By Megan Lambert (The Cascade) – Email

Print Edition: November 19, 2014

The “batcave” is on the top floor of Abbotsford’s A building, up a single flight of stairs.

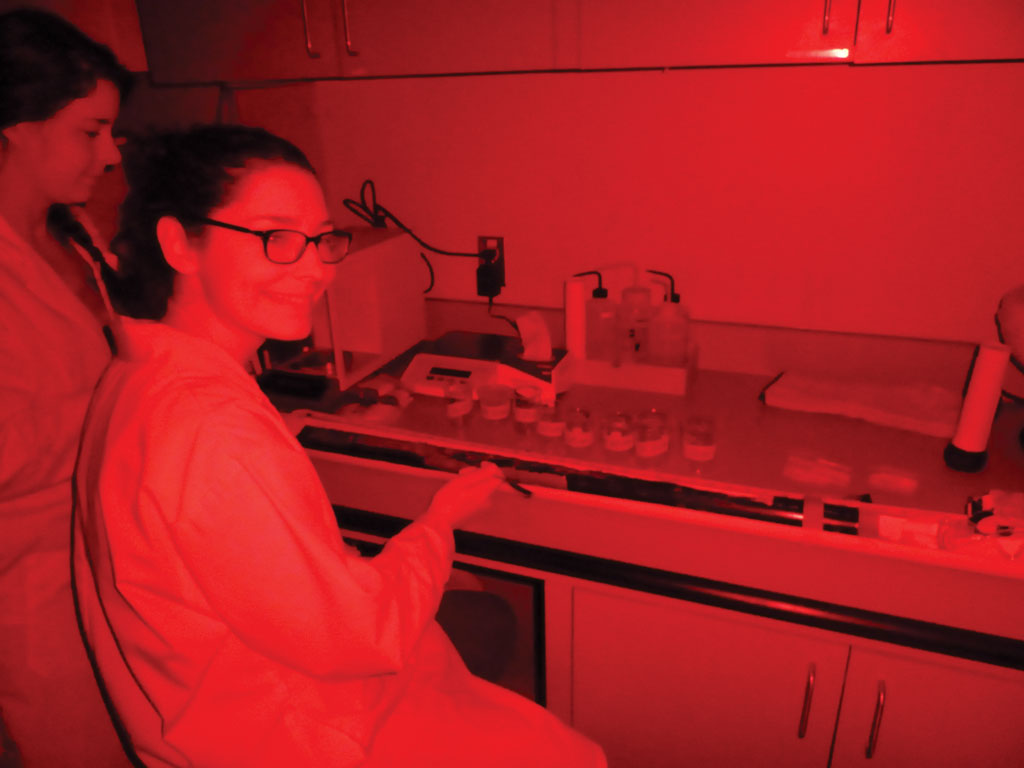

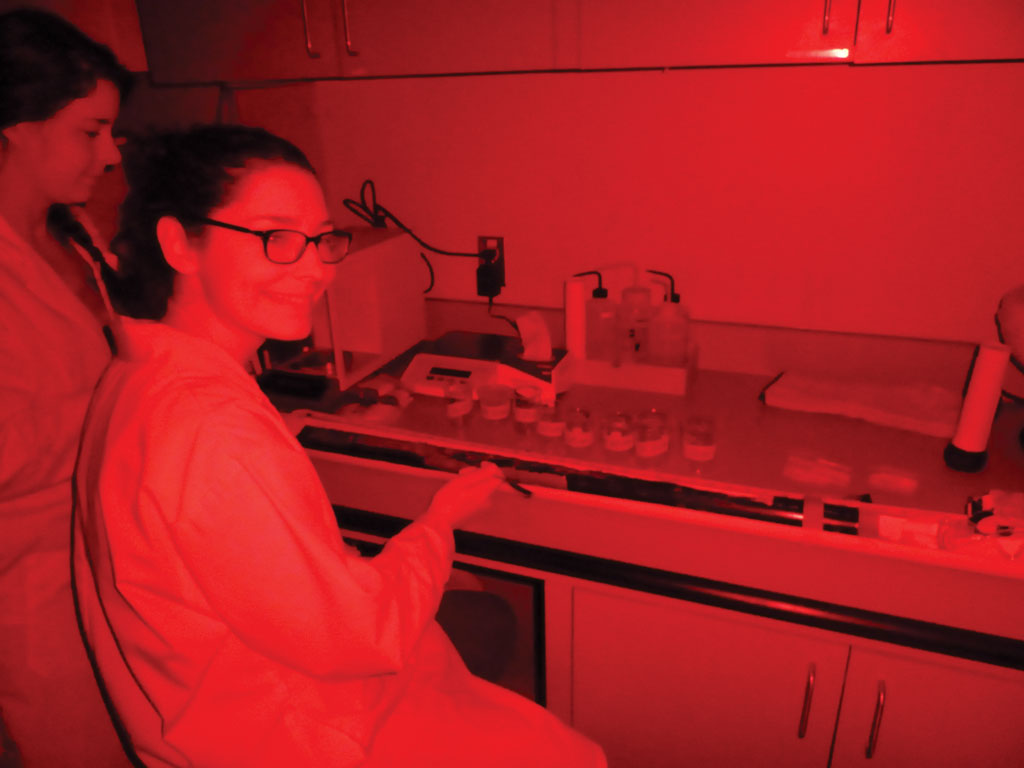

Hidden behind a two-way darkroom door decorated with stuffed bats (toys, not taxidermy), Libby Griffin, Jordan Bryce, and Maureen Eyers analyze grains of sand in near darkness.

Griffin is a recent UFV graduate pursuing her master’s at SFU, and Bryce is planning a similar route, hoping to get her Ph.D.

Eyers’ geology fieldwork has taken her to the Arctic, Greenland, and BC.

“I do geophysics,” she says. “We use different machines to blow holes in the ground, seismic explosives, all that stuff.” Eyers adds that even though she has worked in the geography field for years, she’s also looking to incorporate her degree into her work outside the university.

Using a Risø TL-OSL reader with a beta irradiator, the geography students date sediment — taking samples of sand and analyzing how much radiation they emit. Bryce explains the process: Grains of sand are exposed to light, and the electrons recombine at the centres, giving off excess energy as luminescence. The machine measures how much luminescence the particles give off, in order to know how many electrons were in a sample.

(Image: Libby Griffon)

“It’s crazy to think about, because you can’t see it in a grain of sand,” Griffin says, “but it’s holding all of this energy.”

The machine prints out a graph, and with data analysis geologists are able to calculate the age and the last time they were exposed to sunlight.

“Once it goes into the machine we get all this data and it takes a lot of interpretation, a lot of data analysis,” Griffin says.

“It doesn’t just spit out, ‘Oh, this is 2,000 years old,’ unfortunately.”

Working with the Hakai Beach Institute and a group of students from UVic’s geography department, students like Griffin, Bryce, and Eyers hammer aluminum tubes into dirt or sand cliffs to collect the sand — which they then douse in hydrochloric acid to remove any organic or biological matter.

In an even darker room attached to the whirring Risø machine, the wet lab is where they manually sift through the sand to separate quartz and felspar — Earth’s most common minerals. Griffin notes that quartz lets off a small amount of light, making it difficult to track data.

They use the liquid lithium metatungstate (LMT) to separate the two further. The grains are then treated with an acid to smooth over any erosion or impurities, and are made similar sizes to keep the data consistent.

The data from coastal BC — places like Haida Gwaii and Quadra Island — can be collected into a larger pool to help track tides and climate over thousands of years. “It can tell us about past environmental change,” Bryce notes.

For her honours project, she says, “I’m going to be dating this ancient beach sand that’s buried, so it can tell us that sea levels were high enough to form a beach at that location.”

Griffin says that her work at UFV started with a Friday morning class she shared with Eyers — their prof and now supervisor, Olav Lian, opened up student positions for lab work.

“It’s great that UFV has these opportunities,” Griffin says — and just like the bat cave, “I think a lot of students have no idea that they even exist.”