Founded by Reverend Fred Metzger, a pastor and teacher who sheltered Hungarian Jews during World War II, The Metzger Collection is free to the public and can be found in Columbia Bible College in Abbotsford, B.C.

Metzger immigrated to Canada in 1950. Attending Expo 67, he was inspired by the idea of a biblical museum. After a career as a Presbyterian minister, he founded the Biblical Museum of Canada in 1980. Metzger’s worldly travels inspired him to collect replica artifacts from Sumerian, Egyptian, Biblical, and classical antiquity, spanning to the Middle Ages to modern history. In 1997, he was honoured with a Doctor of Divinity degree from the Presbyterian College at McGill University. After his death in 2011, the Biblical Museum of Canada was moved to the Columbia Bible College in 2012 and renamed The Metzger Collection.

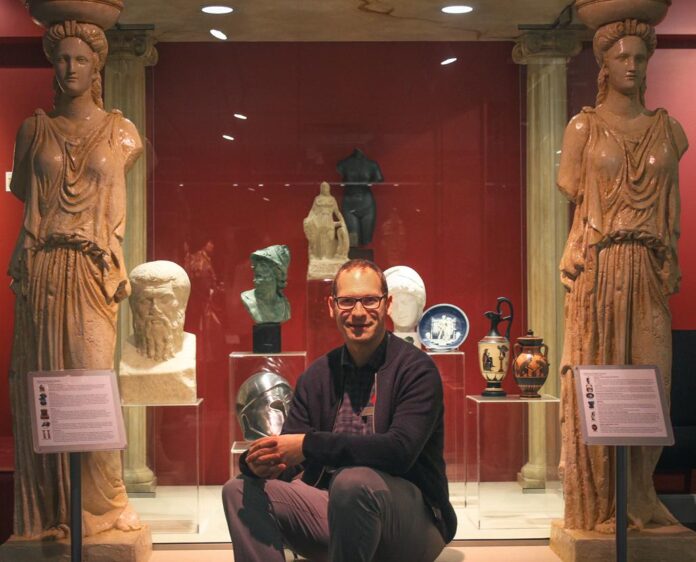

Greg Thiessen, practical theology program director, Metzger Collection manager, and assistant registrar, shared his thoughts with The Cascade on the uniqueness of replica museums and their potential for accessible learning.

“I would travel around the world to see the originals of these [artifacts],” said Thiessen. “But there is something about replicas that is also greatly of value.”

Having a replica museum here in Abbotsford gives the community the opportunity to access these unique pieces without having to travel to far-off destinations to view them. Even if they aren’t the real thing, artifacts are still works of art; Thiessen commented on how replicas bring history to life just as much as the original.

“There’s an element of beauty [and] fascination that comes through seeing artifacts rather than simply information. There’s something about the artifact that interacts with our imagination and our creativity and there is an incredible opportunity with that.”

Replica artifacts are also less costly to insure and, if damaged, can be replaced at an affordable price.

“I think they’re actually great,” said Aleksandar Jovanovic, an assistant professor in history at UFV. Jovanovic is all for the idea of replicas, especially when it comes to areas of history that are farther away from the learner. Replicas bring history into the hands of the learner.

“Specifically North America, where for ancient or pre-modern stuff from around the Mediterranean, the Greco-Roman, Egyptian, Babylonian, or whatever other, we had very little to engage with in terms of material.”

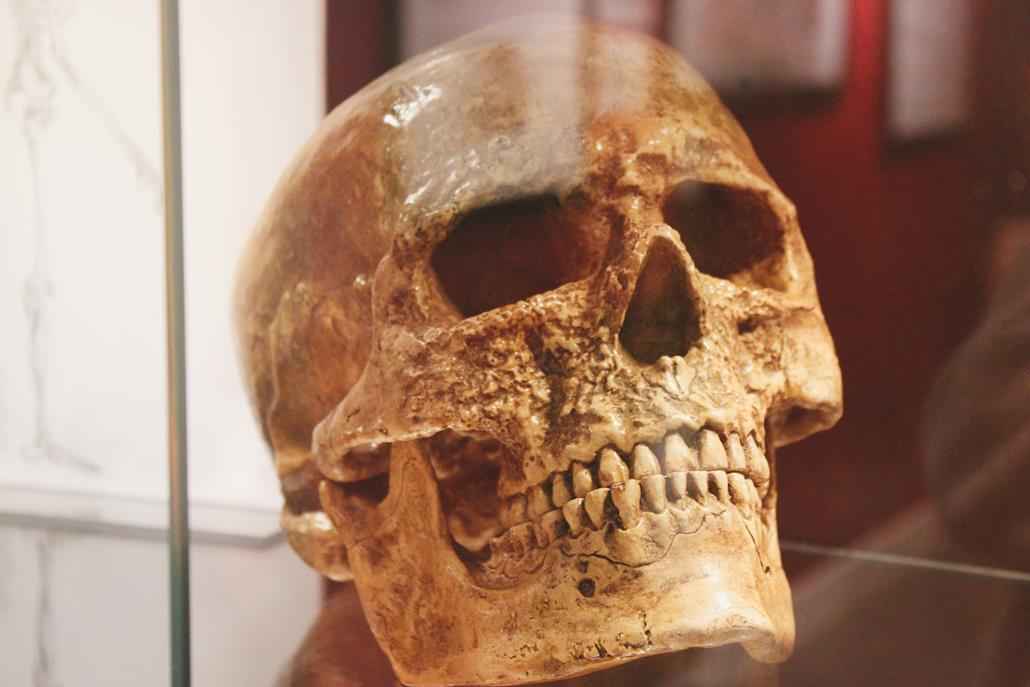

Artifact replication is not a new notion, especially in ancient civilizations when travel was even more difficult.

“Romans were [very] much into the replicas as well. It was part of their world, too. Not every[one] could have access to every single original. So they were making replicas all around the empire. They make this sort of history more accessible,” Jovanovic shared.

The accessibility of replicas extends beyond geography; their interactive quality is an aid for visually impaired learners.

“You can have a tactile feeling of how an object was made, how it looked, its shape, things like that. So it does bring about quite a bit in terms of accessibility [to] the past [for] students with different types of learning,” Jovanovic said.

Moreover, replica artifacts bypass issues of rightful ownership because they are only a copy of an original. Thiessen also posited that replicas offer a solution to the growing demand for artifacts to remain with and be returned to the cultures that produced them.

“[It’s a] matter of justice … so many of the artifacts that can be found in museums around the world are not native to that place … especially European museums.”

This injustice is not just something that happens in Europe. Canadian museums for a long time have been accused of the same thing.

“This is also very much an active issue in our own [Canadian] context with Indigenous artifacts and movements of repatriation. These [artifacts] should go back to the peoples to whom they properly belong. Replicas bypass that issue of justice,” Thiessen stated.

In the world of replicas, most pieces are acquired from the museums that are home to the originals. Certain replicas are 3D printed by places like the Smithsonian Institution and the British Museum and are easily obtainable. Theissen mentioned that The Metzger Collection museum buys authentic replicas from these institutions while other pieces are procured from various private organizations specializing in artifact replication through practices like moulding.

“In some cases, Fred Metzger was given permission to make a mould off of the original and produce his own replica,” said Thiessen.

Thiessen is proud of the accessibility and diversity that the Metzger Collection offers through its unique replicas.

“The Metzger Collection is the only place in the world [where] you will see all these pieces under one roof.”

While that may be true, The Metzger Collection isn’t the only museum that puts an emphasis on replicas in B.C. Colossal Creations is another replica museum based in Coquitlam that mainly features replica paintings you can only find in places like the Louvre. Replicated masterpieces like Leonardo da Vinci’s The Lady with an Ermine (1490) and Johannes Vermeer ‘s Girl with a Pearl Earring (1655) hang on its walls. There’s even a replica of the Mona Lisa (1513).

Cosimo Geracitano is the man responsible for all the replicas housed in Colossal Creations, which is also the home of Geracitano. Called “painstakingly precise” by CTV News, Geracitano is dedicated to the art of reproduction. His reasons for housing replicas are quite different from that of The Metzger Collection.

“Obviously, I cannot buy them, as they are too expensive and they are not for sale, but I want them in my house, so I paint them and now they are here for me to look at every day.”

Geracitano’s replication process is particular, as he attempts to get into the same mindset of the painter at the time they were painting.

“I’m trying to make an exact copy in the condition it used to be when the artist just finished the painting,” he told The National Post. “I’m not only replicating, I’m restoring, too.” Unfortunately, the museum is closed to the public until March 2025, so The Cascade was unable to see the museum in-person.

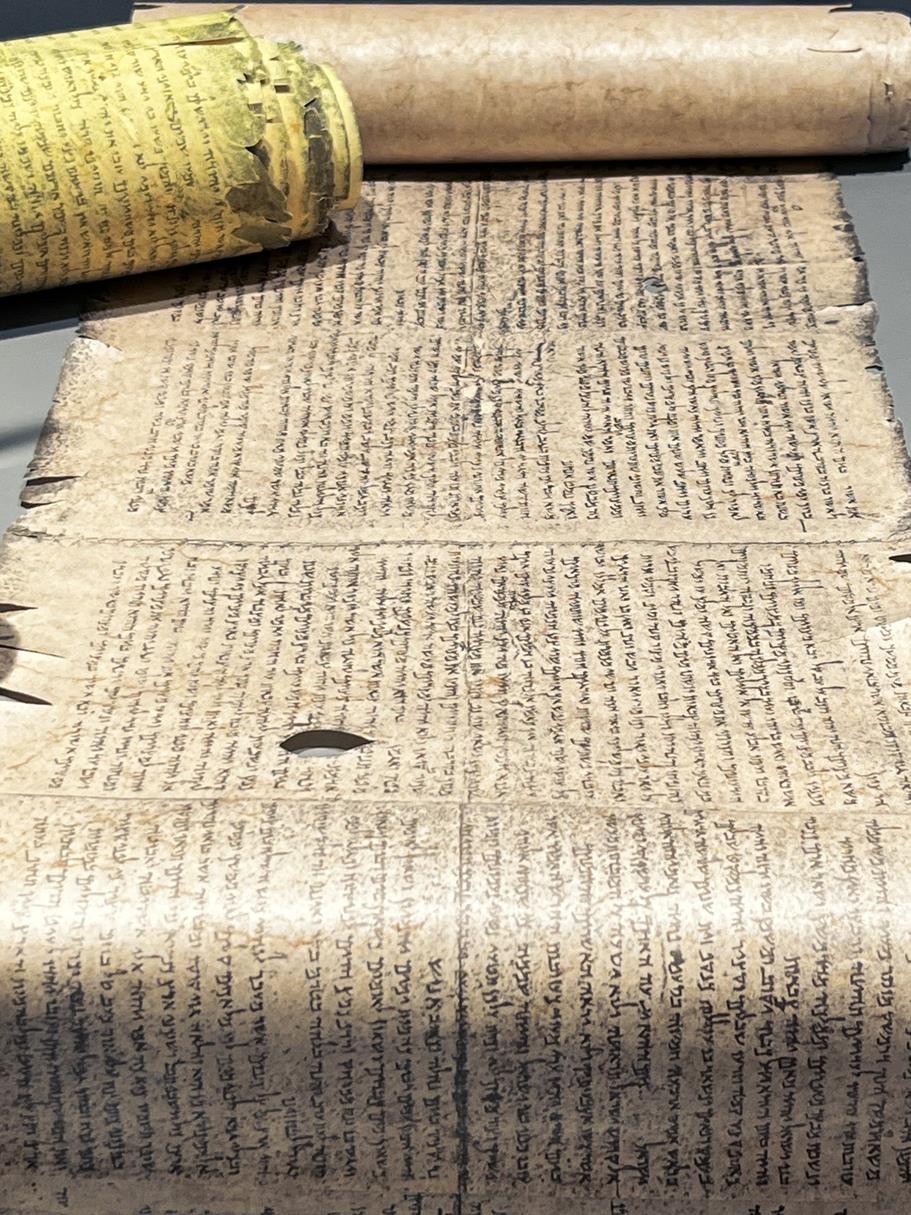

The Metzger Collection has recently launched a display on Martin Luther’s Reformation, titled 1525: Reform and Revolution*, an in-depth visual exhibit of the history behind the movement, specifically focusing on the year 1525, which Thiessen believes was when the reformation officially took off, challenging the status quo and affecting areas of politics and society.

“I typically would do one big exhibit like this one that starts in September, and then one smaller exhibit in March of [original] artwork of Columbia students.”

There is a certain criticism and prejudice that comes with being a replica museum; Thiessen emphasized the importance of how a replica is displayed.

“A replica will look cheap if it’s cheaply displayed … What I really value is that they made this space into a very professional looking museum space. These are beautifully housed artifacts and so there is that level of elevation of the replica that comes with that.”

The fact that these replicas don’t have the same prestige as their real counterparts shouldn’t negate their importance; Thiessen explained how value isn’t always about how old the object is, but what it can offer.

“Part of the value is the story that these artifacts tell, even if the value is not in the artifact itself and so [we try] to point toward the story rather than ‘look at this incredible treasured object.”

The role of the historian is vital in the discussion of replicas; Thiessen shared what he thinks historians’ attitude toward learning should look like.

“I firmly believe that the posture of the historian must be one of humility and learning … our approach is not one of judgement. It’s one of learning and listening. I think that is incredibly important to have that posture of a listener, of an observer seeking to understand … The collection [is] very geared towards hands-on learning, we are not just for school groups. Museums are not everybody’s thing. I recognize that museum fatigue is a real thing.”

History is a field of study mainly associated with textbooks and heavy non-fiction reading; Jovanovic reiterated how important it is to have museums, so we can see things from the past, rather than only reading about them.

“Historians rely on texts, but I think material culture can tell us quite a bit about the lives of the people, beyond the kind of high politics of the few people who were members of the political elite.”

The Metzger Collection is free to the public, removing a barrier to access that often comes with large historic collections.

Whether or not you are a student, everyone is a learner, and there is always more to discover that can impact the way we think and live. Engaging with history, replicated or otherwise, offers meaning and purpose. Thiessen’s message to the local community is clear: there is still plenty for all to learn.