reverse shot, mic’d interviews by Norato, replacing the voice and direction of the filmmaker with the subject. This is a microscopic-by-distanced picture of a system that has led to class segregation, one that shows up most unavoidably in the oblivious sheen of a TV-star turned politician briefly visiting who “knows” their plight, and a teacher reciting poetry, descriptive but at a great remove from the experience of one of her students.

Through observation and following through the palafitas, what come out are people that have grown used to the ignorance of the government, accepting, for a time, their closed-off environment of decay. A gesture at a plan for a solution of state housing is the feint that sets off the central turmoil of the documentary, but they can see nothing of the political process, are excluded from it. Nothing good, nothing resolved can come of this, and Bay of All Saints, commenting through its editing, its not commenting, leaves everything hanging.

Student (Kazakhstan)

[In the final paragraph of this review, the ending of the film is discussed.]

The question of re-appropriation – if it is simply copying, can ever be considered at equal or more than its ancestry – is present at all times in Derezhan Omirbayev’s Student, a work inspired by the framework of Fyodor Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment. Where in early works like Kaïrat the mark of great filmmakers, the primary one being Robert Bresson, could be suggested, in Student, it is obvious. Unmoving shots capturing movement or just as likely its absence, spatial violations and redefinitions through editing, there is no mistaking how closely Bresson’s conditions of visual creation are followed. There is some deviation within these lines, yet two of the most sticking scenes in Student are its most explicit references: the first act of violence in the film in its suprisingly-set opening, and the first dream, mixing memory (of another time, other films) and reality. Elision by incorporation is where most of Student finds its form.

A pointed, early series of shots during the film’s opening credits is of the architecture of the Kazakhstan glimpsed by its bus-travelling protagonist, steel and glass towers you might find in every major city in the world. Following this, whether by lecture or television, the two primary ways information is delivered during the film, the condition of Kazakhstan and how it is being reshaped by outside knowledge and losing its regionality, is up for comment. American images show up as kitsch or televisual signs of death, and the murder weapon is not a tool but an automatic killer, as distanced and easy as the lecture hall discussion of capitalism. It is in that setting other ideas of great force are introduced, with equal deference given to that earlier topic and to the writings of Sun Tzu and a local saying. How a student interprets all this is the narration of the film, as Omirbayev leaves aside the crime and punishment of plot as much as possible.

As a closure to all the watching of foreign dynamics, Omirbayev saves his most explicit visual quote of Bresson’s Crime and Punishment reworking, Pickpocket, for his penultimate shot, making what follows even more noticeable for existing. The child, listening, watching, the beneficiary or otherwise of the influences incorporated and carried, previously in the role of the suicidal Svidrigailov, now addressing the camera, studying her student teachers.

Reconversão (Portugal)

It’s likely that for someone already possessing a deeper understanding of architectural design and photography, Thom Andersen’s film essays aren’t so revolutionary, but as someone who brings neither to viewings of this or Andersen’s previous, sprawling Los Angeles Plays Itself, that is exactly what watching them is like.

Andersen proposes an image, in the more well-known first case a film clip, in Reconversão’s, a few frames of Eduardo Souto Moura’s designs, standing, ruined, in between, and explains them first in terms of their observable qualities, then what they represent. These few frames, taken by Peter Bo Rappmund, are projected at a speed that is fragmented, and yet encapsulates a greater part of an ungraspable whole, showing Souto’s buildings over time, than if they were shown at a normal framerate for film. Andersen’s narration, voiced again by Encke King, measured and uninflected yet awakening in its atypical calmness and dry wit, takes this display of natural granite and manufactured steel in the form of houses, public buildings, and unbuilt structures, and doesn’t authoritatively demonstrate, but opens up these objects to interpretation, both physically and philosophically.

As in Los Angeles Plays Itself, much of the construction of Andersen’s piece is of quotes, though here it is of words instead of images. Souto Moura’s own rationale for what his methods, materials, and views on the lifespan of a building as a part of life make up a large part of the discourse, but this is balanced by Andersen’s own knowledge of ways of seeing. Their combined observations comment on the buildings on the screen, documenting lifespans of ideas and development of design, but what Andersen through Souto Moura is saying about the spaces humans live in, apply also to city planning, artistic expression, and the nature of relationship between human beings and their environment in a wider, applicable way.

If Reconversão doesn’t necessarily add another layer to what his large theses were in Los Angeles Plays Itself, it is still a clarifying, demonstrative approach to an underrepresented perspective in film. Every shot, every movement in every film/life is a reaction to the space or openness that surrounds it, and understanding this, as gleaned from Andersen’s work, is an opening into something intelligently spectacular.

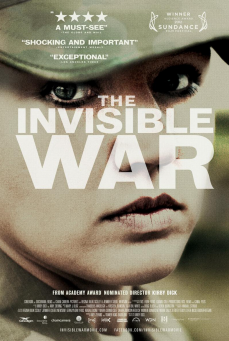

The Invisible War (USA)

The most sickening thing about The Invisible War is its consistency. At one point in his documentary on rape and related physical abuse in the United States military, Kirby Dick cuts through as many as 20 stories of violation, all remarkably similar, all going through the same steps, all lives ruined, right through to the conclusion: that nothing was done about it. Chain of command, personal (male of course) relationships, protection of personal and symbolic military reputation, all conspire to see an obscene number of women raped, disavowed and abandoned by the institution they joined up with. Statistics, interviews with those on the critical and bureaucratic sides of the (to this point) mostly silent argument, all add up to a single story of self-sustaining rape culture, violence and cowardice.

Dick has made it a practice to take on institutional sins of omission and hypocrisy, and in terms of approach, The Invisible War most resembles his closest previous documentary Outrage. But no matter the ugliness of the subject matter or the built-in emotion of its title, that documentary’s mixture of news footage and blogger interviews had a very short way to go if met by ideological opposition, possible to be dismissed by those unconvinced as either partisan or relying on hearsay rather than facts. Here there is no room for argument. Sometimes a documentarian will say that their issue divulgement is there to start a conversation, but what comes out of the copious interviews here is how meaningless talk is. The military personnel responsible hide behind words, none of the talk on the part of those abused can completely repair the destruction already done, and all of this has been recycled over more than half a century. It is the culture, the people, that must change – this is unacceptable even as discussion.

But these interviews, conducted by Dick and producer Amy Ziering and assembled by editors Douglas Bush and Derek Boonstra are a necessary, single step, and The Invisible War, one hopes, is the kind of documentary that becomes a moment in the past where something began. In the middle of a meeting between survivors at one point in the documentary, it is brought up, with regret, that “knowing that there are others who have gone through the same thing,” to not be alone, is a comfort. It is, as something to be discovered, and also by its very existence, the horrifying undergirding of this documentary.

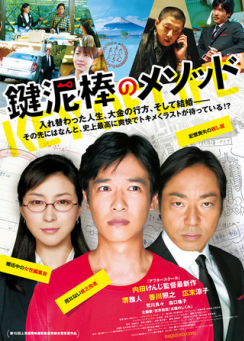

Key of Life (Japan)

Key of Life introduces, then quickly flips and exposes its actors as actors, acting roles as defined by the narrative, but also invoking the acting that is unreal, exaggerated, and being played out transparently for the screen. But this illusion of acting has its appeal, as in the movie’s stars: Masato Sakai, Ryoko Hirosue, and Teruyuki Kagawa, best known in North America for Sukiyaki Western Django, Departures, and Tokyo Sonata, respectively, but not limited to just that in Japan. Taking amusing advantage of this comfort, writer-director Kenji Uchida is able to flip between non-serious gangster-lifeswap plot and extra-filmic actor wheeling, assuming multiple roles as a genre confined/liberated comedy. Assuming another’s role as learning experience, identifying with those completely different and foreign is repeated many times over, but Uchida’s script can’t be pinned down as just that, just as it is both a romantic quest and a situation possessed with knowledge of the rules of that quest.

This shifty approach comes through in one of the movie’s sweetest lines. As one character asks another if they want to become friends after a short time spent together, the reply is “But we’re friends already, aren’t we?” Right from the first scene, we’re in a universe of pre-ordained weddings, loudly-stated humour, and extra real, or obliviously real, emotion.

Kenji Uchida displays a refined sense of timing and plotting, a visible distance from his time-hopping first widely-seen feature A Stranger of Mine. Visually, there seems very little to distinguish Key of Life, but when Uchida steps back and lets his actors Act in a long take that is both invisible and a loud comment that this is unbroken acting, it’s clear this is a step beyond the norm. In its dense and denser plotting, delivered as just that, Key of Life is to its demise/triumph, a knowing comedy. This self-knowledge, the shattering of the illusion, means no regular resolution can be satisfying – the plot twists and twists, but cannot escape its genre constraints, eventually settling for an ecstatic myth, tempered by an exasperated sigh. In any case, they’re both outsized reactions to botched from the start plans, which is what, as each of the movie’s three main characters are introduced, all anyone is looking for.

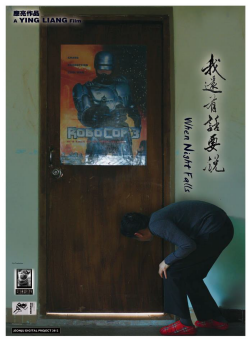

When Night Falls (China)

[In the final paragraph of this review, the ending of the film is discussed.]

Like This Is Not a Film last year (and this year), When Night Falls is a film that grows in importance and political significance when the conditions of its production become known, but even without that knowledge is still a tremendously vital, sensitive and brave work of cinema. Accused of multiple murders at a police station, Yang Jia, son of Wang Jingmei, is given the death verdict, despite incomplete investigation into the event and those it involved. As replayed in the film, the delivery of this message is as regimented, listed, inordinate unstopping pronouncement of paperized characters, figures, without stop until sections [all] and verdict [final] are announced. “[This] is not to be explained.”

Director Ying Liang recreates these actual events from 2008, depicting an environment that is outwardly indifferent to complaint. Frames of space in which people are seemingly able to move spontaneously hold figures at a distance. Accelerated entropy decides where everything is headed as blackened artifical light barely lets out an auburn glow.

It is the mother, Mrs. Wang, that the film follows, as she attempts to provide her imprisoned son with clothing, legal support, and her own measure of unceasing defiance. As connective tissue and moving strength of the film, Nai An gives an immeasurable performance. With only her movements as she reads a letter and handles a plant in When Night Falls’ opening scene to observe, Nai An as Wang Jingmei conveys everything before she finally speaks out, and the entire film rests on this ability to comprehend when there is only the wind outside and silence in. The history of cinema is filled with mother figures of strength, and it is not hard to imagine the lengths Mrs. Wang would go to with those as a reference, but the static, unfeeling repetition of the frame takes her resemblance to become that of Jeanne Dielman, powerless – in one unbroken shot alone, sitting, partly illuminated, emotional, but all internally.

This could be taken for listlessness, as in When Night Falls’ final scene, as Ying refuses to cut away as hands find confined action in drinking and rending of the pages of a calendar. What is the purpose of all this? As eyes search the screen for something noticeable, changing, there is the clock on the wall, presumably for the seconds, then minutes to be counted, defining this closing as an interminable shot if one is waiting for something to happen – but it is, and it has. If it doesn’t dawn until the final title appears what has just happened somewhere Mrs. Wang cannot be, then that experience, in part, mirrors the encroaching realization of her own mind. The over and over tearing of the days could be taken as some kind of symbolism, but it is, more than anything a futile, disregardable action, where repetition turns motion into forgotten meaningless space, with only thoughts and the static, same darkness everywhere beside. Of all the deaths in cinema, this one might be the truest, the un-simplest, for aside from the mawkish death bed, how does anyone recall the moment someone departs, what action can be done against the force that brings this about? This is not an all-encompassing film, but a specific, lived one, that is, in my experience, difficult to hold in a complete, definable way, and yet one I find myself inescapably connected to, and not in a dour or depressive way, even after the lights come up.