These issues have deep roots that arise from systemic racism due to settler colonial practices surrounding the normalisation of whiteness, whilst also being deeply imbedded in misogyny due to Canada being founded and built upon patriarchal principles. As such, the endemic of missing and murdered Indigenous women in Canada must be viewed in a way that considers both race and gender and how these two identities intersect in order to ascertain how these tragedies continue to happen, and why there are such high instances of violence against Indigenous women. Moreover, the racism and sexism that allows violence to continue against Indigenous women is not always blatant and easy to dissect, often presenting itself in insidious ways. All of these factors need to be considered as part of a larger picture to see how they are inherently and intrinsically linked to white and male normative ideals within society.

The historical context of how Canada became colonised is essential in understanding violence against Indigenous women. Canada is a settler colonial country, whereby Indigenous people have been persecuted with the overall hope of eradication or assimilation. As such, it is crucial to consider that Canada is structured around principles that were designed to allow colonisers the opportunity to hold power and ultimately acquire land and keep that land for themselves. Therefore, many structures within Canadian society not only exclude the voices of Indigenous people, but they also actively work against Indigenous people — and this is not a sociological coincidence, but instead the entire purpose of how the society was and is structured. Although the history of settler colonialism is important in understanding how whiteness became normative within today’s society, settler colonialism is in no way a “thing of the past.” While settler colonialism may bring about connotations of past practices, all non-Indigenous people living on stolen land (otherwise known as unceded territory), even in present day, are colonial settlers. Moreover, it is imperative to acknowledge that colonial settler ideology is still prevalent and is still currently working to benefit white people within society.

The RCMP’s role in upholding, maintaining, and assuring the continuation of settler colonial rules and ideals

One such institution within society that benefits colonial settler rule is the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP), whose purpose is to enforce laws made by colonial settlers. The police were not created for or with the safety of Indigenous people in mind. Moreover, the police are inherently necessary in order to uphold, maintain, and assure the continuation of settler colonial rules and ideals, and it can be argued that Indigenous people are often seen as a threat to those ideals.

The judicial system and law enforcement often work against the safety of Indigenous women in a twofold manner: firstly, Indigenous women may not trust the police to help them, as they are often penalised by the legal system and harassed or assaulted by the police. Similarly, while Indigenous women only make up 4.3 per cent of the Canadian population, they account for nearly 50 per cent of the federal female prison population, a vast overrepresentation. Moreover, while the overall number of incarcerations is currently declining, incarceration rates of Indigenous women remain incredibly high and are increasing, further highlighting the rampant inequalities prevalent in the modern Canadian justice system.

Often, the belief that police will be indifferent to crimes committed against Indigenous people can lead to a furthering of violence against Indigenous women by male perpetrators, as they may believe that they will be able to get away with any crimes committed. This dynamic can lead to Indigenous women becoming isolated when a crime has been committed against them, as they may feel like they have no recourse for action. In addition, this can also cause seclusion of families and loved ones of missing and murdered Indigenous women, as they may feel they cannot turn to the police, or that the police may not work as hard to resolve these cases. It is important to remember that the police were not designed to uphold Indigenous norms and values, nor was the government set up by Indigenous people, who do not have control over how either of these systems choose to enforce power over them. Consequently, as these two institutions work in tandem, it may often feel like there is nowhere to turn for help, for change, or for Indigenous voices to be heard, especially if these violent acts are committed by the police or if the police do not give due care to cases involving Indigenous people.

Elisha Corbett, the manager of the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (MMIWG) department of the Native Women’s Association of Canada (NWAC), discussed in an interview the invalidation families feel when they report an Indigenous woman as missing and how the RCMP abets this cycle of violence.

“The RCMP won’t actually say that they are missing; they will say that they were a runaway, and that is so problematic for so many reasons,” said Corbett. “For one, it is very invalidating if the family is saying ‘I’d hear from my daughter every week and I haven’t heard from them in a month.’ If police officers have this preconceived notion about Indigenous women, they will say, ‘Oh, she’s a sex worker, she’s a drug addict, and it’s normal for individuals who live this sort of lifestyle to be out of contact,’ and they’re not really listening to what the family is saying.

“Not only is it invalidating, but if they are not categorised as a missing person, no action is done to look for them, and it actually allows the cycle of perpetrators to continue to target Indigenous women, because they know that the RCMP or the Canadian government does not take these cases seriously. It is an all-encompassing issue. This also relates to human trafficking; if an individual is reported as a runaway, yet they have been human trafficked, it allows traffickers to continue to target Indigenous women — because they not only think, but they know, that their disappearance isn’t going to be taken seriously or looked into as much.”

The documentary Finding Dawn illuminates the way Indigenous people often have to strive to make themselves heard by the police regarding the disappearances of loved ones. Ernie Crey, an advocate for missing and murdered women and the brother of Dawn Crey, a missing Indigenous women believed to have been murdered in the Pickton farm case, states in the documentary, “[referring to the Pickton case] If it involved largely white women… the investigation would have been thorough going, it would have been well financed, there would have been a lot of police officers… and we very likely would have had a suspect in jail far earlier than was the case where all of these missing women were concerned.” This sentiment is reinforced by the recent media attention surrounding the murder of a young white woman, Gabby Petito, who was missing for several weeks beforehand. Petito’s disappearance showed a media frenzy that was global in scope, unlike any media attention garnered for missing or murdered Indigenous women. This type of media attention to the Petito murder in the United States still ardently proves that “Missing White Woman Syndrome” is ever present, even globally.

Socioeconomic factors directly caused or exacerbated by colonial settler ideologies that cause violence against Indigenous women

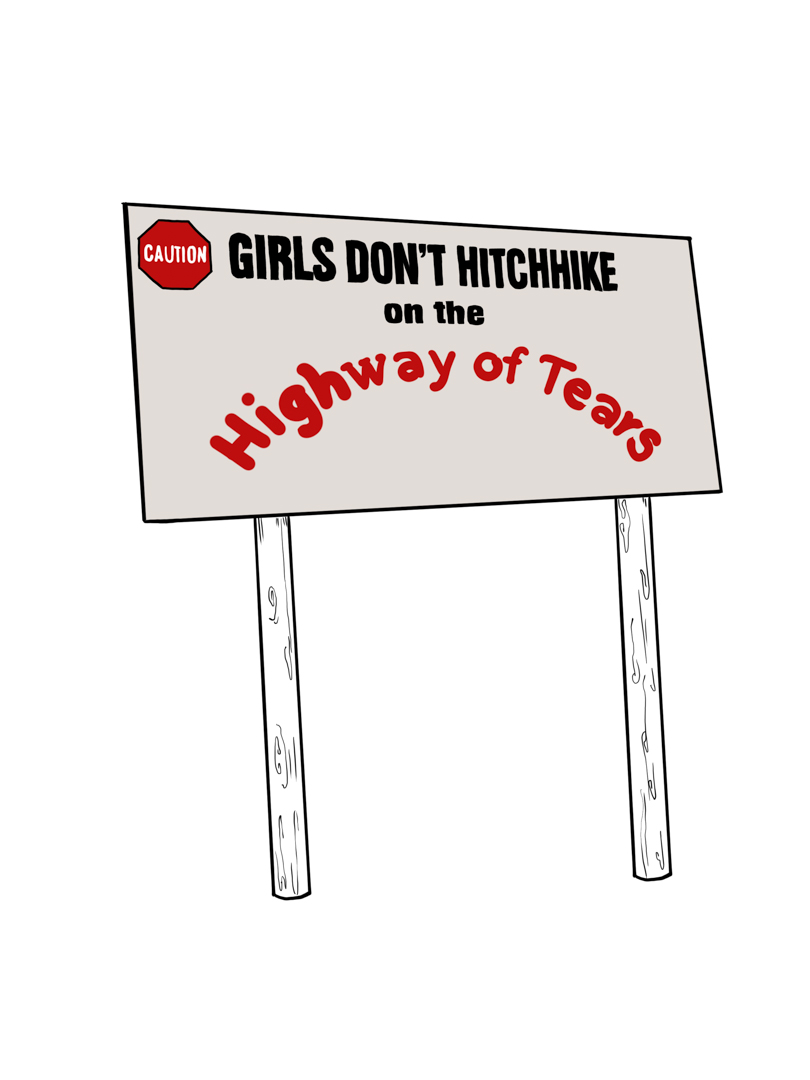

In addition, poverty and lack of resources, poor mobility, and the secluded nature of many Indigenous communities are all contributing socioeconomic factors as to why Indigenous women may be more likely to be victims of violence. All of these components have either been directly caused by or exacerbated by colonial settler ideologies, practices, and values. One way in which colonial inequality can be witnessed is through a lack of adequate mobility and poor public transport, most notably along Highway 16, which has resulted in several murders of Indigenous women, leading to the highway being known as the “Highway of Tears.” In addition to inadequate public transport along the highway, it is also important to consider that public transport is a financial expense that not everyone can afford, and this can result in the need to hitchhike or look for alternative modes of mobility. While not all victims on the Highway of Tears have been Indigenous, nor has every Indigenous woman who has been on the highway ended up missing or murdered, the reasoning surrounding why so many Indigenous women have gone missing is incredibly relevant.

In addition, poverty and lack of resources, poor mobility, and the secluded nature of many Indigenous communities are all contributing socioeconomic factors as to why Indigenous women may be more likely to be victims of violence. All of these components have either been directly caused by or exacerbated by colonial settler ideologies, practices, and values. One way in which colonial inequality can be witnessed is through a lack of adequate mobility and poor public transport, most notably along Highway 16, which has resulted in several murders of Indigenous women, leading to the highway being known as the “Highway of Tears.” In addition to inadequate public transport along the highway, it is also important to consider that public transport is a financial expense that not everyone can afford, and this can result in the need to hitchhike or look for alternative modes of mobility. While not all victims on the Highway of Tears have been Indigenous, nor has every Indigenous woman who has been on the highway ended up missing or murdered, the reasoning surrounding why so many Indigenous women have gone missing is incredibly relevant.

As researcher Katherine Morton succinctly claims, “Without being caught in a trap of essentialising experience, it is clear that something deeply problematic with regard to the intersection of race, gender, and mobility is resulting in a high number of female Indigenous hitchhikers facing violence.”

Morton also discusses how the 2006 Missing and Murdered Women’s Symposium suggested placing billboards along the Highway of Tears with important information and helpful numbers to contact. However, the government did not follow the advice given on how best to construct the signs, and chose to chastise hitchhikers instead. As such, the government showed ineptitude in responding to the root causes that lead to the need for hitchhiking, and ultimately more instances of violence. The government opted to erect billboards advising against this mode of transportation altogether. This not only does nothing to solve the underlying societal problems, but puts the onus on Indigenous women, who may have no other option outside hitchhiking.

“That type of girl” who is less deserving of sympathy, media attention or police time

Another facet of victim blaming, which ties together with a lack of media and police interest, is when the victim is deemed to be “deserving” in some way. Moreover, notions of femininity are socially constructed in order to benefit white women. As such, women who do not fit into this view of femininity are often depicted as “lesser.” This shows that Indigenous women are at the intersection of both race-based and gender-based inequalities. This constructed view of femininity portrays white women as “passive” while simultaneously depicting all other women of differing racial identities as “aggressive.”

Journalist Sarah Stillman discusses the lack of media attention around racialised victims of violence, stating, “Each day, the mainstream media provide audiences with a subtle instruction manual for how to empathise with certain endangered women’s bodies, while overlooking others”. The mainstream media upholds narratives surrounding who is deserving of attention, which is often white people, leading to further “othering” and discrimination against already marginalised BIPOC communities.

A common theme of Indigenous representation in the media is that they are often underrepresented when crimes are committed against them, or they are represented as inherently violent, leading to apathy. This further compounds the victim blaming that is ever-present against missing or murdered women who worked within the sex trade, with little to no societal concern when violence is committed against them. Discourses surrounding missing Indigenous women and sex workers can lead to worrying conclusions that some lives seem to hold more worth than others, or that some people are more “deserving” of being victims. As such, it is essential to change these discourses and to be cautious of the content of mainstream media.

“In terms of settler colonialism, since contact, since colonisation began, Indigenous women have been misrepresented in this way that allows the general public and the Canadian government to excuse the violence that they experience,” said Corbett, who alongside working with the NWAC is also doing her PhD in media representations.

“Settlers came in with this very colonial and Christian view of what womanhood is and what motherhood is, and anything that went against that Christian settler colonial view of that was seen as bad. So Indigenous women who didn’t fit into that Christian model of motherhood or womanhood were portrayed as this really terrible slur, essentially this stereotype that they are ‘dirty,’ ‘immoral,’ ‘unworthy,’ and therefore, any violence that they experience can be swept under the rug. We still see that today. If you look at the coverage of missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls, almost all of it focuses on the fact that they were ‘living a high-risk lifestyle’ and they will say ‘She was a sex worker, she was a drug addict.’ Therefore she was almost deserving of whatever consequences come from that lifestyle, without actually looking at the larger social and economic structures that contribute to some Indigenous women engaging in sex work or having high levels of addiction or poverty.”

“It’s also this colonial mindset of looking at the individual rather than looking at the collective; the way that the current colonial media frames Indigenous women is that it is an individual responsibility, it is an individual who ‘chose’ to engage in a high-risk lifestyle and it was an individual who perpetrated the crime, rather than looking at the larger collective social issue that for a host of reasons have led Indigenous women to be living in higher risk of poverty, drug addiction, etc. It’s not just one individual perpetrator; it is this entire social issue that is a genocide, so that’s one way I think colonialism has really impacted how the media frames and reports on this issue.”

Make way for Indigenous voices to be not only heard, but prioritised

In order to decolonise and decentre whiteness, the voices of Indigenous women not only need to be amplified, but they need to be represented within the media, politics, and be at the epicentre of societal change.

Indigenous grassroot initiatives, such as Idle No More, and activism and movements much like the annual Women’s Memorial March in Vancouver are integral in impacting change and amplifying voices. The annual Women’s Memorial March garnered mainstream media attention recently for the pulling down of a famous racist statue in Vancouver’s Gastown district, just blocks away from the city’s epicentre of violence and poverty.

When asked if there were any ways in which non-Indigenous people could help amplify Indigenous voices without overshadowing Indigenous activism, Corbett’s advice was to first read the National Inquiry’s Final Report and the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s Calls to Action.

“I think the most important thing an individual can do is really recognise and understand their own biases and their own falsehoods that they’ve created in their minds about Indigenous and non-Indigenous relations, because then that will impact how you walk through the world and then how you interact with everybody,” said Corbett.

“I think too, in terms of doing activism with Indigenous people, it is just that it is ‘with’ and not ‘for;’ it is ‘nothing about us, without us,’ that’s the saying. It’s not speaking on behalf of Indigenous peoples, but it is really amplifying those voices when you have that opportunity, or when you are in a space and you realise there are no Indigenous people there where there really should be — bring Indigenous peoples into the room. If you are able to break a glass ceiling, then don’t just break it and let all the pieces shatter to all the people below you who weren’t able to break through; bring somebody up with you.”

The infrastructure of Canadian society remains problematic, as there is a massive power imbalance between Indigenous groups seeking to have their voices heard and white systems of control, which uphold whiteness as dominant. Additionally, those who are politically in charge are not representative of Indigenous people. Ensuring Indigenous voices are not only heard, but prioritised, especially in regard to their own safety and wellbeing, is paramount. While activism and feminism are necessary in order to overcome the patriarchy, feminism should be inclusive of Indigenous voices, as feminism can often work to protect white women within a colonial framework. If feminism is too narrow in scope, then it is not truly inclusive, and as such, not advocating for true equality.

When asked in what ways race and gender intersect to contribute to the inequalities felt by Indigenous women, Corbett stated, “You can’t disentangle the two; race and gender go together to create the experiences and the way that Indigenous women walk through the world. You can also look at it in terms of Indigenous women’s reproductive sovereignty and reproductive justice; Indigenous women are far more likely to experience negative birth outcomes, they are far more likely to be targeted for birth alerts for having their children taken away from them, they are still having forced sterilisation through coercion, and that is intimately tied to the fact that they are not only a woman, but they are an Indigenous woman.

“We can also tie this back to media representations; if we continuously portray Indigenous women as unfit mothers within the confines of settler colonialism, then the Canadian government can forcibly remove children through the Sixties Scoop, through residential schools, and even now, Indigenous children are significantly overrepresented in child welfare services. Therefore, you can’t really separate the two, because those two parts of identity are really a mesh together to shape the way Indigenous women are viewed by the settler colonial state, how they are treated, and how they are then able to walk through the world.”

All of which highlights the drastic need to work toward decolonisation and the dismantling of the patriarchy in order for social equity to become a reality. If we cease to work towards these goals, then the current social constructs will continue to cause great harm to all those not currently protected by systemic privileges.

Indigenous women are at the intersection of both gendered and racialized inequalities. The high number of missing and murdered Indigenous women in Canada is emblematic of socioeconomic factors brought about through settler colonialism and patriarchal norms and values which centralise both whiteness and maleness. This can be seen through the indifference or the outright violence of the police when dealing with Indigenous communities, the lack of media concern, the societal constructs surrounding femininity, and victim blaming. In addition, social issues such as poverty, lack of resources, and mobility must be looked at as part of the larger picture of systemic racism and as contributing factors in allowing violence to continue to happen by creating conditions that enable it. Therefore, it is essential to work towards the decentring of whiteness, decolonisation, and the abolition of the patriarchy in order to overcome white normative, male-based colonial ideals, which allow both “race” and gender-based violence to remain prevalent. When social changes allow for true inclusivity and equity, then missing and murdered Indigenous women will be met with the same level of care and outrage as their white counterparts.

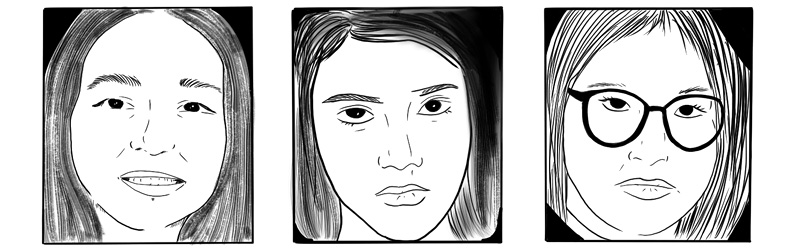

However, while violence is committed against Indigenous women at an alarmingly high rate, Corbett highlights that Indigenous women should not be seen as or portrayed purely as victims, emphasising, “Indigenous women — and this is not to trivialise the fact that they are overrepresented as victims of violence and overrepresented in the prison system, because those are very serious things, but I also do want to emphasise that Indigenous women are resilient, and they are beautiful, and that Indigenous women have a lot to offer the world. When an Indigenous woman is taken away from their family and their community, that whole community suffers, and that culture suffers. We should not just partially look at this crisis, but view it holistically and see the impact that all of this has around the issue of missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls.”

[…] are thousands of murdered and missing Indigenous women (MMIW) across the United States and Canada, and in Montana those numbers are particularly high. Over the past decade, dozens of young […]

[…] are thousands of murdered and missing Indigenous women (MMIW) across the United States and Canada, and in Montana those numbers are particularly high. Over the past decade, dozens of young […]

[…] are thousands of murdered and missing Indigenous women (MMIW) across the United States and Canada, and in Montana those numbers are particularly high. Over the past decade, dozens of young […]

[…] are thousands of murdered and missing Indigenous women (MMIW) across the United States and Canada, and in Montana those numbers are particularly high. Over the past decade, dozens of young […]

[…] are thousands of murdered and missing Indigenous women (MMIW) across the United States and Canada, and in Montana those numbers are particularly high. Over the past decade, dozens of young […]