I caught a taxi at the airport and made my way to The University of Ottawa. The drive through the city was breathtaking. We followed the Rideau River most of the way, taking in the city architecture, roadways, and parks that combined modern and Gothic-inspired Victorian design. The sidewalks were clean and well maintained, and the river reflected a magnificent cobalt blue. The campus was intimidating, more a self-contained city than schoolground. I paid the cab fare, deposited my bags at the dorm, and took off for downtown.

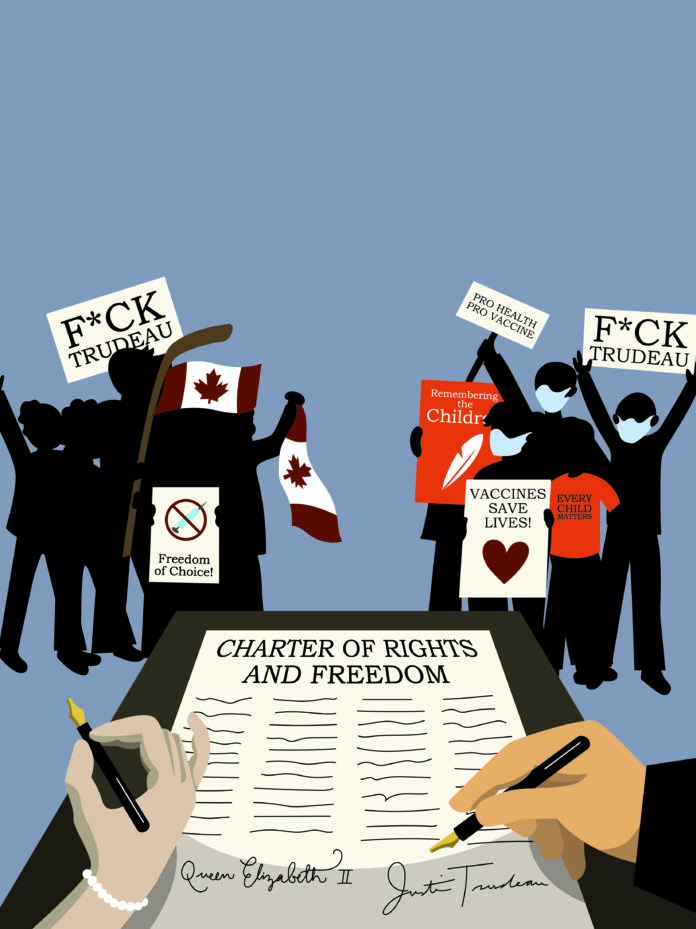

Crowds of people hurried along the streets in different directions. Tourists were checking out the sights and buying maple leaf shaped syrup and fancy coffees in ByWard Market. Locals commuting to and from work passed lingering mandate protesters, entrenched like battlefield remnants. One man drove around on a mobility scooter completely adorned in cardboard signs with anti-vaccine messages, “FUCK TRUDEAU” stickers, and an upside down Canadian flag tied like a cape and flowing down the back of his scooter.

Outside Rideau Hall, across the street from the statue of Terry Fox, a group of men displayed their signs for all to see. One brandished the slogan “GOT VAIDS?”, suggesting that the COVID-19 vaccines were giving people AIDS. The sign disturbed me on multiple levels. Was this man who was spreading misinformation about vaccines, simultaneously attempting to tap back into the panic rhetoric from the 1980’s AIDS crisis, all in-front of a statue of a Canadian icon who died of cancer? I put my headphones on, picked a Weeknd album to listen to on my walk, and journeyed back towards my dorm to prepare for the discussions the following morning.

I was in town as a representative of The Cascade. The student paper had received an invitation from the University of Ottawa to attend a conference in June. The event would take place over two days at the university, located a few blocks away from Parliament Hill. The intention of the conference was to reflect on the 40th anniversary of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. I wanted to go for multiple reasons: to network with other journalists, to be surrounded by aspiring writers, and to learn more about Canadian federal politics. On a much more personal level; however, I wanted to see more of Canada. I wouldn’t describe myself as a particularly patriotic person, especially these days, but I want to see as much of the world as I am able to, especially of my own country.

In light of recent events surrounding the nation’s capital, the uncovering of thousands of unmarked child graves at former residential schools, and Indigenous protests over human and land rights abuse across the country, the Our Charter, Our Rights conference provided an opportunity to observe how far we’ve come as a country since the Charter’s enactment. It also underscores the role that journalists and lawyers can play in actively shaping our society.

Reflecting on what I saw downtown left me confused and frustrated. For one, I still wasn’t entirely clear on what the Freedom Convoy movement really stood for. Asking people on the street hadn’t provided any clarity. Some said restrictions (most of which had already been lifted with the rest soon to follow), while others denounced experimental vaccines. I struggled to fall asleep that night as I pondered what might be discussed the following morning, and what questions I might have for our federal leaders attending the conference.

The Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms was enacted in 1982 and makes up a part of Canada’s Constitution. It details the fundamental rights of all Canadian citizens — rights that include, but are not limited to: the right to peaceful assembly, the right to work and make a living, the right to leave the country and travel domestically unimpeded, and the right to own property. The Charter protects these rights of Canadians from legal interference and discrimination.

The Charter has become a major source of pride for many Canadians, and perhaps rightfully so. The document acts as a blueprint for our primary values as a country and showcases a commitment to recognizing human rights. Since it’s formation, there have been amendments made such as the right for all citizens to legally be married, regardless of gender and sexual orientation. As our country grows and develops, the values expressed in our Charter rights should grow with it to continue protecting all citizens from each walk of life.

The conference felt like a deep immersion into Canadian politics. People who I previously never thought I’d share the same floor space with were suddenly standing only a couple of feet away from me — there to share dialog about the state of Canadian human rights policy development. Among the many guests we heard from was Paul Champ: one of the primary lawyers litigating against the Freedom Convoy; Elizabeth May: former leader of the Green Party and current Member of Parliament; Natan Obed: President of the Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami; and refugee Mexican journalist Luis Horacio Nájera: author of The Wolfpack. Each speaker brought their own perspective on Canada’s current state of action regarding human rights policy.

Kicking off the event, Champ spoke on the fundamental misinterpretation of The Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms that fueled the actions of those within the Freedom Convoy; namely, the right to peaceful assembly. Champ drew upon examples of actions taken by members of the convoy that caused direct harm to residents of downtown Ottawa including physical and psychological injuries sustained from excessive honking and the torment of sleep deprivation caused therein. He explained that simply identifying one’s movement as “peaceful,” and declaring one’s right to freedom of assembly does not protect an individual from litigation and legal enforcement if their accompanying actions are not in line with the commonly understood definition of peaceful.

The right to peaceful assembly as outlined by the Charter came up numerous times throughout the event. We had copies of the Charter on us, and I read it in its entirety. Something that stood out to me was that within the Charter, it outlines very simply, one’s right to peaceful assembly. However, there’s no additional commentary on what peaceful assembly looks like nor how it would be respected by Canadian law enforcement during times of demonstration. Without stating in explicit terms where one’s right to freedom of peaceful assembly begins and ends, the door is open to interpretation.

The Charter provides a framework for legislators and legal experts to interpret and codify. For example, the Charter does not explicitly legalize access to abortion, but protections under Section 7 states, “everyone has the right to life, liberty and security of the person and the right not to be deprived thereof except in accordance with the principles of fundamental justice.” It’s this baseline that provided Canada’s Supreme Court justification to overrule prior restrictive abortion laws in its 1988 R v Morgentaler decision. The Charter is the scaffolding upon which Canada’s representative democracy shapes itself over time, while providing a baseline of fundamental rights and protections.

In the winter of 2022, many Canadians witnessed the events of the Freedom Convoy protest in downtown Ottawa. The polarizing episode saw a massive group of anti-mandate protestors gather downtown in an attempt to force the Canadian government to abandon all COVID-19 restrictions and vaccine requirements. The assembly caught the attention of the international press, with many eyes watching the federal government to see how they would respond. As the pressure continued to mount and the intensity of the situation compounded, the government declared the Emergencies Act.

Despite my strong personal convictions against the convoy protest and their actions, I felt concerns over the precedent that would now be set for how the Canadian government would move to suppress other protests of various causes. This historic moment called into question exactly how far Canada’s charter right to assembly extended, and how closely Canada follows the blueprint set for human rights policies. Canada’s past has been placed under a very bright spotlight in recent years.

The widespread reporting of Indigenous child graves at residential schools around the nation elicited a visceral collective pain and public outcry. Increased attention brought the discussion of Canada’s history as a colonial country to many who had not been aware, or had not reckoned with, the scale and intention of the harm done to Indigenous people over centuries. For many Canadians and outside observers alike, realizations of cultural genocide provided a totally new lens by which to see the country, which has led to anger, dispair, and public protests. The revelation of Canada’s violent and genocidal history feels like a deep betrayal to many. The Charter conference represented an opportunity for students to engage in dialogue that actively shapes the trajectory of the nation, striving to create a better future, while confronting and addressing the wrongs of the past and present.

The first day concluded with the conference splitting up into two groups. Those representing their school’s law programs left with some members of parliament. A small group of student journalists and myself gathered in a classroom on the second floor of the University law building and had a meeting with journalists Luis Horacio Nájera and James Cullingham.

Cullingham is a documentary filmmaker who spent forty years working with the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC) and now runs his own film production company, “Tamarack Productions”. His most recent work, “The Cost of Freedom,” gave a platform to refugee journalists living in Canada under asylum to tell their stories. One of the subjects of the film was Nájera.

Nájera told us his story about exposing the drug trade and murders taking place in the city he lived in. Initially, there were some threats targeted towards Nájera personally via the Cartels, which prompted him and his family to protect themselves by relocating within Mexico. However, an anonymous source reached out to Nájera to advise him that his name had appeared on a hit-list for assassination. The prospect of being killed as a journalist in Mexico was something to be taken seriously, and Nájera needed to act quickly to protect his family.

The work had become too dangerous. Nájera fled to Canada with his family under the cover of darkness. He explained the emotional flood of relief he and his family felt having found safety here. However, since relocating to Canada, Nájera asserts that he has been denied many opportunities to professionally utilize his journalistic skills. Despite receiving advanced degrees while living in Canada, combined with years of journalistic experience, he’s struggled at nearly every doorway into the industry beyond smaller, more inconsequential stories.

I fell into bed that night simultaneously elated and frustrated. Three years prior to this conference, I would not have believed anyone if they’d told me I was going to be sent as a representative journalist for a university paper to the political center of Canada. Being in Ottawa for this event felt validating to me on multiple levels: as an aspiring journalist, as a student of social work, as an autistic individual wanting to make a difference, as a person with severely low self-esteem, as a burned out kid wanting to make their late brother proud. I was overwhelmed simply by being there, and by talking about Canada’s future with the people who would actually be involved in shaping it. Contrarily though, I was frustrated by the internal conflict that surrounded my feelings towards Canada as a country.

I was still pondering the violent actions taken by police against protesters at Wet’suwet’en and Fairy Creek, and the fact that numerous Indigenous reservations in Canada do not have access to clean drinking water. Conversely, we’d heard from refugee journalists about the safety and protection given to those whose home countries sought to have them killed for reporting the goings-on in their localities. Nájera found asylum in Canada, but he is still getting blocked at multiple doorways despite all of his nationally recognized qualifications. Canada is a beacon of safety and hope to those fleeing from danger, but our country is not so far removed from its violent, racist foundations as we might like to think. I pondered all this as I walked into my dorm, climbed into bed, and crashed right to sleep.

The next day we met bright and early, got some coffee, and congregated together in the large conference room. Among many other guests that day, we heard from MP Elizabeth May, and President of the Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami, Natan Obed. Additionally, we also got to hear some thoughts on the Charter from former President of the Canadian International Development Committee, Hugette Labelle, which she presented alongside the Museum of Ottawa, who brought in the original Charter on display. Labelle reflected on the blueprint it lays for human rights policy in Canada, and the importance of understanding it and exercising our Charter rights in order to maintain the vision for our country it lays before us.

We then heard from Natan Obed, who gave a somber detailing of the current state of isolation the Inuit people in Canada face within this country. Obed explained how a severe lack of doctors in their region makes accessing health care extremely difficult, with many people having to travel absurdly long distances and spend time on extreme waiting lists just to see doctors for simple matters. Disabled members of their community find themselves falling by the wayside in society due to the lack of support and diagnosis accessibility available to them. The cost of groceries is extremely high and unaffordable for many. He revealed that despite the resources within the Canadian government, the Inuit people continue to struggle within Canada and are left to feel disenfranchised.

This is an ongoing issue for many who live in small, isolated communities and drives a persistent migration of people into the cities. Urban areas are better able to provide resources, services, and opportunities that are scarce outside metropolitan hubs. Many Indigenous people find themselves in the devastating position of having to choose between two worlds, with many deciding to leave in favour of better education, healthcare, and career choices. As populations recede in remote areas, those who remain often see their struggles compounded with diminished support.

Conversations of this nature are important in highlighting and addressing ongoing challenges for Canadians, from medical scarcity, to food availability, to housing prices, and the answers are often not clear or straightforward. The inherent messiness of democracy is that we often do not agree on what a solution should look like, even when we can agree on the problem, but we can all generally agree that access to clean, safe drinking water is a given.

Currently, there are 34 reservations without clean drinking water in Canada. Justin Trudeau made access to clean drinking water a campaign promise in 2015, as of May 2021, the government has failed to address a third of long-term drinking water advisories. The solutions to the problem exist, but the actions of our federal government don’t reflect a strong sense of urgency in providing the necessary aid.

After the final day of presentations concluded, I climbed Parliament Hill towards a square in front of the legislative buildings. I found a spot in the park overlooking the Ottawa River and sparked up some of the ridiculously priced cannabis I’d bought upon arrival to the city. It felt strange at first, smoking weed in front of a government building. Five years ago, I would have been committing a federal crime. Now, the only thing I was guilty of was being the asshole in a public space smoking pot.

As the haze filled my lungs, I reflected on the Charter conference and the modern history we’d all unpacked together. Here I was, enjoying a freedom that my parents never had when they were young. I remember when it was legalized. There are kids today, growing up in a different world, in which it always was. For them, that freedom is a given — an expectation, like voting. Hopefully, they’ll never know otherwise.

The fact that our Charter is only 40 years old, in a country with a troubling and sordid history, demonstrates not only how far we’ve come as a nation, but also that the difficult work continues. The lofty ideals enshrined in the Charter grants our country an international reputation as inclusive, just, and free, but there are still many within our own borders who are being failed and left behind. For them, the promise of Canada is still a dream that has yet to be realized.

But progress does come, in time, if we work at it.

The Charter is many things. To those who have been historically disenfranchised, it’s a lie; for those who want to bend it to their whims, it’s a weapon; and for some who see Canada as fundamentally irredeemable, it’s a disguise — a transparent bait-and-switch in the face of institutionalized oppression. But the Charter is also a promise. It’s a reckoning; a New Year’s resolution we re-up every year. It’s a beacon to our allies, and an outrage to our foes. It’s safe harbour, and opportunity, and compassion. It says here, in this land, you can be who you are, no matter what you were. It’s an invitation to care, and to participate, and to get better. It’s a beginning, not an end.

It’s hard for me to take pride in my country. It’s difficult to look past the horrors of our past. But we have an opportunity to leverage our reputation as friendly neighbours and peacekeepers and build upon it. To practice what we preach, work for true redress and reconciliation, and raise the bar for human rights. One day, when our efforts to reach those goals match our words, that will be something to be proud of. Until then, grab your bootstraps, ‘cause we’ve got some work to do.

Kellyn Kavanagh (they/he) is a local writer, photographer, and musician. They first started writing what they now know to be flash fiction stories in the third grade when they learned how to make little books with a couple sheets of printer paper and a stapler. Their work typically focuses on non-ficiton journalism, short horror fiction, and very depressing poetry.